She is a stocky little bay with a sock, a star, and a snip. To some, she embodies the spirit of the American West; to others, she symbolizes the tens of thousands of wild horses that threaten the viability of its arid rangelands.

She came from the Jackson Mountains in northern Nevada, born on the range somewhere between the gold fields near Winnemucca and the annual Burning Man gathering in the Black Rock Desert. On an October day in 1997, the two-year-old filly was herded into government corrals by wranglers on horseback with assistance from a helicopter, never to return to the slopes of King Lear or Parrot Peaks. But she was fortunate because she avoided the miserable fate of some wild horses—chewing off each other’s tails in their desperate search for nutrition on the barren range or dying hung up in barbed-wire fences in frantic quests to find water. In February 1999, after nearly 16 months in the care of the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the mare—then four years old—was relocated from public rangelands into private hands, adopted by a new owner in Ohio for a $125 fee.

Thousands of horses and burros just like her—whose ancestors were too wild, too remotely located, or were released by farmers decades ago when tractors replaced them—now roam wild in the western United States and are protected by the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971. A nation with more real cowboys would mold this natural resource into a remuda unmatched in the world, suitable for Border Patrol agents, National Park police, or even the Interior Secretary to ride to work. But as Neil Young, Willie Nelson, and others have reminded us, real cowboys are hard to find. Wild horses, on the other hand, are not—government holding pens teem with tens of thousands of them.

The policies employed by the Bureau of Land Management to manage the estimated 67,000 wild horses and burros on public rangelands in the western United States are controversial for a variety of reasons. Wild horse advocacy groups have argued continuously and strenuously for the well-being of horses. Other groups that have a stake in western public land management have also contributed to the debate. These include ranchers who lease public rangelands for livestock grazing, advocates for other wildlife that compete with horses for forage and water, and environmental groups concerned with rangeland health threatened by excess populations of wild horses and burros.

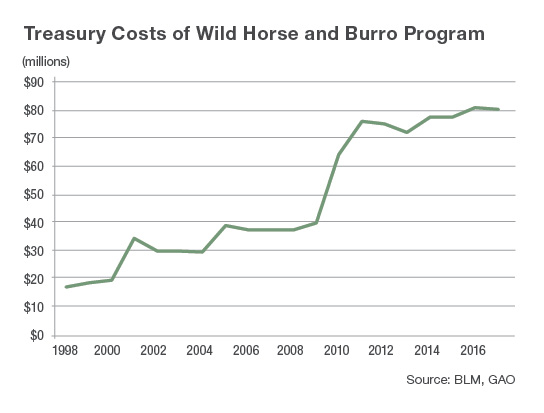

In addition to disputes over land use and animal welfare, another concern has been the rising costs of current policies. Between 1998 and 2016, appropriations for the wild horse and burro program more than quintupled, from $15 million to $80 million. Last year, former BLM Director Neil Kornze estimated that taxpayer costs to care for the 46,000 wild horses currently held by the BLM in long-term, off-range corrals and pastures would exceed $1 billion over the course of the animals’ lifetimes. Horses in these holding facilities typically have been captured by the agency, vaccinated, held in short-term facilities for up to two years, and offered for adoption at three separate auctions without a single buyer offering the minimum bid of $125. Kornze recently cited estimates that these lifetime costs would reach $50,000 per captured horse.

Why are taxpayers shelling out $50,000 a head to care for horses whose value is so low that no qualified private horse buyer is willing to offer $125 for one? In our recent research, we conduct an economic analysis of the federal government’s wild horse and burro program and consider several policy alternatives to address these and other questions. But to begin answering them requires disentangling the biological, political, and economic problems inherent in managing wild horses and burros.

A History of the Program

Early attempts to manage wild horses involved private landowners capturing and training the best animals in the herds and culling the others. In 1959, legislation prohibited the use of motorized vehicles to capture and kill wild horses and burros on public lands, but it did not establish a clear legal status for the animals, nor did it provide for enforcement of the law’s provisions.

In response to lobbying efforts by wild horse advocates, Congress unanimously enacted the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act in 1971. The act mandated that the secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture Departments protect and manage wild horses and burros on government-owned rangelands to achieve and maintain a “thriving natural ecological balance.” In response, the agencies established management areas where wild populations could be maintained over the long run.

If left unmanaged, wild horses and burros—which are not native to the United States and have no natural predators—double in number every four to five years. This biological reality soon presented problems under the Wild Horses and Burros Act. As populations rapidly increased, rangeland quality deteriorated so badly that some of the protected animals died of starvation. In response, the BLM removed wild horses and burros from the range and put them up for private adoption, with the first of these taking place in 1973. In 1976, following favorable public response to the initial auctions, the agency implemented a nationwide adoption program, which continues to be the primary mechanism for transferring horses and burros from the BLM to private owners.

