For nearly a century, a popular story has linked the origins of the National Park Service to the genius of one man. In 1914, Stephen T. Mather, a self-made millionaire in the borax industry, visited Yosemite and Sequoia national parks. Finding both of them poorly managed he wrote Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane and complained. “Dear Steve,” Lane allegedly replied, “If you don’t like the way the national parks are being run, come on down to Washington and run them yourself.” Mather accepted and within two years, as the story goes, he convinced Congress to pass the bill creating the National Park Service. He was then appointed as the agency’s first director and promised to manage the parks “on a business basis.” If making a fortune had taught Mather anything, it was that every park should be run like a business, given that the government always seemed strapped for funds.

The durability of the story may be credited to Horace M. Albright, the Park Service’s second director and lifetime publicist. On becoming Mather’s assistant in 1915, he was already a shrewd judge of the press. A story well told—and repeatedly told—grew ever harder to refute. Until his death in 1987, Albright was never at a loss to explain how the Park Service came to be. The reason was Stephen Mather. Certainly, whenever Albright was invited to explain his own role, he instantly demurred. No legend should have two heroes. Thus Albright, in the words of his biographer Robert Cahn, refused “to take anything away from the place Mather holds in history as the ‘founder’ of the National Park Service.”

However laudable, Albright’s limited history comes with pitfalls, even to slight how the national parks in fact evolved. Before Mather had reached the age of five, the Philadelphia financier Jay Cooke had prevailed on Congress to establish Yellowstone as a “public park.” Chartered in 1864, his proposed Northern Pacific Railroad was to cross Montana some sixty miles to the north. Like the nation’s first park, the Yosemite Grant of June 30, 1864, Yellowstone obviously presented a business opportunity. As the Yosemite Grant already specified, “leases not exceeding ten years may be granted for portions of said premises.” If Yellowstone became a government park, Congress would likely repeat that language, allowing Cooke’s railroad—as Yellowstone’s only railroad—to win such leases for itself.

The point is that the “business basis” for establishing parks well predates Mather—and its chief practitioner was the railroads. In the fall of 1871, Cooke further pursued the Yellowstone matter with Ferdinand V. Hayden, director of the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. Hayden had just returned from Yellowstone and would be preparing his report to Congress. Might the report include the following recommendation, Cooke asked? “Let Congress pass a bill reserving the Great Geyser Basin forever, just as it has reserved that far inferior wonder the Yosemite valley and big trees.” Of course, there was nothing inferior about Yosemite. It was just that Cooke’s railroad would not be going there.

