“The Endangered Species Act is the pit bull of environmental laws,” Edward Poitevent tells me over shrimp po’boys in a cafe not far from his family’s land in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana. “Once it gets ahold of you, it doesn’t let go.”

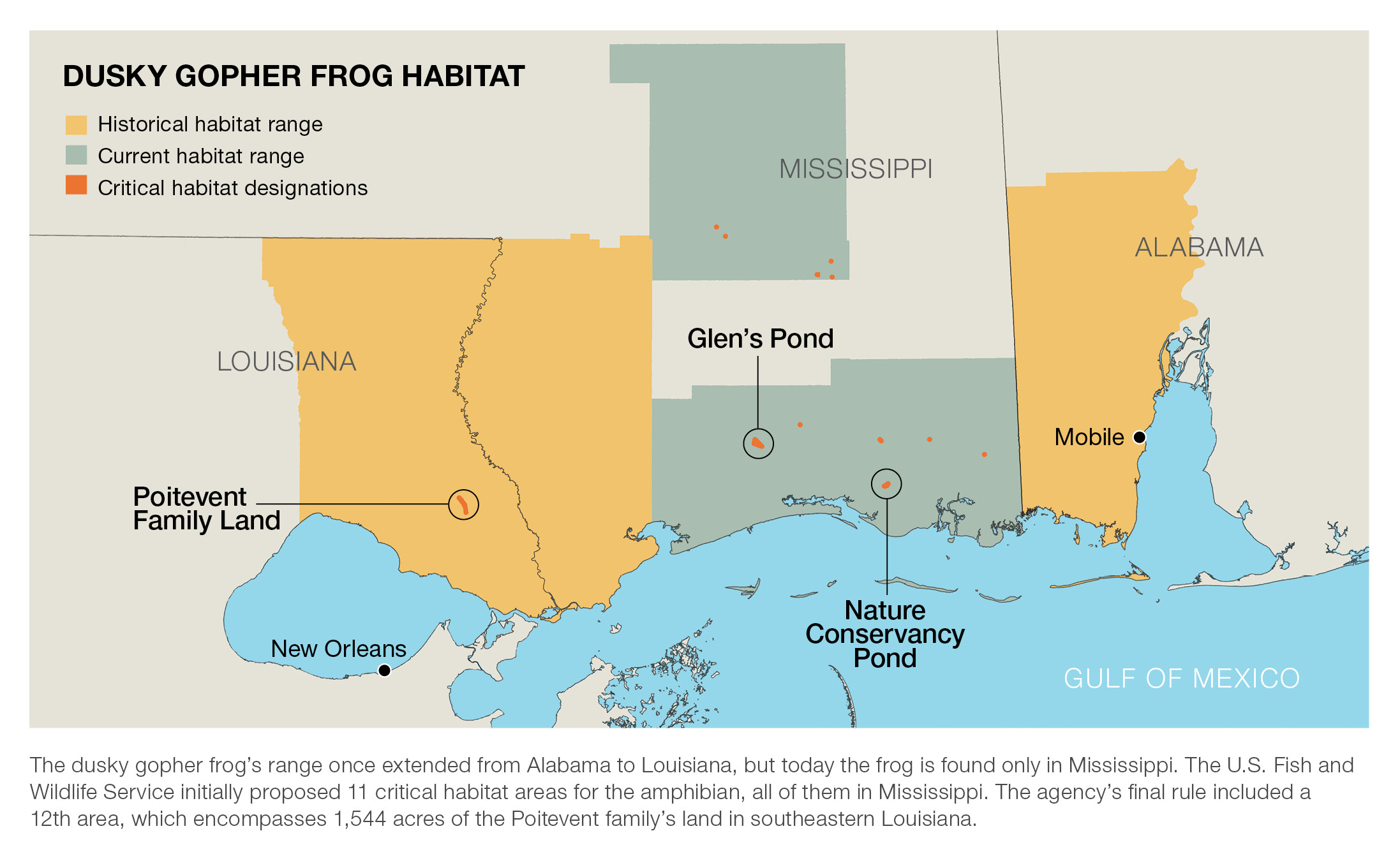

Poitevent should know. The law first nipped at him in 2011, when he got a phone call from two U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists one Friday afternoon. They informed him that roughly 1,500 acres of his family’s property had been designated as critical habitat for the endangered dusky gopher frog, a species that hasn’t been documented in his state for half a century. The agency designated the area despite the fact that the land cannot support the frog without significant changes to it—changes that the landowners say they have no intention of making.