In 1978, the Public Rangelands Improvement Act directed the secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture Departments to determine appropriate horse and burro population levels for each management area, as calculated based on the capacity of federal rangelands to sustain the animals. When population estimates suggest that the number of horses in an area exceeds the maximum acceptable level, the BLM conducts “gathers” to reduce on-range populations to acceptable levels. During these gathers, private contractors wrangle horses and burros into temporary on-site corrals, where the BLM selects animals to permanently remove from the range. The remaining animals are released back into the wild.

Animals that are selected for removal during gathers are taken to short-term holding facilities where they are vaccinated and freeze-branded with unique government identification codes. They are then eligible to be adopted by private buyers through the government’s Adopt-a-Horse program. Qualified buyers can acquire a horse at a competitive auction with a minimum bid of $125. Buyers obtain title to horses only after a 12-month probationary period and after they agree not to sell the adopted animals for slaughter, among other restrictions.

The Adopt-a-Horse program, however, fails to secure bids for all the horses rounded up from the open range. To address the growing inventory of unadopted horses, in 2004, Congress implemented an additional way to transfer horses to private parties by allowing the BLM to sell wild horses and burros that are more than 10 years old or that have been unsuccessfully offered for adoption at least three times. No limits are placed on the number of horses that can be sold through this mechanism, and prices are negotiated by the BLM on a case-by-case basis. Title is transferred at the time of sale, and no limitations are imposed on purchasers except that resale for slaughter is prohibited. In our analysis, we find that between 2005 and 2010, about 4,100 horses were sold using this option at an average price of $17 per horse.

Horses that are neither adopted nor sold are transferred to long-term holding facilities where the animals live out their days, often for up to 25 years or more. Most long-term holding facilities are located on private pastures in midwestern and western states and leased by the government for multi-year periods.

Wrangling the Costs

Today, there are approximately 67,000 wild horses and burros on the range—more than double the current target population of about 27,000. In other words, to comply with the provisions of the Wild Horses and Burros Act, the BLM would have to remove 40,000 horses from the range.

The rapid increase in the number of animals on the range in recent years illustrates the BLM’s predicament. Over the past three years, the growth rates of horses and burros on public rangelands have averaged 18 percent. At that rate, the population will double every four years—meaning it could more than quintuple to 350,000 animals in a decade—unless the agency increases its removals.

Why are taxpayers shelling out $50,000 a head to care for horses whose value is so low that no qualified private horse buyer is willing to over $125 for one?

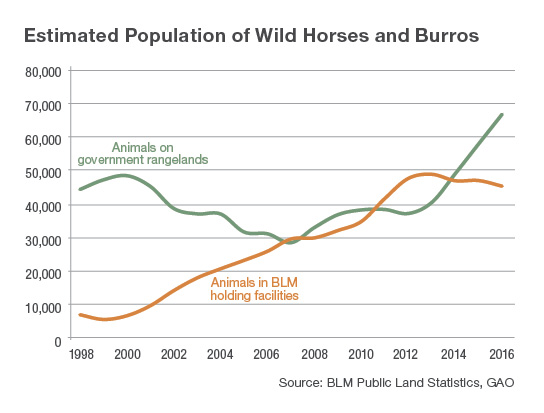

Horse and burro populations in both short- and long-term BLM holding facilities have also been increasing. The number of animals held by the agency grew from an average of about 7,000 from 1998 to 2000 to more than 45,000 in every year since 2012. Since the late 1990s, the share of the wild horse and burro program’s budget devoted to holding costs roughly doubled, from about one-third to two-thirds.

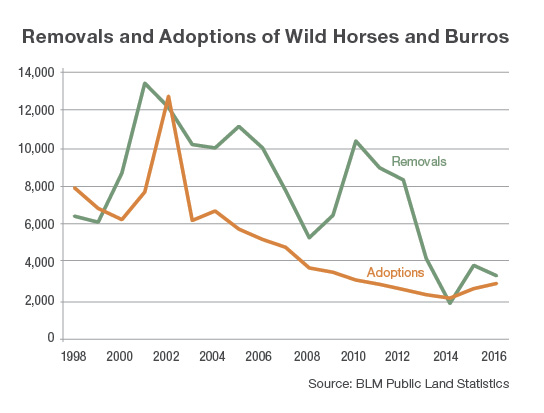

Gathering more wild horses from public rangelands doesn’t solve the problem—it only pushes it off the range. Between 2001 and 2006, 10,000 to 14,000 animals were removed each year, and in all but one of those years, removals exceeded adoptions, meaning that more animals are being held in government-run holding facilities. Furthermore, gathers are a point of contention for wild horse advocacy groups who object to the need for, and the techniques used in, reducing range populations. Since 2013, the BLM has removed fewer animals from federal rangelands, and the difference between removals and adoptions has been relatively small. This has slowed the growth in the inventory of horses held by the BLM, but it has contributed to the growth in on-range populations.

