This special issue of PERC Reports explores the West’s water crisis and how markets can address today’s shortages. Read the full issue.

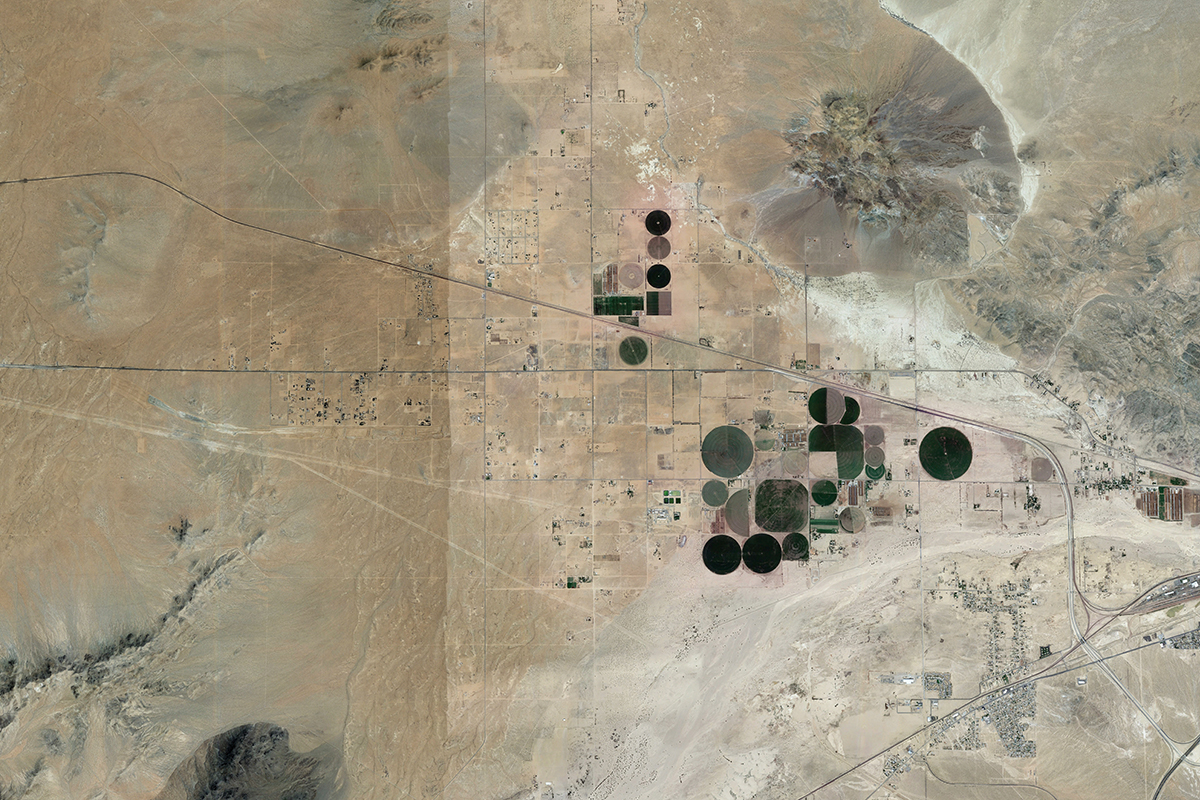

California’s Mojave Desert has long been home to productive agricultural operations and growing communities. Located northeast of Los Angeles, the area is also host to dairies, solar installations, man-made recreational lakes, and unique habitats. One thing lives and livelihoods in the area have in common is their dependence on groundwater, a resource that is in short supply in North America’s driest desert.

Residents struggled for many years with how best to manage water scarcity, but today the Mojave is home to one of the most liquid groundwater markets in the western United States. Introducing this system stabilized water levels in the area and generated significant economic benefits for local communities. The story of its development and operation offers lessons to other basins in California and across the West.

Access to groundwater in the Mojave is now managed to ensure pumpers do not deplete underground aquifers, and the long-term prospects for resource users are promising. But this was not always the case.

Forging the Mojave Agreement

As in much of California, groundwater in the Mojave’s aquifers was historically available to virtually anyone who could access and pump it to the surface. That included overlying landowners for use on their lands, but other parties, such as cities, could also establish rights to groundwater for other uses. Only small amounts of water, however, seep from the Mojave’s dry, desert surface into aquifers each year to refill them, a process known as recharge. Most natural recharge is provided by seepage from the Mojave River as it flows north from the San Bernardino Mountains, as well as the small amount of precipitation that falls in the desert.

