Last January, California Governor Jerry Brown declared a State of Emergency following projections of severe drought. State bureaucrats and local officials jumped into action and mandated any number of water conservation tactics. While some have been relatively successful, most will do nothing. In fact, it appears that despite the drought, water use may have actually increased in the past year.

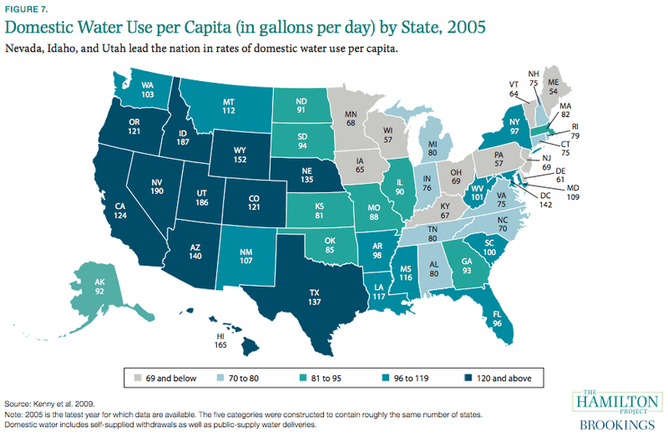

So, exactly how much do Californians value their decreasing supply of drinkable water? According to the California Water Service Company, it is valued at less than a penny per gallon. If water were plentiful, an almost-zero price would not be a problem, but under the current situation it is truly a catastrophe. The average American uses 100 gallons per day, Californians average 124, and in some regions of California up to 379 gallons per person per day. That sounds a bit outrageous for a state experiencing a drought of Biblical-plague proportions, doesn’t it?

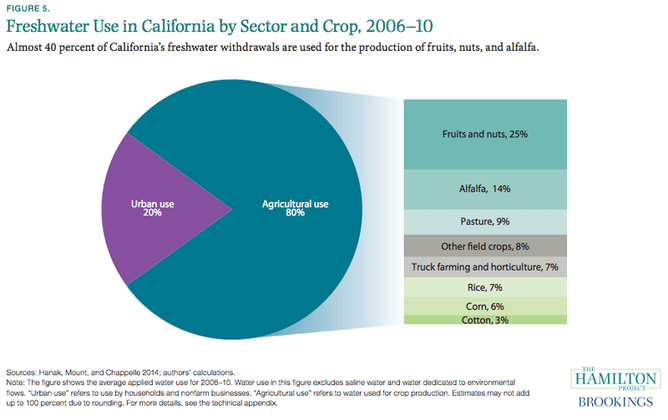

The solution to rectifying California’s abysmal water conservation record might be found in California’s agricultural sector. In just the past year, prices for irrigation water have risen from ten to almost forty times last year’s price. Those who have the water to spare can make a sizable profit by selling it to those who need it. Thus, because the value of water has significantly increased, every gallon is a precious commodity that is not wasted.

Allowing price to ration water may be a bitter political pill to swallow, but it makes economic and environmental sense. There are examples of this economic solution working in the past. Cities like Santa Fe, Tucson and Fort Worth allowed price signals to govern water use – the more a household used, the more expensive water was to purchase. Consumers responded by conserving water. These measures worked so well utilities were forced to stabilize the sharp drop in revenue by reconfiguring rates. That is not a bad thing – especially during a drought as austere as California’s.

But won’t raising prices only hurt the poor and have little effect on those who have the money to afford it anyways?

Charging more for water need not create undue hardship for poor or lower middle class families. Establish a minimal per capita water use level and then charge progressive water rates so that any extra water used is billed at a higher rate. This allows consumers to choose if they are willing to pay for an extra long shower, to water their lawn or to wash their car.

This solution would not even require much change in the way water is already billed. Typically, water usage is billed at three tiers of usage. For example, in Bakersfield, the price of water is as follows: US$1.66 per 100 cubic feet of water for the first 1,300 cubic feet used, US$1.80 per 100 cubic feet of water for the next 2,100 cubic feet used, and US$2.09 for every 100 cubic feet of water used after that (a cubic foot of water is roughly 7.48 gallons).

That’s only a difference of 43 cents from the basic rate to the charge for unlimited use. Why not increase the price of the second and third tiers by a dollar – or two or three for that matter? Doing so would have little effect on a family that expends the effort to conserve.

Take an average family of four, each using 100 gallons of water per person per day. Over the course of a month this family would use about 1,600 cubic feet of water. The first tier could be raised to 1,600 cubic feet and the second and third tiers adjusted accordingly. A simple adjustment of the water bill would ensure that any family, regardless of economic status, would be able to afford a comfortable level of water while being charged for any water usage above and beyond that base amount. This approach is fair to those struggling financially, but it also puts pressure on everyone to conserve a scarce resource.

Raise the price of water. Signal to consumers that it is a valuable and precious resource. Let consumers make their own decisions on how they allocate their resources in using, or conserving, water.

Originally appeared in The Conversation on November 7, 2014.

Michael Jensen, a policy analyst at Strata Policy, contributed to this article.