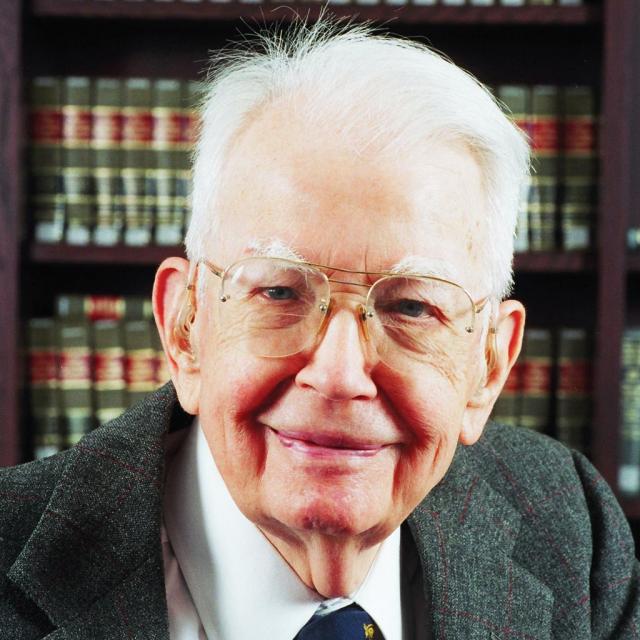

Born in Willesden in 1910, Coase spent much of his career in the US, winning the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1991. His fame rested on two papers. The first, in 1937, explained why companies exist — islands of central planning in a sea of market negotiation. His answer was “transaction costs”: you could order a car from the suppliers of its many parts, but it’s a lot simpler to get Henry Ford to assemble it for you.

Not only do companies lower the cost of goods by co-ordinating production, they depend on having a reputation for doing so. You cannot know all the suppliers with whom you might deal, let alone if they can be trusted. Firms such as Amazon spring up to save us these transaction costs.

Companies also face transaction costs: for renting buildings, employing accountants and managers and so on. Coase taught us that the ideal size of a company will be set by the interplay of lower co-ordination costs through central planning and higher transaction costs associated with holding managers accountable.

This is a penetrating insight for markets and government. Steam and electricity, by making production lines possible, lowered co-ordination costs, making bigger firms viable. But bigger companies, like bigger government bureaucracies, have higher management costs. The difference, of course, is that profits in the marketplace signal whether firms are too big or too small.

Coase’s second famous paper, The Problem of Social Cost, published in 1960, was also about transaction costs. It was written after an argumentative evening in Chicago, when he changed the minds of 21 economists, including Milton Friedman, over whether radio frequencies could be bought and sold rather than allocated by government.

Coase’s insight has a more general application to environmental issues. In a dispute between (say) two people in Sussex, one of whom wants to drill for oil, while the other wants a pretty view, Coase explained that in a costless world, the winner could best be determined by negotiation, not regulation. If A values the view more than B values the oil, let A buy out B.

Coase recognised that such transactions were not costless, but used his legal training to show how courts clarify rights and thereby lower transaction costs. But he did not see markets as a panacea. A world of zero transaction costs is as unattainable as a true vacuum in physics. In both, however, the question is how much difference do transaction costs (or air pressure) make in the real world.

Coase always focused on the institutional setting, asking how markets compare with governmental regulations. Neither is perfect. Government regulation, too, has transaction costs: enforcement and monitoring, corruption, inefficiency and resistance to innovation. Just as Coase dragged economists away from assuming perfect competition, so he tried — and largely failed — to drag them away from assuming perfect government with perfect knowledge.

Consider pollution by an airport, a nuisance effectively nationalised by the State. A resident of Hounslow cannot sue Heathrow for disturbing his sleep because the Government has decreed that airlines may make a certain amount of noise at certain times while using the airport. That robs the Hounslow resident of something of value. Had he been able to negotiate with Heathrow, he might have demanded less noise, or might have settled for even more noise so long as he was well compensated.

But government restrictions on night flying and on building a third runway steal something from a resident of Edinburgh, too, by insisting he circle uncompensated over Buckinghamshire every time he flies to Heathrow. Surely there is a possible deal here. But transactions costs might get so complicated — one Hounslow resident holds out for more or one Edinburgh resident refuses to pay — that government regulation may be less trouble than a noise market. Coase, always the pragmatist, said it depends on the circumstances.

Lest you think environmental markets are scarcer than hen’s teeth, consider that a US charity called the Nature Conservancy has purchased fishing rights off California to reduce the impact of trawling on marine ecosystems. A think-tank in Bozeman, Montana, called PERC, seeks out such solutions created by what it calls “enviropreneurs”. It has found many cases of conservation organisations doing deals with oil drillers to the benefit of both, or buying water rights off farmers to help fish — all without any government regulation. Terry Anderson, president of PERC, thanks Coase “for giving us the intellectual foundation on which free market environmentalism is built”.

Coase constantly reminded us that economics is in the business of explaining how people actually behave, not telling then how to behave.

Article and comments at The Times.