Protecting private property rights is critical to protecting environmental resources because private landowners respond to incentives. When landowners can profit from stewarding game animals, fish, wetlands, forests, or streams, one can expect these resources to flourish. Conversely, environmental resources that generate costs to landowners or compromise their privacy will likely suffer from neglect at the landowner’s hand.

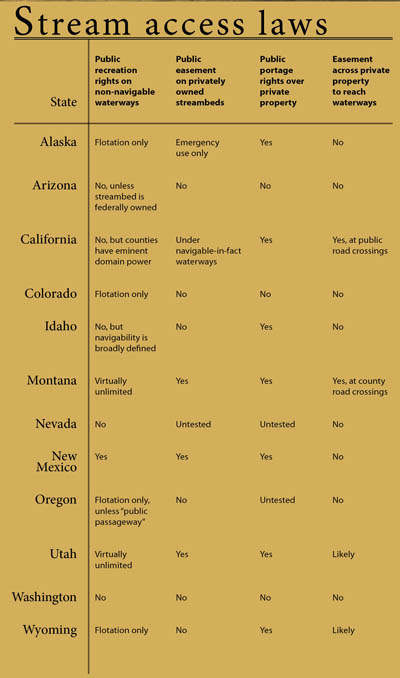

The critical distinction is whether the landowner views the resource as an asset or as a liability, and that depends largely on the landowner’s property rights. Nowhere is the relationship between property rights and stewardship better demonstrated than in the context of stream access laws. These laws define the public’s right to access non-navigable streams and, in so doing, they impact the rights and stewardship incentives of riparian landowners.

Access laws that expand public use rights beyond navigable waterways and onto privately owned streambeds undermine the property rights and privacy expectations of riparian landowners, forcing the label of liability onto streams flowing through private land. As a consequence, such laws remove the incentive for riparian landowners to invest in stream restoration or fish habitat— investments that generate public benefits.

Western States with Unlimited Stream Access

Landowners are less likely to protect and improve fish habitat or a stream’s natural hydrology, which is tied to a variety of important ecological functions such as storage of flood waters, recharge of groundwater, treatment of pollutants, and habitat diversity, if they have no meaningful way of limiting public access to their investment. Litter, erosion, property damage, invasions of privacy, over-fishing, and in some cases legal liability all increase when there is unlimited public access to streams flowing over private property. These costs lead landowners to view non-navigable streams as liabilities rather than assets. The following states have the most liberal stream access laws.

Montana

Montana has led the way in the erosions of private property rights since the Curran opinion in 1984, which used the public trust doctrine to define the limits of public stream access. In that opinion, the Montana Supreme Court held that “under the public trust doctrine and the Montana Constitution, any surface waters capable of use for recreational purposes are available for such purposes by the public, irrespective of streambed ownership.”

Two recent court cases in Montana have further expanded the public’s recreation rights on private stream beds and discouraged private stewardship of non-navigable waters. In PLAA v. Comm’rs of Madison County (2008), district judge Loren Tucker ruled the public could use county road bridges to access non-navigable streams flowing through private property. And in Bitterroot Protective Association Inc. v. Montana Dept. of Fish, Wildlife and Parks (2008), the Montana Supreme Court ruled that a reclaimed irrigation ditch supplied exclusively by a headgate and irrigation return flows qualified as a natural, perennial flowing stream open to public recreational use. Landowners along the Mitchell Slough had invested thousands of dollars and countless hours building a vibrant trout fishery out of an agricultural ditch. No matter. With the stroke of a pen (actually, it took 54 pages to explain its reasoning), the court signaled that in Montana good stewardship would not go unpunished.

Utah

Echoing Montana’s boundless interpretation of the public trust doctrine, the Utah Supreme Court recently ruled in Conaster v. Johnson (2008) that the public’s easement over all natural waters in the state implies an easement over privately owned stream beds and banks. While anglers in Utah applauded the opinion, several landowners in the state halted stream restoration plans as soon as they learned of their inability to ward off the fishing masses. Just like the Mitchell Slough in Montana, vibrant fisheries in Utah may be sacrificed in the name of public access.