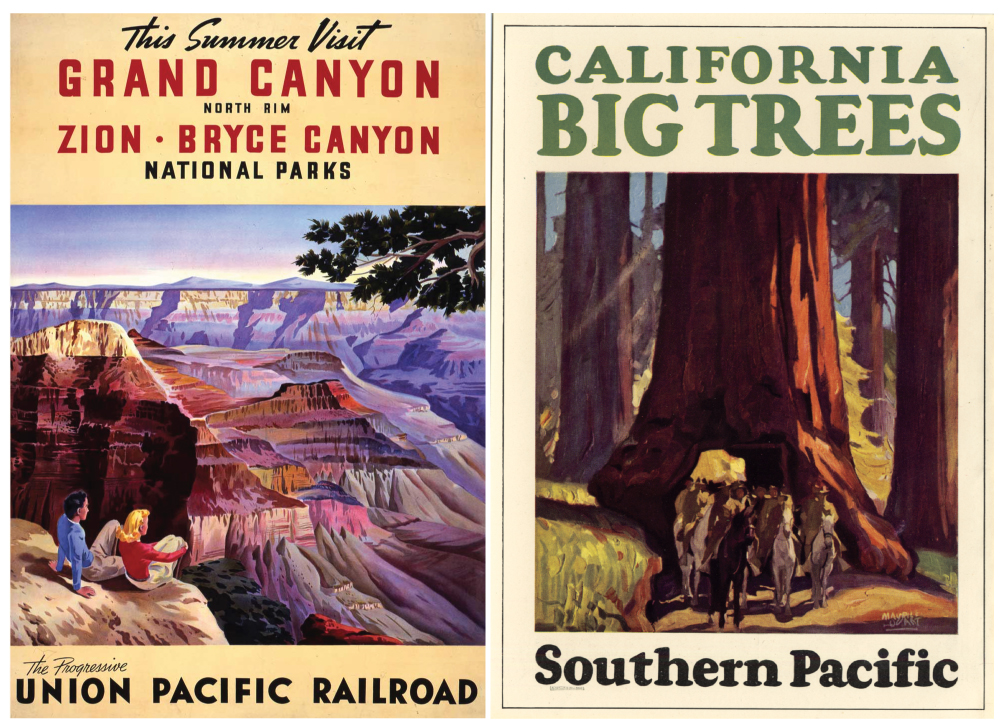

Naturally, Cooke wanted a park of his own, as would every railroad in the West. Preservationists then saw their opportunity. “Even the soulless Southern Pacific Railroad,” John Muir informed the Sierra Club in 1895, “never counted on for anything good,” had helped “nobly” to expand Yosemite in 1890. Muir might have also mentioned Sequoia and General Grant national parks, which had actually passed Congress the week before. There again, the railroad’s chief lobbyist in Washington, D.C., had been instrumental in making the case for protecting all three California parks.

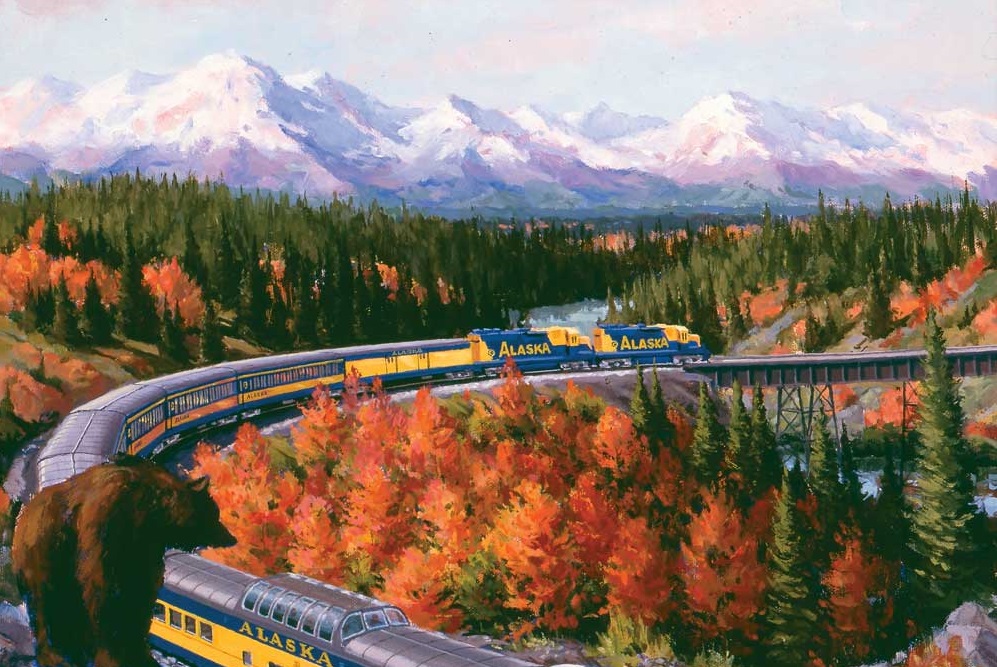

Between 1890 and 1915, there followed a wave of railroad support leading to the expansion of the national park system, including its most enduring parks. In 1901, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway arrived at the South Rim of Grand Canyon. Although park status for the canyon was years away, the railroad was confident it would happen. Following the establishment of Glacier National Park in 1910, its development proceeded grandly under the auspices of the Great Northern Railway. By then, Crater Lake, Mount Rainier, and Mesa Verde national parks were also important railroad destinations. Rocky Mountain National Park, established in 1915, similarly won support from the Union Pacific, Rock Island, and Chicago, Burlington and Quincy railroads.

The truth is that Mather had “discovered” nothing. On his arrival in Washington, D.C., he already had the railroads at his back. What he called putting the parks “on a business basis” had been their mantra all along.

It was under the railroads that Americans had formed a clear understanding of what the parks should be. Most important, the railroads were the ones supporting better management, as well as the establishment of additional parks. As for protecting the parks in perpetuity, the railroads had always agreed. Mather was just the latest visionary in a long evolution of visionaries dating back to 1864.

In fact, ever since their founding the railroads had discovered the business advantages of respecting landscape. Mines, mills, and factories were necessary evils; otherwise, unspoiled scenery attracted travelers. Where respect was absent—most notably at Niagara Falls—the scenery was a mess. Piling in, private entrepreneurs had destroyed the cataract’s environs without any thought to the future. The railroads realized they could sell the American landscape if profit and restraint went hand in hand.

Embracing the general landscape and the national parks, the railroads perfected a disciplined engineering style. Especially on approaching the parks, tourists would expectantly scan the countryside for signs of the grandeur yet to come. Even at great distances from the parks, it was important that natural formations not be defaced. In the East, railroads had already taken the lead in objecting to billboards, and finally just ordered their track gangs to tear them down. In the business of selling tickets, the railroads needed to respect what a majority of their passengers wished to buy. A railroad lined with billboards would likely be bypassed for another, more scenic route.

Although bankruptcy eventually cost Jay Cooke his opportunity, he left no greater mark on the Northern Pacific. With Yellowstone as the prize, his successors continued to plan the railroad with special care to the natural scenery. Frederick Billings, perhaps the railroad’s most famous president, instructed his track crews to read the landscape, with a special emphasis on the Yellowstone River Valley as Yellowstone Park’s grand approach.

AS FOR THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, it properly traces its origins to the U.S. Army as the first protector of the parks. Cavalry troops began patrolling Yellowstone as early as 1886. There followed a call to make protection uniform. In 1900, Representative John F. Lacey of Iowa asked Congress to pass his bill for the management of national parks. J. Horace McFarland then revived the proposal in 1910 as president of the American Civic Association.

McFarland’s role proved to be critical. A successful printer and publisher from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, he envisioned a “bureau of national parks” and over the next six years threw the weight of the American Civic Association behind the idea. The initial government endorsement came from Richard A. Ballinger as secretary of the interior. By 1911, President William Howard Taft was also on board.

Five years before Mather was saying it, McFarland hoped to put the parks “on a business basis.” Congress especially, McFarland realized, would look to the railroads for their opinion. Succeeding Richard A. Ballinger as interior secretary, Walter L. Fisher also agreed, and immediately called for a two-day conference in Yellow-stone to meet with railroad executives. Conferees gathered after the height of the 1911 tourist season in the rustic Old Faithful Inn. “We thoroughly appreciate the expenditures which the railroads have made in many instances for the development of the parks,” Fisher began. “I mean expenditures made in the furnishing of increased facilities in getting to the parks, and particularly the work of publicity which they are carrying on. We know that costs them money, and although the inducement is a financial return to the railroads, it is an enlightened selfishness which is entitled to our grateful recognition.”

Louis W. Hill, as president of the Great Northern Railway, agreed. “Our relations with the national parks are naturally very close, and I believe they should be closer,” he said. Hill’s personal interest was in Glacier National Park, approved by Congress the year before. However, he further intended to defeat Canada and Europe in the “war” for American tourists. “See America First” was his war cry. “The railroads are greatly interested in the passenger traffic to the parks,” Hill repeated. “Every passenger that goes to the national parks, wherever he may be, represents practically a net earning. We already have the facilities for taking care of the regular traffic and the tourist earnings are practically net, as long as they do not require extra train service.”

