DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

Widespread attention to so-called “conflict minerals” has led many consumers to ponder whether the metals contained inside their mobile phones or laptops have fueled civil wars and violence in far-flung places. In the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a principal source of such minerals, armed groups have been prevalent in mining, often controlling the trade in valuable minerals.

Congress passed legislation in 2010 that aimed to ensure purchases of such minerals would not fund violent militias. Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act tried to accomplish this aim by requiring U.S. companies to disclose the provenance of tin, tungsten, and tantalum that they purchased. The policy’s architects hoped that the disclosures would cut off funding to militias who brutalized locals, thereby reducing the suffering of people in affected communities.

In this PERC Policy Series, economist Dominic Parker summarizes two recent academic studies in which he and coauthors examined the effects of the policy and whether it achieved its aims. While the conflict-mineral measures may have reduced militia funding, the evidence suggests that they had the unintended effect of increasing human suffering. Parker finds that the legislation largely backfired, raising infant mortality in certain villages and also increasing militia violence against civilians. He concludes by briefly examining how alternative approaches could have bolstered human rights and economic opportunities in the eastern Congo.

This paper is part of the PERC Policy Series of essays on timely environmental topics, published by the Property and Environment Research Center, a nonprofit research center located in Bozeman, Montana, that explores market solutions to environmental problems. instead of negotiation and cooperation.

Reviews

Professor Parker’s research provides one of the most comprehensive and important insights regarding the plight of the Democratic Republic of Congo since the passage of Dodd-Frank Section 1502. This paper is an exceptionally valuable resource that summarizes his in-depth work. The writing style is very accessible, rendering this paper very useful for policymakers, academics, and everyday consumers.

—Karen E. Woody

Assistant Professor of Business Law & Ethics, Indiana University, Kelley School of Business

We may know that the road to hell is paved with good intentions, but we rarely see such powerful evidence for this than in the brilliant work of Parker and co-authors. They show that crude policies to control violence are no match for the strategic responses of the sophisticated actors whose behavior the policies seek to control. As a consequence, the policies not only fail to improve the welfare of people living on the precarious edge but may—and did in the Congo—exacerbate human misery.

—Philip Keefer

Principal Economic Advisor, Institutions for Development, Inter-American Development Bank

The unintended consequences of well-meaning interventions by wealthy countries in developing economies are seldom subject to such serious and penetrating analysis. This excellent report should be required reading for policymakers and the foreign aid community.

—Mary M. Shirley

President, Ronald Coase Institute

Introduction

In recent years, there has been increased attention on so-called “conflict minerals” and whether trade in them has fueled civil wars and violence. The minerals are essential components of mobile phones, tablets, and similar electronic devices, and the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is a principal source of them.

Amidst growing concern, Congress passed legislation in 2010 that aimed to ensure purchases of such minerals were not funding armed groups. The measures were introduced as Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act and required companies to disclose the source of their purchases of tin, tungsten, and tantalum—the primary minerals in question. The measure aimed, to quote co-sponsor U.S. Rep. Barney Frank, to “cut off funding to people who kill people.1

Human rights advocacy groups supported the bill as a positive step. The logic was that minerals in the DRC were mined under the control of armed militias who brutalized locals, and purchases from these sources fueled such violence. In response, Dodd-Frank tried to coax large companies like Apple and Intel, whose products contain the minerals, to declare their provenance. The hope was that the regulation would reduce funding to militias, thereby reducing the suffering of people in affected communities.

Now, several years removed from the legislation taking effect, we can examine whether it achieved its aims. This PERC Policy Series assesses the on-the-ground impacts by summarizing two recent academic studies in which coauthors and I examined the effects of the policy, along with related research. The record suggests the conflict minerals measures backfired, at least through 2015. Specifically, the legislation had the unintended effect of more than doubling infant mortality in villages near mining sites. Moreover, it also appears to have increased militia violence, rather than curbing it.

These unwanted consequences were a result of two main forces. First, Section 1502 initially caused a widespread, de facto boycott on minerals from the eastern DRC. Rather than engaging in costly due diligence to identify the sources of minerals—and risking being considered a supporter of rebel violence—some U.S. companies simply stopped buying minerals from the region. This de facto boycott had the intended effect of reducing funding to militias, but its unintended effect was to undercut families who depended on mining for income and access to health care. The decreases in mineral production rocked an artisanal mining sector that had supported an estimated 785,000 miners prior to Dodd-Frank, with spillovers from their economic activity thought to affect millions.2

Second, the legislation changed the relative value of controlling certain mining areas from the perspective of militias, who changed their tactics accordingly. Before the boycott, the militias maximized revenue by taxing tin, tungsten, and tantalum at or near mining sites. They therefore had an interest in keeping mining areas productive and relatively safe for miners. After the legislation, the militias sought to make up for reduced revenue in other ways. According to the evidence, they started to loot nearby civilians who were not necessarily involved in mining. They also started to fight for control over other commodities, including gold, which was in effect exempt from the regulation.

