45 years after the Endangered Species Act was enacted, it is as popular and as controversial as ever. Its popularity is easy to understand. Most everyone supports the values the statute represents, like protecting wildlife. The controversy, however, is more nuanced. There is a long running debate over whether the law is a success, because only 1% of species protected by it have gone extinct, or a failure, because only 2% of those species have recovered.

The answer, of course, could be that it’s a little of both—that the regulations imposed under the statute are effective at protecting the most vulnerable species from extinction but not at incentivizing active recovery efforts.

This week, I participated on a Heritage Foundation panel to discuss a new paper by Heritage’s Rob Gordon questioning how many of the statute’s celebrated recoveries truly were recoveries, rather than mere data errors. (The video for that event is embedded at the end of this post.)

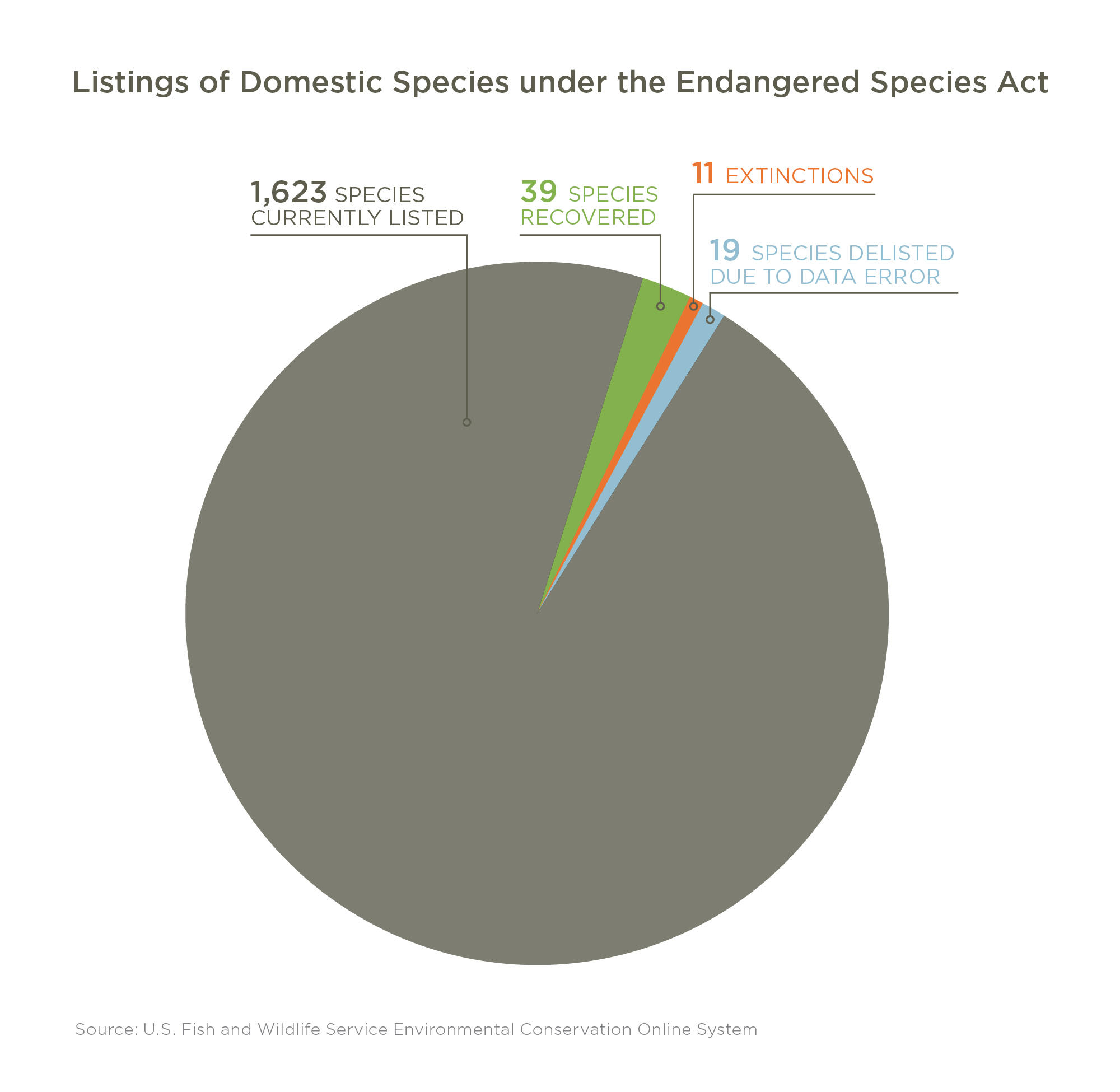

According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Endangered Species Act has resulted in only 11 extinctions in the United States but also only 39 species recoveries (as reflected in the chart below, which is taken from this PERC report).

Rob Gordon argues that this is too rosy an assessment. Although the statute has succeeded at preventing extinction, it’s even worse at recovering species than we thought. He argues that 18 of the 39 species claimed to have been recovered by the Endangered Species Act were actually never endangered. Rather, the listing of those species was due to data error: the population estimate at the time of listing was wildly off and more complete surveys showed that the species were plentiful. This means that the number of species delisted due to data error dwarfs the number recovered.

How can that be? Part of the explanation is the Endangered Species Act’s listing process creates odd incentives to list species based on uncertainty rather that first learning about them. Removing species from the list, in contrast, requires clearing a very high hurdle, which can only be done by developing the scientific information required to understand a species’ true status.

That could explain the number of errors, but what explains the persistently low recovery rate? The most likely explanation is also incentives. There’s a mismatch between who enjoys the benefits of regulation and who bears the cost. Many supporters of the Endangered Species Act bear little to no cost for it, and thus have less incentive to focus on whether the costs incurred are returning any real value.

Solving this trade-off problem requires greater reliance on markets to provide environmental benefits. When consuming goods provided by the market, you both enjoy the benefits of your choices and bear the costs of them. Thus, you’re unlikely to long accept a situation where you pay high costs but don’t receive the promised benefits. If you go to a restaurant, for instance, and the food is horrible, you probably won’t go back. But when something is provided to you for “free”—meaning the cost is borne by someone else—you will be less concerned with whether the benefits to you outweigh the cost to them.

A new PERC report, The Road to Recovery, offers one way to shift the way we protect species in a more market-oriented direction. As written, the Endangered Species Act distinguishes between “endangered” and “threatened” species, based on the degree of threats they face. The strictest regulations are reserved for endangered species, where they have generally worked to prevent extinction, but Congress intended to preserve more flexibility to experiment with innovative programs to recover threatened species.

The distinction between the two categories has been eroded by a 1975 regulation imposing the same regulations on all listed species, regardless of their prospects. A return to the statute’s original design would allow states to experiment with more market-based conservation programs. It would also make it easier for property owners and conservation groups to bargain over habitat protection and restoration, allowing them to better resolve trade-offs. The result could be a dramatic increase in the recovery rate for rare species, without sacrificing the Endangered Species Act’s success at preventing extinction.