When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark wintered in 1804–05 among the Mandans and the Hidatsas in what is today North Dakota, they also traded. Fabricating iron implements at their portable forge, they bartered them for the corn and squash that sustained the Corps of Discovery through the bitterly cold winter. A few months and a thousand miles later, Lewis was astonished to arrive in the Nez Perce community and ï¬nd that one of these trade axes had proceeded him.

By contrast, an earlier, nearly fatal encounter with the Teton Sioux was a result of Lewis’s brash announcement that the United States would now be taking charge of commerce. Incensed, the Tetons threatened to eradicate this intrusion upon the ï¬nely tuned regional trade network. By that harsh lesson, Lewis learned to approach the local trade czars with deference and diplomacy. Ultimately, Lewis and Clark reported to President Thomas Jefferson that native inhabitants throughout the Louisiana Territory were a thoroughly independent, businesslike lot—sharp entrepreneurs and shrewd dealers.

The point to be extracted is that American Indians never have been strangers to the American entrepreneurial spirit. The point to be projected from here forward is that contemporary American Indian sovereignty depends upon a successful rekindling of that entrepreneurial spirit. It’s the Indian way.

BEYOND POLITICAL SOVEREIGNTY

In 1971 the late Alvin Josephy, along with a host of leading thinkers, declared a new paradigm for American Indians: self-determination. Josephy deï¬ned the concept as “the right of Indians to decide programs and policies for themselves, to manage their own afirs, to govern themselves, and to control their land and its resources” (1971). The announcement gave structure and shape to the policy evolution that has occupied the Indian debate for the ensuing thirty-ï¬ve years. Progress toward that vision has been substantial.

As a concept, tribal self-determination has been elevated to the status of something called “tribal sovereignty.”1 This is self-government by Indian tribes as delineated by court cases Huge credit is due to the warriors for tribal sovereignty. But the paradigm has an obvious shortcoming: It lacks consideration for the role of the Indian citizen, the individual, the person.

Even with tribal sovereignty, we continue to experience devastating personal and family-level despair. Poverty and unemployment are twice the national average; we have consistently lower educational success than the national norm; alcohol-related mortality rates are triple the national average (Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development 2004). We should think of these human imperatives as matters of Indian sovereignty as distinct from tribal sovereignty.

Indian sovereignty—the autonomy of the Indian person— means re-equipping Indian people with the dignity of self-sufï¬ciency, the right not to depend upon the white man, the government, or even the tribe. This is not a new notion. It is only a circling back to the ancient and most crucial of Indian values— an understanding that the power of the tribal community is founded upon the collective energy of strong, self-suffcient, selfinitiating, entrepreneurial, independent, healthful, and therefore powerful, individual persons. Human beings. Indians.

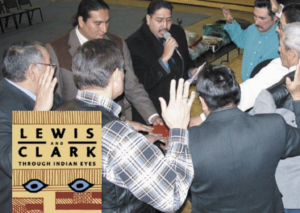

Even a cursory review of our revered traditions, stories, and legends reveals a recurring celebration of the man or woman who is distinguished for empathy with and generosity Tribal self-government, illustrated by this 2004 swearing-in of members of the Crow legislative branch in Montana, is important. But so is the autonomy of the individual Indian. had to have been resourceful and capable enough to generate wealth in the ï¬ rst place. Call it enterprise or entrepreneurship or productive capability, it is the underlying assumption of the legend. Th at is the Indian way. It always has been.

SOMETHING IS AWRY

This is is not to diminish the reality of forces of oppression and injustice: displacement, incarceration, forced dependency, impoverishment, and human trauma of the worst kinds. The bicentennial observance of the Corps of Discovery evokes bitter memories of injustice and tragedy. But as Amy Mossett, Hidatsa-Mandan historian, states, we must move on. “Our tribes have survived catastrophic events in the past 200 years. But if we grieve forever, we will never move forward” (quoted in Time Magazine, July 2, 2002).

