If you are planning to visit a national park this summer, don’t be surprised by the higher entrance fee. On April 13, the Department of Interior, home of the National Park Service, announced that it would increase entrance fees for 117 parks from $30 to $35 per car per week.

This modest increase came after fierce opposition to Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s proposed plan, announced in October 2017, to raise fees to $70 per car per week. His fee would have applied to the busy summer season in only 17 of the crown jewels in the park system such as Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Grand Teton. The park service estimated that raising fees to $70 would have raised an additional $70 million, which would have been used to help fix the crumbling infrastructure at the parks. Zinke backed down from $70 and reduced the fee increase to $35 in response to the fierce public outcry. Montana Senator Jon Tester (D) expressed the opposition from his constituency claiming that “doubling entrance fees would have priced too many Montana families out of our public lands.”

With the new fees, a family of four driving through the Teddy Roosevelt Arch into Yellowstone and staying seven days will be paying just $5 per day, up from $4.25 per day when the fee was $30 per week. If the family planned to visit several national parks during the year, it could get the price per visit even lower by purchasing the America the Beautiful Annual Pass for $80. And senior citizens can purchase the lifetime Golden Age Passport for $80, which Zinke raised from $10 last August, despite objections from AARP.

But if the national parks are “America’s best idea,” as Ken Burns and Dayton Dutton called them in their popular PBS documentary, shouldn’t we be willing to pay for them? After all, families pay well over $35 for a couple of hours of entertainment at the movie theater, and a visit to Disneyland will cost a family of four, with both kids over 10, $1,280 for five days. National parks, by comparison, are a bargain.

If you visit state parks, which generally are much smaller and less spectacular, you’ll find fees comparable to Zinke’s original proposal. In California, entrance fees are $10 per car per day—$70 per week. Arizona’s daily fee is $7 per vehicle for up to four passengers. In Maine, adult residents pay approximately $5 per day and non-residents $7.

Foreign national parks are even more expensive. Canada’s Banff National Park in Alberta will cost you over $15 per vehicle per day. Addo National Park in South Africa, with some of the largest elephant herds in Africa, charges $23 per day for foreigners. The foreigner’s entrance fee at Kenya’s Masai Mara, famous for the massive wildebeest migrations, is $80 per adult per day and $45 for children under 12. In contrast to the high fees for foreigners, Addo National Park charges only $6 for South African citizens, and Masai Mara charges $12 for Kenyan citizens.

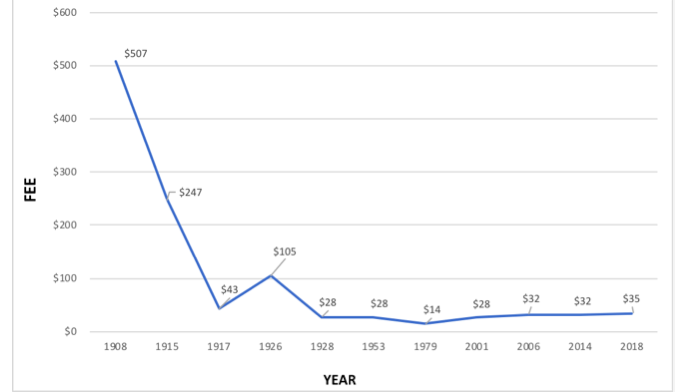

Putting entrance fees in a historical perspective, the inflation-adjusted fee for driving into Mt. Rainier National Park, the first to charge an entrance fee, was over $500 in 1908. For Yellowstone, it was nearly $250 in 1915. Those fees fell rather precipitously by the 1920s to around $25 in today’s dollars, where they more or less remained until the recent increase. Over the same period, per capita incomes in the United States rose more than 75 fold. It seems highly unlikely that national park entrance fees of either $35 or even $70 will price citizens out of their public lands.

So, where does opposition to higher fees come from? Like so many ideas in Washington, it comes from special interest groups who do not want to lose the benefits of the status quo. In this case, those groups include gateway communities, park concessioners, and the outdoor recreation industry. They understand that the money visitors spend at the park gate for entrance fees is money not spent on lodging, food, tours, backpacks, and souvenirs. As Senator Tester puts it, higher fees will cause visitors to “empty their wallets” and “undercut our state’s thriving outdoor economy.”