Throughout the 20th century, increased groundwater extraction—in large part for agriculture, and enabled by advances in pumping technology—unbalanced the aquifer system. Pumping rates began to exceed the reliable recharge of aquifers. As water tables fell, pumping costs rose and concerns about long-term storage and water availability grew. Average water table heights fell by 30 feet from the early 1900s to the end of the 1950s, and similar declines occurred through the end of the 1980s. In some areas, declines were even greater. Other impacts emerged, such as subsidence of the land surface.

In response, local governments and concerned users started early discussions around a solution, which focused on augmenting water supply. In the late 1950s, the state embarked on its efforts to build the State Water Project—a system of dams, canals, and other infrastructure that captures water in the wetter north and conveys it to the drier south—and local users worked with state legislators to form the Mojave Water Agency to contract for water from the project. The agency would use the project water to recharge the aquifer. Given the high cost of water delivered through these contracts, the agency attempted to delineate by volume the groundwater rights of individual pumpers to constrain overuse of both native basin water and imported water. In addition to improving groundwater conditions, a major goal of this effort was to assign responsibility for paying for imported water. Over the years, a proposal for a court process to adjudicate water rights and alternative proposals for pumping taxes were all met with controversy and ultimately unsuccessful. Overdraft of the region’s aquifer system persisted.

It was not until 1990 that a successful adjudication of the region’s groundwater began. A lawsuit filed by one growing municipality alleged that overpumping by other users would constrain its future access to groundwater. The Mojave Water Agency joined the process and prompted the court to consider the unsustainable pumping as well as the nature of water rights in the basin more broadly. By 1996, Mojave’s groundwater pumpers had negotiated a settlement that set total limits on extraction and allocated pumping rights to individual users and municipalities.

The Mojave’s adjudication of its groundwater rights represented an effort to both constrain overuse of the region’s native natural resources and establish an incentive to conserve expensive imported water. Without a way to control pumping, users could continue or even expand extraction, relying on but not directly paying for the imported water. To address this, the new system included individual entitlements for large pumpers—with fees for exceeding them linked to the cost of imported water—and exemptions for small pumpers. It also established pumping fees to fund additional agency activities. The system generated significant changes, leading to reductions in baseline pumping of more than 50 percent in some areas, helping to stabilize water levels.

The Mojave is now home to one of the most liquid groundwater markets in the western United States.

Earlier cases in Southern California had paved the way for users to reconcile competing claims and define volumetric entitlements. But the Mojave agreement was one of the first to lay out clear foundational rules for trading pumping rights, setting the stage for what is today one of the most active groundwater markets in the western United States. Because the degree of necessary cutbacks in the Mojave was quite large, allowing flexibility for water users to reallocate resources to high-value uses was important. In large part, this has involved agricultural users leasing and selling pumping entitlements to cities. Some cities in the region have experienced double-digit growth rates decade after decade. Recent research has estimated the economic benefits of trading for the region (see text box below), and gains for individual landowners played a role in generating support for the new management structure.

Interest in groundwater allocation systems of this sort has grown in response to California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, adopted in 2014. This legislation requires groundwater users in other overdrafted basins throughout the state to achieve sustainable management by 2040. In some of these basins, absent a significant expansion in recharge, pumpers can expect cutbacks similar to those in the Mojave. For example, in Southern California’s Borrego Springs, some estimates suggest reductions of roughly 75 percent may be needed to stabilize water tables.

Three aspects of the Mojave experience show that setting up a successful management system is about more than just capping the use of a proverbial bathtub of water. First, there are hydrologic realities that need to be taken into account. Second, market systems can prompt useful adjustments by users. Finally, regulators may need to adapt over time to ensure the integrity of the system.

Going with the Flow

Most aquifers are not bathtubs. They may have areas of greater and lesser recharge, varying subsurface flow rates, upstream and downstream sections, and fault lines that buffer some areas from others, among other unique characteristics. As groundwater users contemplate how to address aquifer depletion, these factors require additional consideration beyond simply capping individual users and metering their use.

The city of Barstow, California, is a desert outpost with approximately 25,000 residents and lies along the Mojave River roughly in the center of the basin’s adjudicated area. It also lies downstream of some larger water users nearer the San Bernardino Mountains. Due to physical constraints in the flow of water from this upstream area to the city, its section of the aquifer may receive less recharge if water levels in the upstream area decline substantially.

