In the 20th century, people realized that energy sources such as coal and gas imposed costs on the environment. Trying to understand how to deal with emissions, they began to ask questions about balancing our energy needs with our desire for clean air and water. The desire to strike this balance became known as “sustainable development,” now a growing movement gaining even more traction in society today.

But what does sustainability really mean? Harlem Brundtland and the Brundtland Commission introduced the concept in 1987, defining it as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Two decades later, the World Conservation Union revisited the definition, suggesting that it had been vague, but “cleverly captured two fundamental issues, the problem of the environmental degradation that so commonly accompanies economic growth, and yet the need for such growth to alleviate poverty.”

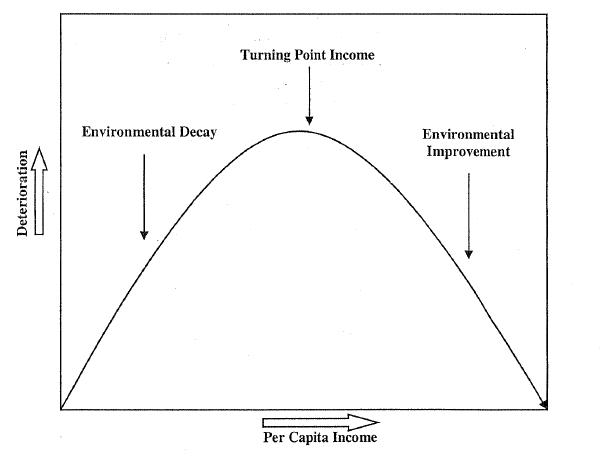

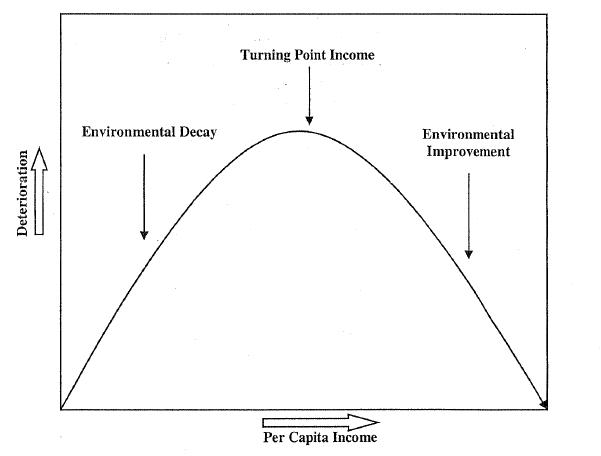

During this same period, economists were observing “a systematic relationship between income changes and environmental quality.” This relationship, known as the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) revealed that important indicators of environmental quality improved with rising incomes. In other words, they were observing economic growth and environmental improvement happening in tandem. The wealthier we get, the more environmental quality we demand.

As Bruce Yandle and his co-authors observed in their primer on the Environmental Kuznets Curve, while “there is no single EKC relationship that fits all pollutants for all places and times,” it does suggest a certain inevitability of environmental degradation with industrialization, followed by environmental improvement with increased wealth. There is an important exception they observed in 2002:

By way of contrast, there is no evidence to support the EKC hypothesis for gases such as carbon dioxide, which cause no harm locally but may affect the global climate as they accumulate in the atmosphere. The very nature of the potential harm—impact on global climate—makes unilateral action fruitless.”

As concerns about climate change continue to shape the way we think about economic development and environmental protection, resiliency may be more important than sustainability. Given uncertainty and constant change, resiliency is important to sustainability as “the capacity of a system to service, adapt, and grow in the face of unforeseen changes, even catastrophic incidents.” Whether or not we know exactly what sustainability means, we know economic and ecological resilience will help the world face environmental challenges.

Adaptation is a realistic approach to address growing concerns such as climate change, drought, and other issues. Today is Sustainability Day, a day to think about what sustainability can mean.

Can resilience help us adapt to climate change?

Free market environmentalism, Terry Anderson explains, is about respecting each other’s rights as we plan for the future. What is more sustainable than that?