Including Hill, seven railroad executives led off the Yellowstone conference, each offering a variation on his speech. On cue, J. Horace McFarland then introduced the proposal for a bureau of national parks. “The parks are successful when they are the primary object of attention on the part of some one person or some definite body,” he said. “The parks, broadly considered, properly supported, adequately laid out, and suitably maintained, will be more advantageous, even as a solid business proposition, than anything we can do today.”

In 1912, and again in 1915, two additional parks conferences confirmed the popularity of the “See America First” campaign. There followed another booming endorsement on the fairgrounds of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. Designated by Congress as the official celebration for the completion of the Panama Canal, the world’s fair electrified nearly 19 million visitors and attracted the railroads as major exhibitors. Over four acres known as “The Zone,” the Union Pacific Railroad created a model of Yellowstone, including a full-size replica of Old Faithful Inn. The Santa Fe Railway contributed a six-acre model of Grand Canyon, offering visitors “parlor car” rides along the rim.

Here especially, Stephen Mather was a latecomer to the party. The railroads had been planning their exhibits for at least three years. Once the National Park Service became part of their planning, there was no holding the railroads back. They wanted the agency and said so openly—joining the ranks of preservationists on Capitol Hill. By that time, Congress had all the proof it would ever need. Americans loved their national parks—and wanted them properly managed. As of August 25, 1916, the National Park Service was approved.

FAST FORWARD, THEN, TO THE PRESENT. As the National Park Service prepares to celebrate its centennial in 2016, can the agency afford to ignore this larger history? The railroads, rather than Stephen Mather, truly founded the national parks and put them on the path to be managed on a business basis. With the challenges the Park Service faces as it enters its second century, why does the agency fail to recognize this storyline today?

Instead of celebrating its past, the agency seems inclined to stir up doubt. Certainly, the new word at Park Service headquarters is relevance. Are the parks doing enough to attract minorities? Will the millennial generation ever support conservation? It is as if the agency never stopped to think what it is really saying: Somehow, the national parks are flawed.

In the treatment of business, too, we see the phenomenon that loving the parks while hoping to profit from them is increasingly suspect. Every motive to profit must be explained. The attempt at explanation can prove insufferable, such as concessionaires describing themselves as “green.” In the past, the railroads did not have to constantly prove themselves, and so could engage in real protection. A commitment to preservation certainly demanded greater proof than substituting paper for plastic.

Railroad history is to remind us why the parks are not flawed, whether in terms of business opportunities or social relevance. In 1915, swelled by travel to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, Yellowstone’s visitation still barely exceeded 50,000. The vast majority of the population could not afford the trip. Why did the railroads—shortly to be five companies serving Yellowstone—persist in making the effort? Because the railroads also understood the profit in being patient. If anything is missing today, it is that earlier willingness to secure the parks, and then worry about attracting visitors, a patience for which the railroads were justly renowned.

If indeed we want the national parks to succeed, we should rethink that term from their railroad past: “enlightened selfishness.” Why are there no light-rail systems in the national parks, for example? Twenty years ago, one proposed for the South Rim at Grand Canyon was rejected. Several proposed for Yosemite Valley have never gotten to the planning stage. The automobile is solidly within the parks. Why not “patient” transport—why not the railroads—that secured them in the first place?

If “enlightened selfishness” taught us anything, it was to be honest in planning the parks. No longer do they lack for visitors; they rather lack for an enlightened approach to access. Consider the real problem railroads might address—how to accommodate 275 million visitors each and every year.

New generations of Americans will find the parks. New generations always have. Meanwhile, this is no time to forget how preservation actually works. In the century ahead, whatever consensus looks like, it should still represent “enlightened selfishness.” No term more eloquently reaffirms why business is as vital as ever to the future of the national parks, starting again with transportation options that make sense.