Over the course of seven years, the statute has managed to drag Poitevent all the way to the Supreme Court, which will hear his case in the fall. It will answer the question that has dogged him since he received that phone call: Can land that is uninhabitable by an endangered species be designated as critical habitat for that species?

Long Lost Pines

Longleaf pine savannas once covered 90 million acres across the American South. Fires caused by lightning or set by Native Americans constantly rejuvenated these landscapes, spawning a grassy layer that provided lush habitat for countless species. Today, only about 2 million of those longleaf acres remain. Development and construction are partially responsible, but commercial timber production is the main reason. As long-standing longleaf forests were harvested, timber companies and landowners replaced them with dense plantations of faster growing species like loblolly and slash pine.

Poitevent’s land in St. Tammany Parish is a typical example of this long-term forest transition. The parcel designated as critical habitat is part of a 45,000-acre tract owned by the family and leased by timber giant Weyerhaeuser. The loss of southern longleaf forests has been a boon to generations of Americans from New Orleans to Norfolk who have benefited from the subsequent development. But it’s been mostly bust for the dusky gopher frog, which relies on longleaf savannas for survival.

The amphibian’s historical range stretched along a coastal plain from the Mobile River delta in Alabama, across southern Mississippi, and into southeastern Louisiana. That area contained longleaf ecosystems with the three elements the species requires: so-called “ephemeral” wetlands where the frogs breed, upland forests with open canopies where the frogs live, and habitat that connects the two. The frog spends most of its time in stump holes and tortoise burrows, but shallow ponds that dry up seasonally—and can’t support fish that would prey on its larvae—are crucial. Periodic fire is also necessary to maintain all three elements. Burning rejuvenates the grasses that provide cover for the frogs and vegetation to which they attach egg masses in the seasonal ponds.

Today, the dusky gopher frog is found only in Mississippi. In 2011, when the Fish and Wildlife Service initially proposed the critical habitat designation for the frog, it only included areas in Mississippi. But as the agency later noted, biologists enlisted to review the proposal indicated that it “was inadequate for the conservation of the dusky gopher frog” and recommended a reassessment to include the species’ historical range in Louisiana and Alabama.

Even as the Fish and Wildlife Service deemed the Poitevent land “essential” to conserving the frog, the agency’s final rule conceded that “the surrounding uplands are poor-quality terrestrial habitat for dusky gopher frogs” given that they lack the open-canopied longleaf ecosystem the frog requires.

Under the Endangered Species Act, critical habitat is supposed to encompass areas that have physical or biological features essential to conserving a species. But the act also provides room to include “specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed” if the Interior Secretary determines them to be “essential for the conservation of the species.” In the case of the dusky gopher frog, the Fish and Wildlife Service determined that a farther-reaching habitat designation was needed as a hedge against extinction. With all existing frogs concentrated in southern Mississippi, the agency worried that a catastrophic event like a region-wide drought could wipe out the species.

Poitevent contends that government biologists then trespassed on his land to scope it out during the reassessment. Regardless, the agency determined that five ephemeral ponds exist in the area. It ultimately included 1,544 acres of Poitevent’s family property in its final designation due to “the importance of ephemeral ponds to the recovery of the dusky gopher frog.” Yet even as it deemed the Poitevent land “essential” to conserving the frog, the agency’s final rule also conceded that “the surrounding uplands are poor-quality terrestrial habitat for dusky gopher frogs” given that they lack the open-canopied longleaf ecosystem the frog requires.