Between the time of Lewis and Clark and today, something has gone awry with our proud and powerful Indian myth (I use that term to mean our sense of who we are and how we ï¬ t in the universe; that is, our self-actualizing identity). A destructive dissonance has arisen between our most revered cultural standards and our day-to-day, operational culture

Our operational culture is slashed by personal and community despondency. Dependency has become the reality of our daily existence. Worst of all, generation by generation it becomes what sociologists term learned helplessness—an internalized sense of no personal possibility, transmitted he- reditarily and reinforced by recurring circumstances of hopelessness. The manifestations are epidemic: substance abuse, violence, depression, crime, trash.

The danger for Indians lies in capitulation to victimhood as an acceptable community myth. Excuse-making and blame provide shelter for irresponsibility, incompetence and failure of personal initiative.

Michael Running Wolf, a Northern Cheyenne, admonishes us Indians and the community at large to beware the victimhood myth: “[W]e walk the border between protecting our values, and acting the part of victim. Not victims in the sense of being injured individuals, but subscribing to the belief that we deserve sympathy. It’s belief that bases our identity upon the wrongs we have endured, rather than our accomplishments and integrity. It’s a phenomenon that demands the nurturing of victimhood” (Letter, Bozeman Daily Chronicle, Nov. 2, 2004).

Running Wolf is right. There is no future in victimhood and its self-destructive corollaries—excuses and dependency. Far better to apply our ï¬nite personal energy to a constructive belief system and a corresponding action plan.

Huge credit is due to the

warriors for tribal sovereignty.

But the paradigm has an

obvious shortcoming: It lacks

consideration for the role of the

Indian citizen, the individual,

the person.

Every Indian community will have to make a determined effort to confront our realities, analyze our conditions and our prospects with all of the tools of modern social science, and then chart a strategic course back to individual and community strength. For example, it is time to move beyond training only teachers, lawyers, and petroleum engineers Far better to apply our ï¬nite personal energy to a constructive belief system and a corresponding action plan. Every Indian community will have to make a determined effort to confront our realities, analyze our conditions and our prospects with all of the tools of modern social science, and then chart a strategic course back to individual and community strength. For example, it is time to move beyond training only teachers, lawyers, and petroleum engineers and begin preparing some smart, energetic, and dedicated Indian sociologists, psychologists, geographers, economists, and MBAs. These professionals, in tandem with our elders, can help us understand the human dynamics of where we are and help us identify the insertion points for us to intervene in our cycle of despair and dependency.

“It is not Indian to fail!” Birdena Realbird, a Crow public-school educator and irrefutable traditionalist in her own right, asserts that excuse-making serves no constructive end. To say that Indians cannot be expected to excel in the contemporary universe because of our Indian-ness is the worst kind of insult to the honor of our proud culture and blood heritage. Rather, argues Realbird, we ought to view ourselves as fortiï¬ed by our heritage and therefore better equipped than most other folks to prevail over whatever challenge arises.2

Personal accomplishment follows robust expectations, and vital community psychology follows both. Now, that is a myth to evolve to—or return to. That is the Indian way as it was before Lewis and Clark.

RETHINKING TRIBAL GOVERNMENT

Tribal sovereignty—that is, the prerogative of governing territory and the interactions among the people in the territory —is a necessary government purpose. That is why we have such a lively economy in the Indian law world, even when the rest of the regular Indians flounder in poverty: A disproportionate share of tribal ï¬nancial resources is absorbed by legal costs of endless (but admittedly necessary) litigation over issues of tribal sovereignty. Those resources, or at least some of them, could well be dedicated to meaningful economic development.

The trouble is that we Indians are so focused in tribal-think and on tribal jurisdiction, which by deï¬nition entails power, control and influence, that we completely overlook the daily exigencies of Indian living.

Secondarily, tribal governments try hard to rescue the people by “program.” Comparatively little of the tribal government energy and budget typically go to empowering people toward sustainable self-suffciency.

The tribe has a critical function in the arenas that government can do well. But even at its most benign, tribal government has failed to grasp what virtually all other institutions in the world know—that government is inherently poorly suited to being in business. The proper economic role for tribal government ought to be to ensure necessary infrastructure and then facilitate private enterprise for Indian entrepreneurs, with an eye toward building the capacity of individuals and families to be truly independent.

