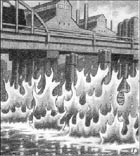

Early in the summer of 1969,

the Cuyahoga River caught

fire. Piles of logs, picnic

benches, and other debris had

collected below a railroad

trestle, which impeded their

movement down the river.

These piles only lacked a spark

to set them afire. A passing

train with a broken wheel bearing

probably provided that

spark, igniting the debris

which, in turn, lighted the

kerosene-laden oil floating on

top of the river.

The fire burned only 24

minutes-too short a time for

the Cleveland Plain Dealer to

catch a photo-and at first it attracted

little attention. However,

in the following months, the fire

became a symbol of a polluted

America. It helped galvanize the

environmental movement. Even

today, the idea of the burning

river remains a symbol of industrial neglect of the environment.

A few things have been ignored in the legend surrounding

the Cuyahoga fire:

- The Cuyahoga, which flows through the city of

Cleveland into Lake Erie, had caught fire at least

two times before (in 1936 and 1952). The earlier

fires burned much longer and caused much more

damage. - While oil on the river burned, most of the fuel was

not industrial but, rather, logs, debris, and household

waste washed downstream by the periodic storms that roil the deep, fastmoving

river many miles

above Cleveland. - Most important for our understanding

of environmental

problems, the fire came about

because political control replaced

the emerging commonlaw

rule of strict liability. Had

that doctrine been allowed to

hold sway, there would probably

not have been a fire in

1969.

The industrial stretches of

the Cuyahoga River were, indeed,

polluted in 1969 and had

been for many years. In the

1930s, for example, the people

of Cleveland had clean drinking

water from Lake Erie. So municipal

authorities left the

Cuyahoga River alone-allowing

firms along its banks to discharge

into it at will.

Not everyone was content with that policy. In

some cases Cuyahoga water was too polluted even for

industrial use. In 1936, a paper manufacturer on

Kingsbury Run, a tributary of the Cuyahoga, sued the

city of Cleveland to stop it from dumping raw sewage

into the stream.

The city responded by saying that it had used the

stream as a sewer since 1860 and that therefore it had a

“prescriptive right” to use it that way. The court agreed

with the city of Cleveland. It stated that when part of a

stream “being wholly within a municipal corporation, so

that none but its residents are thereby affected, is generally

devoted to the purposes of an open sewer for more than 21 years . . . it becomes charged with a servitude

authorizing its like use by other riparian owners.”(1)

So much for protection of riparian rights in 1936!

However, that attitude changed rapidly. By 1948, the

doctrine of strict liability was taking hold. A court decision

states that “one may not obtain by prescription,

or otherwise than by purchase, a right to cast sewage

upon the lands of another without his consent.”(2) Other

rulings were similar.

Incomes were rising and concern about industrial

wastes was mounting. Pollutants were corroding sewage

treatment systems and impeding their operation. In another

part of the state, the Ohio River Sanitation Commission,

representing the eight states that border the

Ohio River (which runs along Ohio’s southern border),

developed innovations to reduce pollution. The municipalities

and the industries along the Ohio began to invest

in pollution control technology.

Unfortunately, this progress soon

ended. The evolving common

law and regional compacts hit a snag

in 1951 when the state of Ohio created

the Ohio Water Pollution Control

Board. The authorizing law

sounded good to the citizens of Ohio.

It stated that it is “unlawful” to pollute

any Ohio waters. However, the law

continues: “. . . except in such cases

where the water pollution control

board has issued a valid and unexpired

permit.”(3)

The board issued or denied permits depending on

whether the discharger was located on an already-degraded

river classified as “industrial use” or on trout

streams classified as “recreational use.” Trout streams

were preserved; dischargers were allowed to pollute industrial

streams. The growing tendency of the courts to

insist on protecting private rights against harm from

pollution was replaced by a public decision-making

body that allowed pollution where it thought it was appropriate.

During the 1960s, attempts were made to revive

the application of common-law rights to stop pollution

of the Cuyahoga. Those complaints were redirected to

the state or local agency in charge of managing water

quality, with one exception. In 1965, Bar Realty Corporation,

a real estate company, sued the city and the

board to compel them to enforce the city’s pollution

control ordinances against industrial polluters. The

judge agreed, and directed the city and the board to stop pollution of the Cuyahoga.(4) However, the Ohio Supreme

Court overturned the ruling. The Supreme Court

decided that Cleveland’s ordinances were in conflict

with state statutes. Management by permit continued to

dominate other institutional arrangements on the

Cuyahoga.

Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes, who helped draw

attention to the Cuyahoga fire, criticized the state for

letting industries pollute. “We have no jurisdiction over

what is dumped in there. . . . The state gives [industry]

a license to pollute,” the Cleveland Plain Dealer quoted

him as saying (June 24, 1969). Stokes was not far off the

mark. However, he thought the solution was to move to

federal regulation rather than back to the guidance provided

by court decisions.

The famous fire illustrates the unfortunate history of

pollution control in the United States. Growing citizen

concern about pollution was leading to voluntary cleanup-as illustrated by the Ohio

River Sanitation Commission-but

the emerging common-law rule of

strict liability was abandoned in favor

of a political process that allowed continuing

pollution of certain segments

of the state’s waters.

By catering to special interests,

Ohio’s regulatory scheme stopped

the emergence of a doctrine that

would have spurred cleanup. It also

helped propel the nation toward national

legislation and its costly technological

specifications. The Clean

Water Act of 1972 may have led to change on the Cuyahoga, but it also stifled innovation

in pollution control and wasted vast sums of money,

both industry’s and the taxpayer’s.(5)

In sum, the Cuyahoga fire, which burns on in

people’s memory as a symbol of industrial indifference,

should also be viewed as a symbol of the weaknesses of

public regulation.

Notes

1. City of Cleveland v. Standard Bag & Paper Co.,

Ohio, 1905. 72 Ohio St. 324, 74 N.E. 206.

2. See Vian v. Sheffield (June 14, 1948), 85 Ohio

App. 191, 88 N.E. 2d 410, at 199. The decision cites

four other precedents. See also Weade v. City of Washington

(July 15, 1955), 128 N.E. 2d 256. While Vian involved

the overflow of contaminated water onto a

person’s land, those living along rivers had riparian

rights to nondeteriorated water quality.

3. The Water Pollution Control Act of Ohio, Sec. 1261-1e of the Act, Violations of Act Defined.

4. Bar Realty Corp. v. Locher, Ohio, 1972. 30 Ohio

St. 2d 190, 283 N.E. 2d 16.

5. See pgs. 76Ã77 in Bruce Yandle, Common Sense

and Common Law for the Environment, Lanham MD:

Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (1997).

Stacie Thomas, a 1998 PERC Fellow, is an economist with the Senate

Banking Committee in Washington, D.C. More information about the

Cuyahoga fire and common law can be found in “Burning Rivers,

Common Law, and Institutional Choice for Water Quality,” forthcoming

in The Common Law and the Environment, ed. Roger E. Meiners

and Andrew P. Morriss, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (1999).