Craving Diversity

“I like to say that out here the diversity is from the knees down,” says Becky Stowe, director of forest programs for the Nature Conservancy in Mississippi. We’re standing in front of one of those all-important ephemeral ponds on the conservancy’s 1,700-acre property in Old Fort Bayou, 60 miles east of the Louisiana border. She’s referencing the diverse layer of grasses and small shrubs that cover an open landscape sparsely dotted with pine trees. Small orange flags are scattered throughout the pond, full from spring rains, marking the locations of this year’s dusky gopher frog egg masses.

The Nature Conservancy acquired the site from a timber company in 2002 and turned it into a wetland mitigation bank, selling credits to developers to compensate for loss of wetlands elsewhere. The Fish and Wildlife Service approves such banks to promote conservation of species that are “endangered, threatened, candidates for listing, or are otherwise species-at-risk.” The aim at Old Fort Bayou was to protect the endangered Mississippi sandhill crane, of which only about 100 remain. But it didn’t take long for it to become a dusky gopher frog recovery site.

By 2004, the frog had dwindled to two known populations, both in Mississippi, and one appeared to be dying out entirely. The principal breeding site, a pond in De Soto National Forest known as Glen’s Pond, was home to just 100 to 200 adult frogs. That year the Nature Conservancy started a project with the goal of establishing a new population at Old Fort Bayou.

Given the frog’s particular habitat requirements, it wouldn’t be easy. The organization would not only have to recreate a longleaf savanna ecosystem by thinning existing stands in certain areas, planting new ones in others, and managing the landscape with prescribed fire. Biologists would also have to establish a frog-rearing station that allowed them to release enough of the amphibians to give them a chance at survival in the wild.

In coordination with the Fish and Wildlife Service, biologists initially obtained tadpoles from the existing frog population and raised them in cattle tanks, feeding them algae wafers once a week. Today, at a Nature Conservancy lab housed at the Camp Shelby military training site south of Hattiesburg, the frog-breeding effort is more sophisticated. The process starts with collecting dusky gopher frog eggs from the wild. Nature Conservancy biologist Jim Lee and two technicians then raise the frogs in 284-liter aquariums, where they benefit from better filtration and aeration. The lab also raises gopher tortoises, a species listed as threatened in Mississippi. Their burrows provide homes for 300 other species, including gopher frogs.

Amidst a room of tanks and heating lamps and plastic tubs, Lee describes the operation as a “head start” for the frogs. His team has worked hard to figure out the most efficient way to raise eggs and tadpoles into full-grown frogs that can cut it outside of captivity. But the frog rearing is clearly a lot of work. And in the case of the dusky gopher frog, it’s all for a slimy amphibian that few Mississippians, let alone other Americans, are ever likely to see. Why should most of them, who probably don’t share Lee’s affinity for amphibians and reptiles, care about preserving the frog?

“What if we all only had one movie to see or one food to eat?” Lee asks in response. “Diversity is something we all crave and desire.” Lee also makes what is perhaps a more salient point for most people: The frog’s decline is “100 percent” due to humans, and he feels that his own species has a responsibility to do something about that, or at least have some sympathy for the amphibious species.

The frog has expanded from the one breeding population in 2004 to six today, according to biologists with the Nature Conservancy. At the Old Fort Bayou pond, the organization has released nearly 3,800 tadpoles and more than 5,500 “metamorphs”—or full-fledged frogs—over the years. This spring, there were 28 orange flags marking egg masses in the pond. Based on evidence from male frog calls, which are invariably described as “snoring,” the biologists estimate there are perhaps 20 males. That means fewer than 50 adult frogs have survived at the site—a testament to the difficulties of recovering the species.

While the effort has established a frog population at Old Fort Bayou, it’s still an uphill road for the dusky gopher frog. In its final recovery plan released in 2015, the Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that there may only be 135 of the frogs left in the wild. And as difficult as it’s been to turn 9,000 tadpoles and metamorphs into a viable population at Old Fort Bayou, maintaining the landscape necessary to support the frogs may be even more work.