In short, the Dodd-Frank Act disrupted an informal arrangement that was far from perfect, yet somewhat stable, and replaced it with a dangerous and chaotic environment in which armed groups violently sought new sources of revenue. The account sheds light on the deadly, if unintended, consequences of conflict-mineral regulation and alternatives that could have potentially achieved the aim of reducing militia activity without harming local civilian populations.

Background

The DRC contains large deposits of tin, tungsten, and tantalum—the so-called “3Ts”—valuable minerals mined for use in the manufacturing of phones, laptops, and other modern electronic devices. In recent years, armed militia groups have controlled a portion of the production of 3T minerals, along with gold, in the eastern DRC by taxing and extorting miners. The eastern provinces usually associated with conflict minerals are North Kivu, South Kivu, Maniema, Orientale, and Katanga.3

Artisanal miners who work informally and independently control the majority of the mines in the eastern DRC. These miners use minimal technology and a labor-intensive process as they pan and dig for alluvial, open pit, and hard-rock mineral deposits. In the years prior to Dodd-Frank, artisanal miners extracted an estimated 90 percent of the minerals exported from the country.4 Estimates of the number of artisanal miners in the five eastern provinces ranged from 710,000 to 860,000 in 2007.5

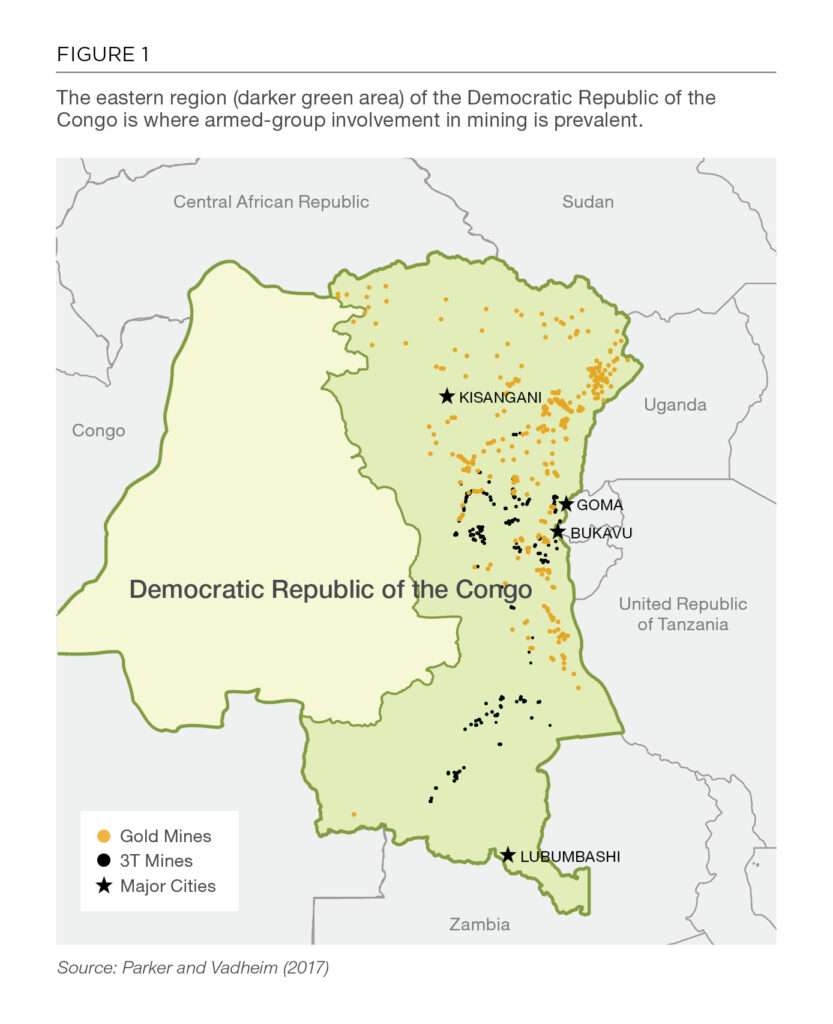

The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) mapped the locations of artisanal mining sites from 2008 to 2010, before the passage of Dodd-Frank. The maps revealed that gold and tin mines were most prevalent and tantalum and tungsten sites were relatively rare. Armed militias, usually consisting of young men, controlled or regularly visited approximately half of the mines, usually to tax and extort miners. Figure 1 shows the locations of mines in the eastern DRC before Dodd-Frank was passed.