Oregon

Oregon follows a more complex process for determining the public’s recreational rights across privately owned stream beds —the “public use navigable” test. According to a 2005 opinion by the Oregon Attorney General, “the Oregon Supreme Court has established a state public use doctrine that gives the public the right to make certain uses of a waterway whose bed is privately owned if the waterway has the capacity, in terms of length, width, and depth, to enable boats to make successful progress through its waters.” Though not as far reaching or automatic as the stream access laws in Montana and Utah, few waterways in Oregon are free from public access.

States Protecting Private Property Rights

The following states continue to protect the private property rights of riparian landowners and, in so doing, protect their incentive to create viable fisheries and restore natural stream hydrology.

Colorado

Colorado has protected the private property rights of riparian landowners more so than any other state in the West. Although the Colorado Constitution declares the unappropriated water of every natural stream public property, members of the public are not allowed to touch privately owned streambeds without the owner’s permission to do so, regardless of navigability.

Examples of large-scale, privately funded stream restorations in Colorado are too numerous to list, but take for example David Pratt’s restoration efforts along the Little Snake River. The project was the largest privately funded river restoration project in the history of the Army Corps of Engineers district and, according to the Three Fork Ranches’ website, the only project in recent memory supported by the Sierra Club. After Pratt successfully restored natural stream bank stability and created wetlands and off-channel fisheries, several downstream neighbors restored an additional 16 miles of the Little Snake. If every angler in Colorado held access to this stream, these landowners would have viewed it as a liability rather than an asset and left the river in its channelized, fishless condition.

Arizona

Applying the federal test for commercial navigability, the Arizona Navigable Stream Adjudication Commission has determined the Colorado River to be the only navigable waterway in the state. Consequently, the public has recreation rights to the Colorado River. Title to stream beds under non-navigable waterways remains either with the federal government or private individuals, depending upon ownership at Arizona’s statehood. Although the public may recreate on waters above federally owned streambeds, it has no such right to access waters above privately owned streambeds.

California

California was the first state to apply the public trust doctrine to environmental resources, but unlike Montana, California has not extended the doctrine to include public access to non-navigable waterways. Interestingly, however, each county’s board of supervisors has the authority to contract for public access rights along certain non-navigable waterways. If negotiations fail the county boards may exercise the state’s eminent domain powers to take the private property, but this statutory authority at least recognizes the private property rights of riparian landowners. In California there is no right to trespass across private property to access navigable waters, and county roads serve as public access points only to navigable waterways.

Battleground States

Nevada

Although the Nevada Supreme Court has retained the federal navigability test—one that is deferential to private landowners—neither the court or the legislature has addressed the issues of whether the public trust doctrine extends to non-navigable streams or whether recreationists may float or wade over privately owned streambeds.

Alaska

Interpreting the state’s stream access law, the Alaska Supreme Court stated in Wernberg v. State of Alaska (1974) that “it was the intent of the state legislature to permit the broadest possible access to and use of state waters by the general public.” The public therefore appears to have flotation rights on non-navigable rivers and streams. Nonetheless, the Alaska Attorney General opined that the public does not possess the right to use privately owned streambeds under non-navigable waterways except in emergency situations.

Wyoming

Although the Wyoming Supreme Court stated in Day v. Armstrong (1961) that “actual usability” defines the public’s ownership of and right to use water in non-navigable streams, this does not appear to include the right to walk or wade along privately owned stream bottoms. According to the Armstrong opinion, however, recreationists might have rights of ingress/ egress over private property as necessary to reach usable waterways.

Incentives for Streams

Whether riparian landowners can legally limit public access to non-navigable streams is a key determinant in whether those landowners view those streams as assets or liabilities. In states that limit public access to non-navigable streams, landowners have an incentive to improve fish habitat and the stream’s natural hydrology. Those states that allow near limitless public access do so at the expense of private stewardship efforts that often create valuable public benefits. States that have yet to directly address the issue of non-navigable stream access would be wise to consider the incentives to private riparian landowners and the positive impact they can make on the state’s stream resources.

Note: The information contained in this article is for summary purposes. Ask before you recreate.