Economists Stephen Cornell and Joseph Kalt (1998) of Harvard University point out the prerequisites for sustainable entrepreneurship in Indian communities: stable institutions and policies; fair and effective dispute resolution; separation of politics from business management; a competent bureaucracy; and cultural coherence. “The central problem is to create an environment in which investors—whether tribal members or outsiders—feel secure, and therefore are willing to put energy, time, and capital into the tribal economy”(Kalt 1996).

THE “NOT-INDIAN” FALLACY

Surely, some of the enormous intelligence, resourcefulness and creativity ensconced in the tribal official/tribal attorney reservoir could be redirected to making this happen. Yet two standard objections to the creation of entrepreneurial institutions are predictable.

First, “it’s not-Indian” to be in business. But this is simply mistaken. To believe it would guarantee self-defeat, given the global socio-political-economic milieu, driven by proï¬t, in which we exist. Furthermore, we all know a few hardy Indian souls who are making it on their own.

The second objection is that individual enterprise contradicts our Indian sense of and commitment to the welfare of the whole, the tribe. Of course, our ancient ethic of the interdependence of all people and all things is one of the gifts that we Indians can offer Western philosophy whenever our neighbors are at last willing to acknowledge it. We treasure the sense of kinship and community that has always been key to our survival.

But, as noted above, the wherewithal for generosity and sharing must originate in initiative, enterprise, and creativity on somebody’s part. That is neither selï¬sh nor greedy; it is simply being resourceful and capable, perhaps motivated by a desire to be altruistic and generous.

“You’ve got to take care of yourself, and then you can take care of your family and your community,” says Shane Doyle, a young graduate student who is a singer from a traditional Crow family.3 To buy into the opposite thinking is to kill personal motivation and, ultimately, buy back into the deadly dynamics that got us in this ï¬x in the ï¬rst place.

What endures, and shall always sustain us if we choose to pursue it, is our strength, our uniqueness, our conï¬dence as Indians. Within that framework of profound spiritual commitment, our cultures have always evolved on a multitude of fronts—religious, material, linguistic, economic, artistic, intellectual. But too often today, we ï¬nd it tempting to time-freeze our myth, usually in an era already past, and then enforce it with a posse of culture police.

SEIZING OUR DESTINY

Increasingly, however, we feel a dissonance between our traditional culture, which tends to be reserved for periodic celebrations, and our daily operational culture. We cannot affrd to allow that gap to expand into a gulf. Indian communities must be visionary enough to give our people permission to evolve our culture so that it is relevant to our personal existence.

A linchpin of this is economic security on a purely personal Indian basis. We don’t need much, but we cannot function in today’s world without economic dignity. If we can achieve that, then we can free our creative energies for the greater works of community vitality and tribal sovereignty. We must give Indians permission to pursue that age-old but newly-remembered paradigm of entrepreneurial self-suffciency. Surely that is not the entire solution, but it is part of the puzzle.

We trust that if we empower our people to seize their own Indian destinies then they will take care of our tribal destiny. That is the Indian way.

Cornell, Stephen, and Joseph P. Kalt. 1998. Sovereignty and Nation-Building: The Development Challenge in Indian Country Today. Cambridge, MA: The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development.

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development. 2004. Fact Sheet: Key Statistics about Native America, September.

Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. 1971. Red Power: The American Indians’ Fight for Freedom. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kalt, Joseph P. 1996. Statement before the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, September 17, 1996.

NOTES

1. The phrase “tribal sovereignty” should be purged and replaced because it conjures up unrealistic expectations and grounds for an unnecessary ï¬st- ï¬ght all around.

2. Personal conversation, 2004.

3. Personal conversation, 2004.

BILL YELLOWTAIL is a senior project specialist with the Cook Center for Sustainable Agriculture, a former Montana state legislator, and a member of the Crow Tribe. This article is excerpted from Lewis and Clark through Indian Eyes, edited by Alvin M. Josephy. It is published in arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.