The market gives water an opportunity cost, which is reflected in the price of pumping permits. Conservation becomes a tool with a payoff, coordinated by the market.

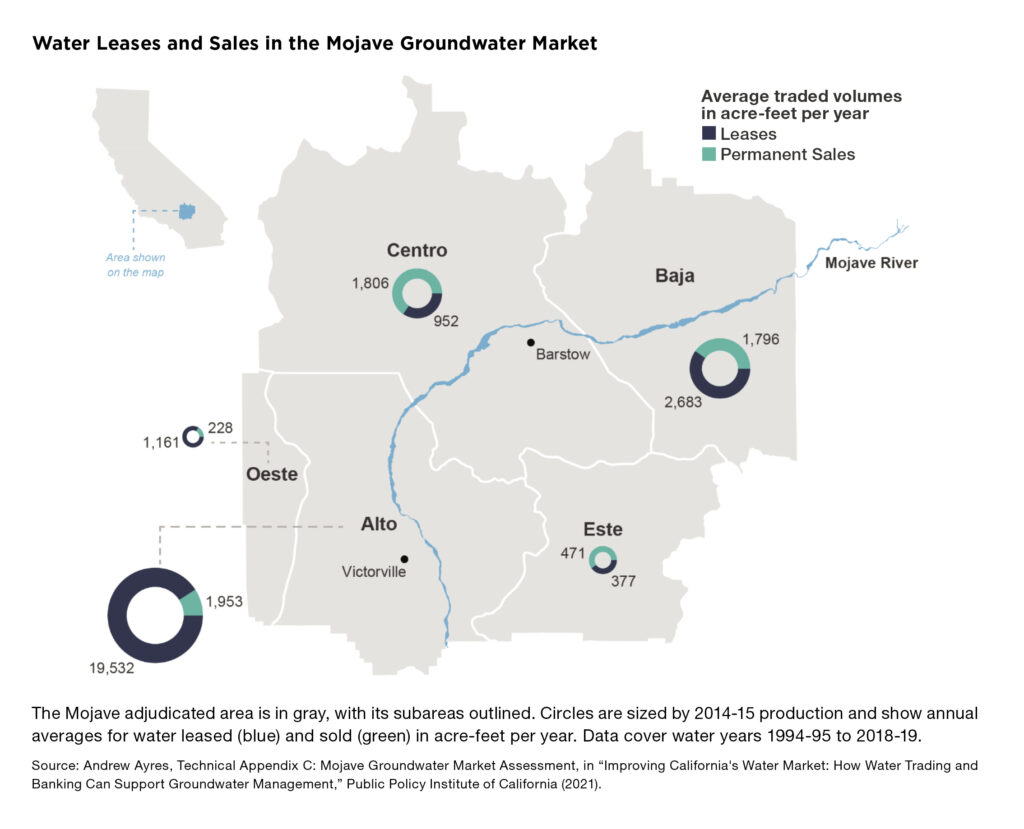

The city’s concerns about flow—both surface and subsurface—to its segment of the basin prompted the 1990 lawsuit that spurred the region’s groundwater adjudication. Barstow’s complaint focused on ensuring sufficient flows between upstream and downstream sections of the aquifer. Taking this concern seriously meant defining subareas of the aquifer to govern basin management decisions. The 1996 agreement defined annual flow obligations between subareas to ensure that any changes in pumping in one subarea that might impact water levels in another are addressed.

Today, flows across these boundaries are estimated by the Mojave Water Agency and, in the event flows fall below negotiated thresholds, users in the upstream area must make up the shortfall for the downstream subarea. Planning around these basin idiosyncrasies was ultimately necessary to effectively address users’ concerns about water availability.

An Underground Market

In addition to playing an important role in the formation of the new management system, the city of Barstow has also been an active participant in Mojave’s market for pumping permits. Capping individual and aggregate extraction helped improve groundwater levels throughout the basin. But the market helps to ensure that these goals are met at lower cost by allowing users to flexibly adapt to increasing scarcity. The market gives water an opportunity cost, which is reflected in the price of pumping permits. Conservation becomes a tool with a payoff, coordinated by the market.

Every year in the Mojave upwards of 20,000 acre-feet of water are leased across all subareas. These leases represent a temporary reallocation of the right to pump groundwater from one user to another. Public water supply systems are typically buyers, and much of this transferred water originates in agriculture, but not all of it does. Barstow’s water use and marketing activity, for example, has shifted substantially over time.