One of the biggest challenges is the need to maintain the longleaf pines, which historically rely on fire. To that end, the Nature Conservancy conducts controlled burns on its property throughout the growing season. The fire crew requires a minimum of six people and is wholly reliant on weather, wind patterns, and the magnanimity of neighbors, one of which is a golf resort. The organization’s biologists also note the need to remove mosquitofish from frog ponds that don’t dry out completely every year.

Looking back over the longleaf prairie, Stowe emphasizes the amount of effort required to maintain this landscape. She also recognizes the unique position and mission of her organization, which enable it to navigate the costly federal approval processes that are needed to work with endangered species and carry out the project. But she also adds: “It’d be cool if private landowners could do something like this and get credit for it—or at least not get penalized for it.”

Suitable Habitat

The reason critical habitat designations can be so controversial are the ramifications they can have on how the land can be used. If a designation includes private property, then anything requiring a landowner to obtain a federal permit—which in the case of wetlands can apply to activity as straightforward as excavating and moving dirt—requires “consultation” between the landowner and the Fish and Wildlife Service. The agency notes that only activities that “are likely to destroy or adversely modify critical habitat” are affected. It also says that it works with landowners to “amend their project to enable it to proceed without adversely affecting critical habitat.” The handbook that details the consultation process runs more than 300 pages.

In Edward Poitevent’s case, the designation of 1,544 acres of his family’s property may not affect much immediately, given that timber harvesting generally doesn’t entail the federal “nexus” that would trigger consultation. But he and his family have forward-looking plans for the land, which happens to be in what has been described as “the boomingest corner of the state.” In the mid–2000s, the landowners struck an agreement with Weyerhaeuser’s real estate arm to jointly develop the land, working to rezone the area for a mix of residential, commercial, and open space. The critical habitat designation puts those development plans in jeopardy.

The Fish and Wildlife Service stated in an email from a public affairs officer that it does not comment on pending litigation. But the agency’s economic impact analysis examines a range of possible outcomes if consultation were triggered. The most restrictive scenario would “recommend complete avoidance of development” of the 1,544 acres. Under that no-development scenario, the agency estimates the landowners would lose out on $34 million in potential development value, based on market prices of comparable land in the area.

Collette Adkins disputes that valuation. “If that land was so highly prized for development,” she says, “then it would already be developed.” Adkins is a senior attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity, which will defend the government’s critical habitat ruling at the Supreme Court. She also claims that the Fish and Wildlife Service rarely stops projects entirely but would be more likely to recommend changes to development plans to protect species. She points to two agency programs—habitat conservation plans and safe harbor agreements—that allow landowners to continue using their land while still providing protections for endangered species.

Adkins disputes Poitevent’s claim that the habitat designation imposes severe costs with no real benefit to the species. She says the land doesn’t have to be ideal for the frog for it to play a conservation role. “It really just comes down to the landowner’s willingness,” she says. “I do understand that someone like him has a very strong private property rights perspective. But for me, because I think I have a different value set, it’s not a penalty, it’s an opportunity to save an endangered species.

“I just think it’s a mindset that comes from his values,” she says. “That would be very different if it were a different landowner.”

Poitevent certainly doesn’t see it that way. To transform the tract in St. Tammany Parish into dusky gopher frog habitat as defined by the Fish and Wildlife Service, the landowners would essentially have to replicate the Nature Conservancy’s efforts at Old Fort Bayou. That would require logging the existing commercial pines, planting longleaf pines, and maintaining the landscape with prescribed fire. It would also likely mean collaborating with biologists to obtain and release a multitude of frogs at the site.

“Our land is not suitable for the frog,” says Poitevent. “We know that. The government and Fish and Wildlife Service have said that you don’t have the elements for it. So to make it suitable you’d have to rip up every tree on 1,544 acres, replant all of it with the right tree, make sure the ponds are still there, and make sure you burn it every year. Who is going to pay for that? They don’t care. It’s not their job. Their job is to find a habitat. The consequences are not their problem.”

Lawyers or Biologists?

