The Old West

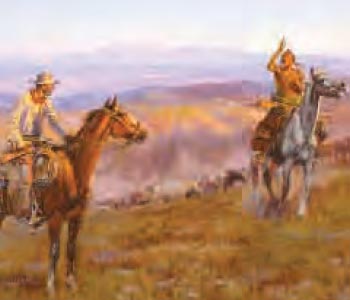

Dime store novels, Hollywood westerns, and made-for-television series such as “Into the West” have depicted the Old West as a rapacious frontier where cowboys, miners, loggers, farmers, and railroad tycoons ran roughshod over people and natural resources, with little concern for protecting the environment. Certainly, some of these images are justified. Fist fights did occur and people were shot in barroom brawls (McGrath 1984), and the Indian Wars were a shameful part of western history caused by the standing army created during the Civil War looking for a raison d’être (Anderson and McChesney 1994).

Such exciting stories, however, miss the ways in which people on the frontier hammered out the institutions—rules and customs—necessary for peaceful and productive settlement (Anderson and Hill 2004). A few examples will illustrate.

Miners from California to Montana established claims to minerals and water through the rules of the mining camps (Umbeck 1977). Because the six-shooter made nearly everyone equal in the use of force and because each claim had about the same productivity, miners honored first-possession claims as long as they were of equal size. Similarly, the prior appropriation doctrine for water rights, created in the mining camps and agricultural valleys, remains the basis for water law throughout the American West.

On the grazing frontier, cattlemen established property rights to land by posting notice on signs or in local newspapers that they had claimed land. These rights, enforced by the cattlemen’s associations, could be traded.

These property institutions provided secure and transferable ownership, which encouraged efficient resource use. As demands changed, people could change uses through voluntary exchange. The prior appropriation doctrine for water, for example, allowed water transfers from one diversion use to another.

Decline of the Old West

The arrival of formal government, however, changed decision making in the West. Of course, government can and did play a positive role by reducing the costs of defining, enforcing, and trading property rights. For example, once cattlemen established branding as a way of identifying their cattle, they turned to territorial and state governments to register and enforce their brands.

But the farther that decisions are removed from owners and from local constituencies, the more likely interest groups are to find ways to shift the costs to others while capturing the benefits for themselves. When the federal government set aside millions of acres as public lands, they were initially managed at the local level, and management even bordered on privatization because specific individuals or groups were virtual owners. For example, Yellowstone National Park (like other national parks) was de facto owned by a railroad (Anderson and Hill 1996).

Today, however, federal agencies such as the Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the Bureau of Land Management control nearly one-third of the nation’s land. On these lands, use is allocated through political and bureaucratic processes.

The history of Yellowstone Park tells the story of this transition. In the late 1860s the Northern Pacific Railroad recognized the value of Yellowstone’s unique amenities for potential passenger traffic. But homesteaders were already trying to establish claims to sites such as Mammoth Hot Springs and Old Faithful. Having no way to establish private ownership of the entire area, the Northern Pacific lobbied Congress to set aside Yellowstone as a national park and close it to homesteading. By controlling services such as railroad transportation to Yellowstone and stagecoach travel and services within the park, the railroad became a virtual owner—with an incentive to preserve Yellowstone’s unique features.

After other railroads arrived and the park was opened to automobiles, the National Park Service took over. But during its early years, the National Park Service too acted like an owner, obtaining enough revenue to fully cover its costs and then some.

More recently, the National Park Service has become a political football. Jockeying is rife over issues such as adding wilderness, building campgrounds, allowing snowmobiles, and reintroducing species such as wolves. Each issue represents a competing demand and requires the National Park Service to reallocate the resources under its charge.

The U.S. Forest Service provides a similar story. Initially, the Forest Service had one constituency, loggers. When grazing was added as a commodity on Forest Service lands, there was no significant conflict between the two demands. More clearcuts meant more grass.

Since World War II, however, Forest Service lands have become a recreational playground—and a bureaucratic battleground. Not only do hiking and backpacking conflict with logging, but recreation itself is riddled with dissension as snowmobilers compete with skiers and all-terrain vehicle users compete with wilderness campers, hikers, and backpackers.

In the past, the Bureau of Land Management relied on local grazing districts run by committees of local ranchers. In recent years, amenity demanders have battled to rein in grazing in the interest of increasing wilderness, wildlife, and recreation.

With water, too, bureaucracy overtook private ownership. By building dams and delivery systems, the federal government supplanted private irrigation development (Anderson and Hill 2004) with massive subsidies to farmers (Rucker and Fishback 1983). As long as the reclamation projects were primarily for irrigation and secondarily for hydro-electric production, conflicts were few. But in recent years pressure to preserve endangered species and other wildlife has increased.

In the Klamath River basin in Oregon,2 environmentalists, bolstered by Indian tribes whose treaties give them hunting and fishing rights, demanded that water be left in the river for threatened or endangered fish species. In the spring of 2001, the Bureau of Reclamation shut off water to farmers, instigating a bitter fight that continues during drought years. Who has the right to the water? Farmers who have prior appropriation rights or contracts with the Bureau of Reclamation? Indian tribes who have treaty rights for fishing and hunting? Or environmentalists who claim water for endangered fish?