Early on in the new management regime, Barstow’s water purveyor pumped approximately 8,000 acre-feet of water annually to meet public supply in its service territory. Since then, conservation efforts have reduced annual pumping to roughly 5,000 acre-feet per year—all while the population in the city has remained relatively unchanged. Over the same period, leased amounts from the city’s system operator to other pumpers have increased from almost nothing to roughly 3,000 acre-feet on average. In the span of roughly two decades, the city that kicked off a basin-wide groundwater adjudication by suing its neighbors to ensure its own water supply has undertaken conservation efforts that allowed it to help them meet theirs through the market.

Regulatory Adaptation

The market helps users adapt to changing conditions, but sometimes regulators have to adapt as well. One important provision of the Mojave adjudication, which is also typical of other adjudications, was the designation of de minimis, or minimal, groundwater users. Minimal users may pump small amounts of water for domestic uses and are assumed in aggregate not to affect the overall hydrologic system appreciably. One goal of designating minimal users is to make sure households in rural areas have access to drinking water; another is to avoid complexity in negotiations over the design of the management regime by exempting small users from it. In the Mojave, minimal producers are allowed to pump up to 10 acre-feet per year.

Recently, though, concerns have arisen in the Mojave that minimal users may be affecting the system—and potentially jeopardizing other users’ water reliability. The Mojave Water Agency began to note increases in total minimal producer pumping in 2015. These increases could affect others by pushing total aggregate use beyond sustainable levels. That could cause overdraft in the basin again or, depending on where new extraction occurs, restrict downstream flow and threaten the subarea delivery obligations described earlier.

The expansion of pumping by previously exempt parties can compromise the integrity of the adjudicated rights system. After 2015, the water agency worked with minimal producers to bring some of them into the adjudication system—quantifying their claims and subjecting them to the same rules as other significant producers. In addition, the agency has adopted a new ordinance to help control the impacts of minimal producers: New producers issued well permits for de minimis use will be subject to charges to help offset the impact of any new pumping on the system. The offsets occur through the purchase of imported water.

In short, changing economic conditions in the basin and associated increases in demands on water prompted adjustment to the management system. As the Mojave example demonstrates, effective management requires more than just caps; ongoing attention and action from regulators is necessary when system-wide benefits are at risk.

Learning from Mojave

Groundwater users elsewhere in California and throughout the American West have begun to study previous groundwater allocation and market systems for insights, including the Mojave’s approach. Several practical lessons for designing systems include incorporating hydrologic connections and using market approaches to resolve management issues.

The Mojave adjudication also highlights the importance of effective stakeholder engagement when it comes to implementing California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). While most major users accepted Mojave’s new management system in the early 1990s, several parties decided to challenge it in court, arguing it abridged their water rights. Even as trading commenced in 1994 with most groundwater pumpers on board, litigation and appeals kept in question the participation of some influential holdouts. The resulting California Supreme Court decision affirmed the holdouts’ rights. Coupled with court decisions from other groundwater adjudications, precedents may restrict the ability of groundwater managers to limit pumping under SGMA without broad stakeholder buy-in. In essence, bringing large pumpers into a binding agreement to constrain their entitlements could be difficult without their consent.

Absent such agreement, lengthy delays to resolve claims could arise. Given that efforts to implement SGMA in the past several years have been accompanied by a prolonged drought—and that droughts in the future will likely be more intense, heightening stresses on groundwater resources—there is an advantage to moving swiftly. Adopting systems that manage demand and allocate pumping rights sooner than later can avoid undesirable impacts of aquifer drawdown. Two pieces of California state legislation passed in 2015 attempted to streamline future adjudications and reduce the power of holdouts to stall the process; however, SGMA is explicit that it does not alter existing groundwater rights. The upshot is that implementing significant constraints on groundwater use without broad stakeholder buy-in may very well face strong pushback and delays.

Groundwater pumpers in the Mojave today have benefited greatly from their new management system. Stabilized water tables have reduced pumping costs and assuaged concerns about future water reliability. The market has facilitated flexible reallocation and increased the value of water in the basin. And the basin’s accounting framework provided a foundation for it to become a regional water bank, storing excess flows for out-of-basin water users during wet years to be extracted during droughts.

Groundwater users and managers throughout California and in other parts of the West may need to make similar transitions in the coming years, and they may need to do so quickly. But they cannot skimp on the details. A functioning system that meets users’ needs often requires more than just an aggregate cap and individual entitlements. A system designed for a desert can provide important lessons for them along the way.