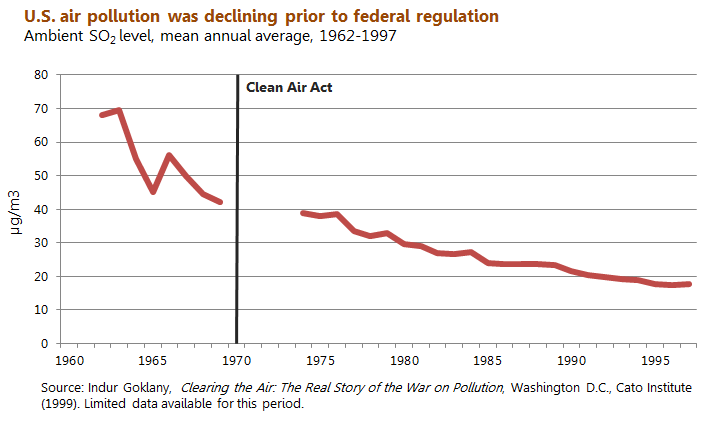

Here’s a surprising fact: At least 70 percent of the reduction in U.S. air emissions since their 1930s peak occurred before the Clean Air Act was passed in 1970.

We typically hear that the Clean Air Act was responsible for most, if not all, of the improvements in U.S. air quality over the last century. The truth, however, is that local governments passed ordinances to reduce harmful emissions decades before the federal government acted. Moreover, consumers had already begun demanding “cleaner” goods and services, like natural gas to replace coal for heating and cooking.

Indeed, after Congress passed the Clean Air Act in 1970, the rate of improvement in air quality actually slowed. Why? The low-hanging fruit had been picked. Plus, federally mandated reductions often failed to account for local conditions, creating expensive and often ineffective one-size-fits-none approaches to clearing the air.

This history raises two questions. First, if it wasn’t intervention by the Environmental Protection Agency, what motivated those early air quality improvements? And, second, why has the federal government received more than its fair share of the credit?

Three words can answer the first question: Wealthier is healthier. And just one might suffice to answer the second: visibility.

Wealthier is Healthier

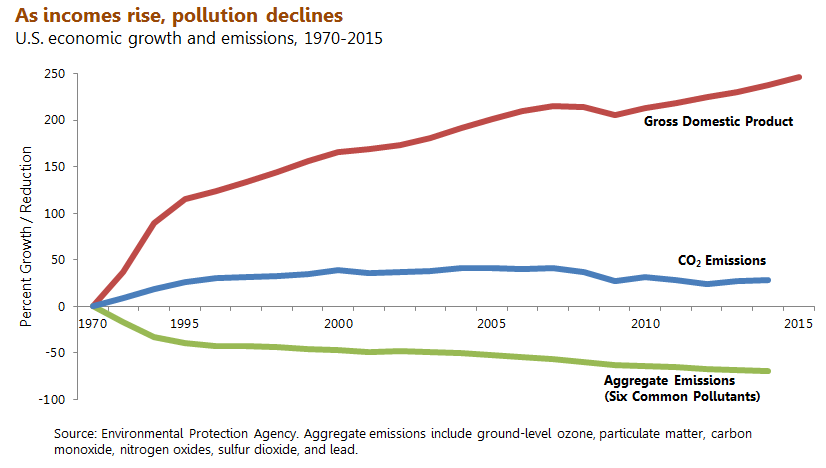

As people get wealthier—that is, once they meet their basic human needs of food, water, and shelter—they begin to demand a cleaner and cleaner environment. We observe this phenomenon within countries (by tracking environmental indicators as economic prosperity changes over time) and across borders (by comparing poor and wealthy countries). Although there is often an initial increase in environmental degradation as incomes and levels of consumption rise, at a certain point that degradation slows and eventually reverses as people become wealthier.

One of the first things to improve is water quality because contaminated water often makes people sick immediately. Soon after, air quality improves, first for the visible irritants that have immediate health impacts (particulates and smog) and later for the less conspicuous emissions that cause problems downwind (acid rain precursors).

Outcry or Outcomes?

If a combination of market forces and local government action had already achieved most of our air quality improvements before passage of the Clean Air Act, then why does this law receive such full and undue credit?

The answer, I believe, is visibility. The Clean Air Act is an enormously expensive law that increases the price of many of the goods and services you consume today. The act regulates everything from the tail pipe of your car to the smokestack of the nearby power plant, costing the United States approximately $60 billion in compliance each year. And the law, itself, was passed amid a flurry of environmental legislation in the 1960s and 1970s, when public outcry over the nation’s air, water, and species loss was at a fever pitch.

Meanwhile, the hero of earlier air quality improvements—economic prosperity, guided by an “invisible hand”—was mistaken for the villain. Taking the long view, we now know that economic wealth and environmental health go hand in hand. While public outcry might drive environmental legislation, it is ultimately economic growth that drives positive environmental outcomes.

Applications to Climate Change

As our growing wealth allows us to address increasingly remote threats to our health, it is easy to understand why there has not been meaningful action to reduce global concentrations of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide: The projected harms from climate change are far off in the future and uncertain, while the costs to reduce those concentrations are significant and would be incurred today. Moreover, greenhouse gas emissions, much of which come from developing countries, affect the entire atmosphere and don’t necessarily produce direct, local impacts like other emissions.

The question is whether greenhouse gases will create sufficiently acute health threats that action to address them is warranted. Or, alternatively, might global prosperity reach such high levels that adapting to the effects of climate change is relatively cheap?

Whichever scenario plays out, we should be wary of any proposed policies that would make the world poorer and therefore limit our ability to adapt. Rather, we should celebrate economic wealth for the environmental health it bestows and do all we can to encourage its future growth.