New West Meets Old West

In the past, people could exchange their private property rights to land, water, and minerals to accommodate different values while prompting higher valued uses. In contrast, politics generally substitutes one use for another—in a zero-sum game. Not surprisingly, federal agencies and even some state agencies find themselves locked in political or court battles over virtually every decision they make.

Because privatization is not feasible today, at least we may be able to devolve decision making to levels where the participants have a greater stake in the outcome, as well as have more knowledge about the resources. Here are proposed changes in three areas:

Land

Those who graze cattle on federal lands have relatively secure property rights to their grazing permits (Nelson 1996), although this security has been waning. To accommodate the new demanders—primarily environmentalists who want to reduce livestock grazing—a simple solution is to make existing permits transferable to non-grazers on a willing buyer-willing seller basis. The Grand Canyon Trust and the Conservation Fund have been trying to do this in southern Utah. But federal regulations make such trades difficult, if not impossible.

Devolution could improve timber management, too. A decade ago, PERC Senior Fellow Donald Leal (1995) made side-by-side comparisons of federal and state forest management in Montana. He found that while federal forests on average lost 50 cents on every dollar they spent, state forests made $2 for every dollar they spent. Moreover, state forests produced more environmental amenities such as clean water and wildlife habitat.

The difference between the two was the management incentives. Federal forest managers obtain most of their funds through congressional appropriations and mostly send their revenues to the federal treasury. State forests are required to earn a profit for the school trust, which is carefully monitored by teachers, administrators, and parents. To earn profits, they will consider recreation, scenery, and other amenity values as assets that may outweigh the value of timber production.

Water

Rather than having agencies and legislators in Washington, D.C., trying to cure the problems of the Klamath, local people could and are addressing them through trading. Throughout the West, allowing environmental interests to lease, purchase, or leave water instream is an important step toward resolving disputes between irrigators and environmentalists.3 Groups such as the Oregon Water Trust, Washington Water Trust, and Montana Water Trust are filling this niche of voluntary, nonconfrontational water trades for environmental goals.

Wildlife

Wolves were successfully introduced into Yellowstone National Park because an environmental group, Defenders of Wildlife, decided to compensate livestock owners for losses caused by wolves (Fischer 2001). Defenders raised private funds to establish a fund for compensating livestock owners for livestock killed by wolves. Defenders acted like an owner— taking on liability for predations and bearing a share of the cost of wolf reintroduction.

Leasing or purchasing land for wildlife habitat is another example of how markets can shift uses from traditional commodities to higher-valued amenities. Non-profit groups, clubs, associations, and for-profit firms can and do broker such transactions.

Conclusion

In the New West, where political institutions control the allocation of many natural resources, conflict is inevitable. But recognizing existing property rights—whether they be private, as with land, or political, as with grazing permits—and encouraging exchange can link the New West with its Old West heritage. Markets for conservation easements, grazing permits, water rights, and hunting habitat are evolving. State management of land and parks is less contentious and more economically and environmentally sound than federal management. Water markets reduce acrimony and encourage incremental solutions that shift water from traditional uses to recreational and amenity uses. Conservation easements provide open space and other amenities. Private ownership and devolution of governmental control, features of the Old West, offer the best hope for the future of the New West’s natural bounty.

NOTES

- Sometimes the new amenity demands are couched in terms of ecosystems and biodiversity, but regardless of the terms used, they are human demands articulated by human beings.

- For a discussion of the conflicts over instream and off-stream water uses on the Klamath, see Meiners and Kosnik (2003).

- For a complete discussion, see Anderson and Snyder (1995) and Landry (1998).

REFERENCES

Anderson, Terry L., and P. J. Hill. 1996. Appropriable Rents from Yellowstone: A Case of Incomplete Contracting. Economic Inquiry 34 (July): 506–18.

———. 2004. The Not So Wild, Wild West: Property Rights on the Frontier. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Anderson, Terry L., and Fred McChesney. 1994. Raid or Trade? An Economic Model of Indian–White Relations. Journal of Law and Economics 37 (April):

39–74.

Donald R. Leal is a senior associate of PERC and editor of Evolving Property Rights in Marine Fisheries (Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), among other books.

Anderson, Terry L., and Pamela A. Snyder. 1995. Water Markets: Priming the Invisible Pump. Washington, DC: Cato Institute.

Fischer, Hank. 2001. Who Pays for Wolves? PERC Reports, December. Landry, Clay J. 1998. Saving Our Streams through Water Markets: A Practical Guide. Bozeman, MT: PERC.

Leal, Donald R. 1995. Turning a Profit on Public Forests. PERC Policy Series, PS-4. Bozeman, MT: PERC.

McGrath, Roger D. 1984. Gunfighters, Highwaymen, and Vigilantes: Violence on the Frontier. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Meiners, Roger E., and Lea-Rachel Kosnik. 2003. Restoring Harmony in the Klamath Basin. PERC Policy Series, PS-27. Bozeman, MT: PERC.

Nelson, Robert H. 1996. Public Lands and Private Rights: The Failure of Scientific Management. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Rucker, Randall R., and Price V. Fishback. 1983. The Federal Reclamation Program: An Analysis of Rent Seeking Behavior. In Water Rights: Scarce Resource

Allocation, Bureaucracy, and the Environment, ed. Terry L. Anderson.

San Francisco: Pacific Institute for Public Policy Research, 45-81.

Umbeck, John R. 1977. A Theory of Contract Choice and the California Gold Rush. Journal of Law and Economics 20(2): 421–37.