In its final rule, the Fish and Wildlife Service notes that in addition to Louisiana it went back and examined portions of Alabama for additional dusky gopher frog habitat. It found a single record, from 1922, describing habitat for the frog at a location near Mobile Bay. “The upland terrestrial habitat at this site,” the rule reads, “has been destroyed and replaced by a residential development.” So in a respect, the Endangered Species Act seems to be punishing a landowner in Louisiana for leaving land undeveloped. If the Poitevents had cleared their property in St. Tammany Parish to build houses 20 years ago, there presumably would be no Louisiana habitat case to bring to the Supreme Court today.

The reality is that many endangered species disputes may not really be about conservation—the act can be a powerful attack dog to stop development in its tracks whether it helps a species or not. But given the law’s dismal recovery record of listed species, it’s worth asking whether critical habitat designations actually promote recovery—and what reforms could help do more than prevent extinction.

It may also come down to a question for groups involved in endangered species conservation: Do you hire lawyers or biologists? The Center for Biological Diversity—which, to be clear, has scientists as well as attorneys on staff—was involved in the original petition to list the frog as endangered in 2001. It was also the party that sued the Fish and Wildlife Service in 2007 for not making a habitat designation in a timely manner. As part of the settlement, the agency paid plaintiff legal fees of nearly $10,000. The fact that the Endangered Species Act provides for the reimbursement of such legal fees gives a clear incentive. And as demonstrated by the Nature Conservancy’s ongoing efforts to give the dusky gopher frog a few more footholds in coastal Mississippi, the biologist track isn’t for the faint of heart.

The great shame is that regardless of the Supreme Court’s ruling, it seems the frog will not benefit one iota.

So far, the lower courts have deferred to the Fish and Wildlife Service’s authority in designating the frog’s critical habitat. In its argument that the Supreme Court need not take up the case, the Center for Biological Diversity asserted that the agency had done its “requisite economic analysis” and that the landowners “ignore the benefits of the frog’s critical habitat designation, and their claims regarding the economic impact of the designation have no basis in reality.” The latter point seems to allude to the fact that the landowners “would experience no economic impacts if they continued to use the land as pine plantations,” as the center worded it later in its brief.

That point raises a fundamental question: If even the party who initially sued for the sake of the dusky gopher frog acknowledges that the outcome of the nation’s highest court could have virtually no bearing on the frog’s conservation prospects, what’s been the point of the last seven years of acrimony and litigation? The great shame is that regardless of the Supreme Court’s ruling, it seems the frog will not benefit one iota. The Louisiana landowners don’t have the inclination nor the resources to establish proper frog habitat, and the government admits its authority to designate habitat cannot compel anyone to take any further steps toward species recovery.

The Fish and Wildlife Service’s final rule notes that its economic analysis “did not identify any disproportionate costs that are likely to result from the designation.” Poitevent counters that “only a government that has $20 trillion in debt and is run by unaccountable, unelected bureaucrats could declare $34 million to be insignificant.” His side’s legal argument characterizes the agency’s stance on his family’s land as “potential backup habitat” for the frog, essentially a safeguard for the species in case a catastrophe were to wipe out the Mississippi population.

“They don’t use that phrase exactly,” Poitevent says, “but that’s what it is. But so is your backyard. You’re not gonna spend enough money to turn it into frog habitat,” he continues. “So how does this benefit the frog? It doesn’t, and it won’t. Yet all they tell you is they need our land to save the frog.

“The point is that they all along have said, ‘Too bad, this land is ours now, it’s out of commerce. Who’s gonna buy it from you? Nobody. And we’ve already determined that you can’t develop it,’” referring to what he believes would be a foregone conclusion of consultation with the agency. “How fair is that?”

The Supreme Court will hear the case during its October term. Poitevent expects to know his fate by the end of the year. The decision of the nine justices may not have much bearing on the fate of the dusky gopher frog. But whatever the legal outcome, the Nature Conservancy will keep burning the landscape, restoring longleaf habitat, and raising dusky gopher frogs in its quest toward recovery.