Another source of opposition is Congress itself. Politicians hate to lose their control of agencies by giving them more discretion. This is not a new problem. As director of the newly created National Park Service in 1916, Stephen Mather saw revenues from fees as a way of funding the parks. In the early years of the park service, receipts from entrance fees and concessioner rents exceeded expenditures in parks such as Yellowstone and Yosemite. Those surpluses went into a special Treasury account controlled by the director. New York Congressman John Fitzgerald, however, believed that expenditures should be approved by the House Interior appropriations subcommittee. In 1918, he succeeded in having all park receipts transferred to the general Treasury.

The congressional stranglehold on park budgets continued until 1996, when, in a rare instance, Congress gave more discretion to the National Park Service by passing the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act. This act allows parks where fees are collected to retain 80 percent of the revenues and the park service to allocate the remaining 20 percent across the system as needed. In response, however, Congress offsets much of the fee revenue by reducing congressional appropriations for park operations. As a result, between 2005 and 2015, when the federal budget grew by nearly 40 percent, park budgets grew by less than 2 percent. Meanwhile, park attendance grew to a record of 305 million visitors.

Imagine how things would change if national parks really were self-sufficient. Yellowstone could cover all of its operations with a fee of $12 per visitor per day and Glacier with $8. Assuming that the average car paying $35 per week carried four passengers, the present daily cost is $1.25 per visitor per day. Charging fees that would cover costs would give the park service an incentive to collect fees and, if local park managers had the discretion, to spend the funds where they are most needed, be that on visitor services or infrastructure.

As implied above, charging higher fees to non-taxpaying foreign visitors is another way to generate more revenue, and this would not “nickel and dime Montana families” as Senator Tester put it. Nearly 15 million foreigners visited U.S. national parks in 2017. It they each paid $80, the fee for the Masai Mara, foreigners would contribute another $12 million for park operations each year.

The U.S. parks could take another page from foreign parks by seeking corporate sponsorship. These needn’t be ads painted on the rock wall in Yosemite or banners hung from the rims of the Grand Canyon. In Addo Elephant Park in South Africa, for example, there are two signs at the main entrance: one is a tasteful sign in front of the thatched roofed gate stating entrance fees; the other gives the name of the energy company sponsoring Addo. Rhino Arch, a non-profit in Kenya, built a 400-kilometer electric fence to reduce conflict between elephants and subsistence farmers with funds raised from corporations who get credit for their conservation ethic.

The sky is the limit as to how much might be raised from corporate sponsorship and charitable foundation donations in the United States. To honor the 100th birthday of the National Park Service in 2016, the National Parks Foundation, a congressionally authorized non-profit created to support parks, launched a campaign to raise $250 million for improving trails, visitor centers, and other park infrastructure. So successful was its campaign that the goal was raised to $500 million, and it has already been achieved.

In addition to operating costs, national parks face a backlog of infrastructure repairs and upgrades estimated to cost $11.6 billion. As Shawn Regan, research fellow at the Property and Environment Research Center, told the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, visitor centers are in a sad state of repair, 40 percent of park roads are rated as “fair” or “poor,” and dozens of bridges are considered “structurally deficient.”

The extra $60 million that the park service estimates will come in from $35 fees would only be a drop in the bucket of infrastructure backlog. However, if the national park system covered all of its operating costs out of user fees and corporate sponsorships, it would free up nearly $3 billion per year that could go toward the $12 billion maintenance backlog.

Secretary Zinke’s willingness to think outside the box is a breath of fresh air in Washington, and there is hope that it might catch on in Congress. Rob Bishop (R-Utah), chairman of the House Committee on Natural Resources, said the modest increase in fees “moves us towards more of a ‘user pays’ system which is positive.” Unfortunately, his preface to that comment—“any change to user fees should be approved by Congress”—suggests we are still a long way from taking parks out of politics and politics out of parks.

The article was originally published in Defining Ideas, a Hoover Institution Journal.