As a result of these management choices, the costs to taxpayers of the wild horse and burro program have risen markedly in recent years. The BLM now spends about $80 million each year on the program, with a large portion of that spent caring for thousands of horses that private buyers are not willing to pay $125 to adopt. Although the reduction in animal removals over the last few years has resulted in both the number of wild horses held by the BLM and the taxpayer costs of the program leveling off, the agency faces a dilemma. If all 40,000 excess animals currently on the range were gathered in the near future, then the costs of holding them could add roughly another $1 billion to the costs of the program over the lifetimes of the captured animals. On the other hand, if the animals are left on the public lands where they now roam, they’re likely to degrade rangelands, leaving the public-range resources one drought away from a calamity that no group—not the BLM, stockgrowers, horse advocates, or environmentalists—wants to see.

Reining in the Problem

Clearly, the BLM must change the way it manages wild horses and burros. From an economic perspective, the problem is that there are more wild horses and burros offered for adoption by the BLM than prospective buyers are willing to purchase at the $125 minimum. There are three options that could help address the problem: decrease the supply of wild horses, increase the demand for them, or decrease the minimum acceptable price for adoption. The BLM has taken steps along each of these margins, but frequent opposition from one interest group or another has stalled its efforts.

The excessive supply of wild horses ultimately stems from the fecundity of their on-range populations. The BLM has experimented with equine contraceptives such as the vaccine porcine zona pellucida, which reduces conception rates but is expensive to administer and is only effective for a relatively short period. Other attempts have been foiled by controversy. Last fall, for instance, in response to a lawsuit filed by a wild horse advocacy group, the BLM withdrew from a cooperative research effort with Oregon State University to develop new and more effective contraceptives. Another approach would be to increase the amount of public land available to wild horses, thereby decreasing the number of horses that need to be offered for adoption in the short term. But with the wild horse population growing 18 percent annually, any forage on additional acreage would be quickly consumed. And because there are currently no “unused” acres, devoting more rangeland for wild horses would mean displacing domestic livestock or other wildlife species. This situation reflects a political problem rather than a scientific one.

From an economic perspective, there are three options that could help address the problem: decrease the supply of wild horses, increase the demand for them, or decrease the minimum acceptable price for adoption.

To bolster demand, the BLM has partnered with several horse-training programs, including high-profile efforts like “Extreme Mustang Makeover,” sponsored with the Mustang Heritage Foundation, to feature professional trainers working with charismatic wild American mustangs. One benefit of such programs is that wild horses are trained and subsequently made available for adoption. Our research suggests that the demand for these trained horses is high enough to fetch prices that more than cover training costs. In addition, the BLM engages in training programs with several western state penitentiaries, in which prisoners work with horses to make them more readily adoptable. Given the looming financial burden of unadopted animals stemming from the reality that the number of on-range animals will have to be reduced in the near future, the agency would do well to pay for training if it continues to decrease the number of excess animals destined for long-term holding.

Since 2004, the BLM has had the option to sell certain wild horses outside of the Adopt-a-Horse program. This is certainly a step toward lowering the minimum offer price, but this option is currently only available for horses that are at least 10 years old or have failed to attract the minimum adoption bids multiple times. Several thousand animals have been sold under this option, and the BLM’s proposed 2018 budget calls for an expansion of these sales. This option, however, brings its own concerns—primarily that some high-volume buyers may purchase animals only to illegally send them to slaughter in Mexico or Canada.

Another seemingly feasible option would be to lower the minimum acceptable bid at Adopt-a-Horse auctions—perhaps even to a negative price. For instance, suppose the BLM actually paid people $100 to adopt wild horses. If so, the agency could save taxpayers almost $50,000 for each horse that would otherwise live out its days in BLM holding facilities. Our analysis suggests that with such a $100 payment by the BLM, almost all the animals placed in long-term holding over the last several decades would have been adopted, and taxpayers would have saved $450 million. Implementing this strategy, however, might require amending the Wild Horses and Burros Act.

The BLM and wild horses are caught between two rocks and a hard place. One rock is existing users of government land such as livestock producers and other forms of wildlife that compete for finite rangeland resources. The second rock is wild horse advocacy groups that view any reduction in on-range populations as inhumane to the animals. The hard place is the reality of increasing program costs and the need for ever-greater appropriations. Over the past two decades, the dramatic increases in taxpayer costs suggest that these have been a relatively flexible margin for adjustment. But as expenditures for wild horses in BLM holding facilities eat up more and more funds, the pressure to find a pragmatic solution will build. Taxpayers and the health of western rangelands stand to benefit from such a solution, though perhaps not as much as the wild horses themselves.

Fitzgerald and Rucker’s research paper “You Can’t Drag Them Away: An Economic Analysis of the Wild Horse and Burro Program,” coauthored with Vanessa Elizondo, was recently published in the Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics.