This post originally appeared at the Conversable Economist.

South Africa is the home for 75% of the world’s population of black rhinos and 96% of the world’s population of white rhinos. There must be some lessons for conservationists behind those statistics. Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes tells the story in “Saving African Rhinos: A Market Success Story,” written as a case study for the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC).

The story isn’t just about markets. In 1900, the white rhinoceros had been hunted almost to extinction, with about 20 remaining in a single game preserve in South Africa. The population slowly recovered a bit, and by the middle of the 20th century, there were enough to start relocating breeding groups of white rhinos to other national parks in South Africa, as well as private game ranches. In 1968, the first legal hunt of a white rhino was authorized.

But by the 1980s, Sas-Rolfes reports, a strange disjunction had emerged. In 1982, the Natal Parks Board had a list price for a white rhino of about 1,000 South African rands, but the average price paid by a hunter for a rhino trophy that year was 6,000 rands. Private game preserves were quick to take advantage of the arbitrage opportunity. The Natal Parks Board soon began auctioning its rhinos. In 1989, it was selling rhinos for 49,000 rand, but the average price to a hunter for a rhino trophy had risen to 92,000 rand. There were obvious questions about whether this system of raising and hunting rhinos was a useful tool from a broader environmental perspective.

But property rights and markets enter the story in a different way in 1991.

Before 1991, all wildlife in South Africa was treated by law as res nullius or un-owned property. To reap the benefits of ownership from a wild animal, it had to be killed, captured, or domesticated. This created an incentive to harvest, not protect, valuable wild species—meaning that even if a game rancher paid for a rhino, the rancher could not claim compensation if the rhino left his property or was killed by a poacher. . . . Recognizing the problems associated with the res nullius maxim, the commission drafted a new piece of legislation: the Theft of Game Act of 1991. This policy allowed for private ownership of any wild animal that could be identified according to certain criteria such as a brand or ear tag. The combined effect of market pricing through auctions and the creation of stronger property rights over rhinos changed the incentives of private ranchers. It now made sense to breed rhinos rather than shoot them as soon as they were received.

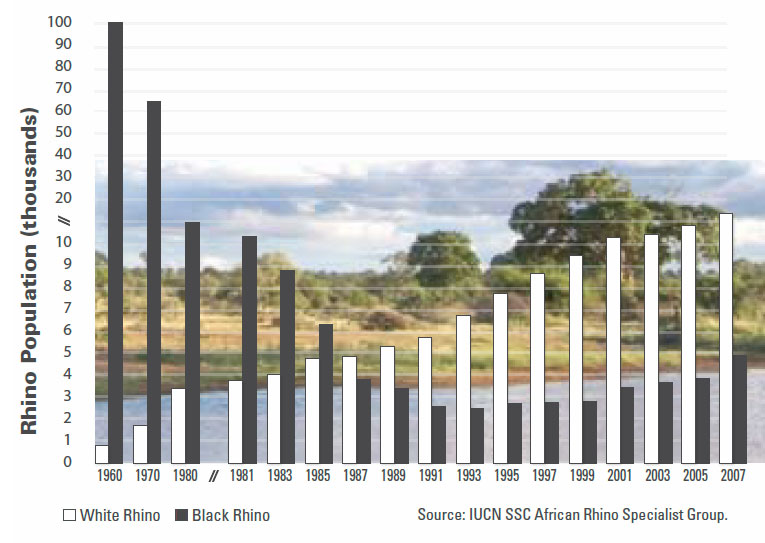

For a sense of how much difference these issues of property rights and incentives can make to conservation, consider the difference in populations between black and white rhinos. Sas-Rolfes explains: “Figure 2 shows trends in white rhino numbers from 1960 until 2007. Contrast those numbers with the black rhino, which mostly lived in African countries with weak or absent wildlife market institutions such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Zambia. In 1960, about 100,000 black rhinos roamed across Africa, but by the early 1990s poachers had reduced their numbers to less than 2,500. . . . Unprotected wild rhino populations are rare to non-existent in modern Africa. The only surviving African rhinos remain either in countries with strong wildlife market institutions (such as South Africa and Namibia) or in intensively protected zones.”

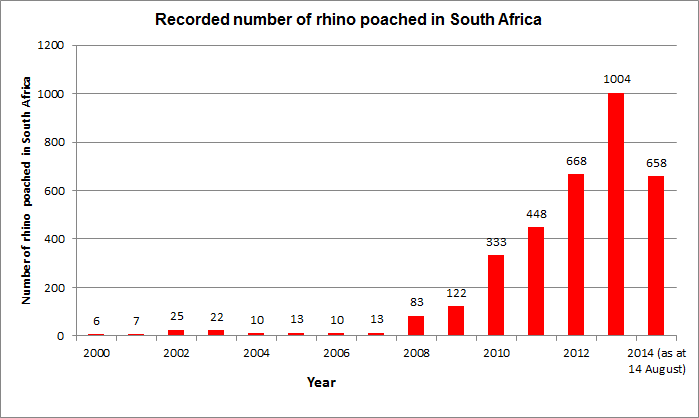

A strong demand for rhino horn remains, and especially since about 2008, rhinos across Africa face a risk of illegal poachers. Here’s a figure from the conservation group Save the Rhino showing the level of rhino poaching in South Africa:

Along with the existing choices of “intensively protected zones”–which implies costly and not-very-corruptible protectors–and allowing for private game preserves, the other option is to seek to undercut the black market for rhino horn with a legal market. Other more controversial options discussed at the Save the Rhinos website include de-horning rhinos, to make them less attractive to poachers, and perhaps even allowing legal sale of these rhino horns, to undercut the prices paid to poacher. Rhino horns are made of keratin, similar to the substance in fingernails and hair, and the horn could be removed every year or two. There are strong arguments on both sides of allowing legal sale of rhino horn: perhaps rather than undercutting the illegal market, it might also make it easier for poachers to sell their illegally obtained rhino horn. In the end, given that South Africa is now the home to most of the world’s rhinos, I suspect that South Africa will end up making the decision about whether to proceed with these options.

Those interested in how property rights might be one of the tools for helping to protect endangered species might also want to check this post on “Saving Jaguars and Elephants with Property Rights and Incentives” (December 19, 2011).