Congress first attempted to regulate conflict minerals in April 2009, and a revised version of the original proposal became Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act, signed into law on July 21, 2010.6 The narrow goal may have been to cut off funding to armed groups, but the broader aim seems to have been to reduce human suffering in the DRC.7

Section 1502 of the law directed the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) to create disclosure rules for companies that make products containing tin, tungsten, tantalum, or gold.8 The rules require companies to conduct “due diligence” on the origin of the minerals in question. If minerals come from a conflict-mining zone, then the buyer must report on the possibility that militias benefited from the purchases. The SEC also authorized Congress to produce a map of the conflict-mining zone for the U.S. State Department to guide the regulatory process. Due to the extra scrutiny SEC regulators gave this mapped area, 3T mines located within it were evidently more likely to be boycotted.9

While Section 1502 did not prohibit companies from purchasing minerals that originate in conflict-mining zones, many observers agree that it acted as a de facto boycott of 3T minerals.10 Rather than incurring the costs and effort of verifying that mineral purchases did not finance armed militias, many U.S. companies decided not to buy 3Ts from the entire conflict zone. Furthermore, in conjunction with Section 1502, the DRC government imposed a ban on artisanal mining in three eastern provinces in September 2010.11 The DRC lifted its ban in March 2011, but by the next month the implicit boycott of minerals from the eastern DRC had became much more explicit. In April 2011, the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition, a group of electronics and tech companies, stopped buying 3Ts from smelters who could not prove their source minerals did not fund conflict.12 It is likely that Dodd-Frank directly encouraged this explicit international boycott, which effectively replaced the DRC government’s ban.13

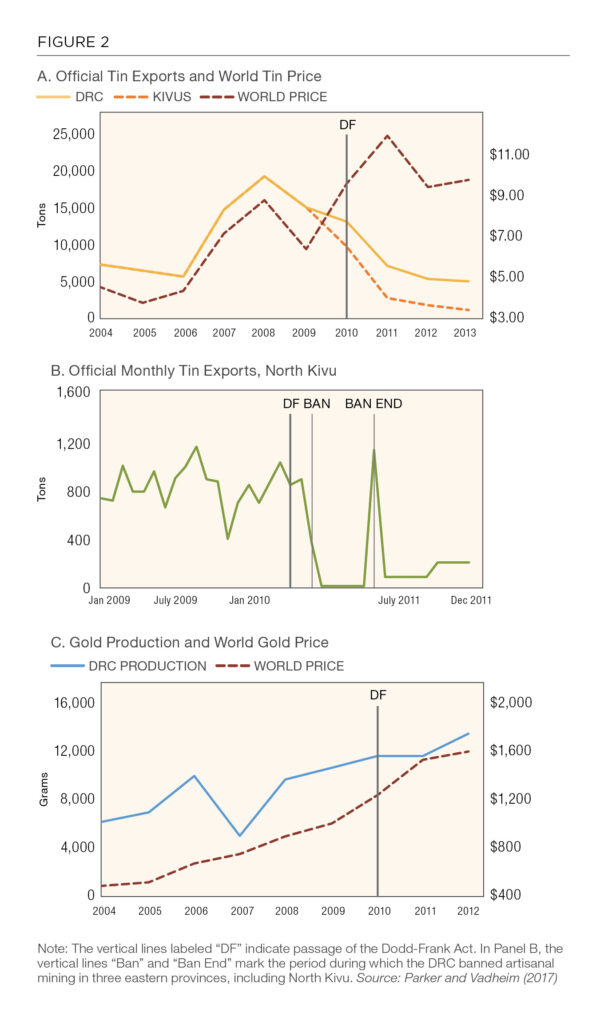

What effect did Dodd-Frank, the associated mining ban, and the explicit boycott have on mining activity? Official data reveal a substantial drop in exports of 3Ts from the conflict area after Dodd-Frank, followed by a rebound in exports over 2013-16.14 Figure 2 shows the decrease in tin exports from North Kivu, South Kivu, and Katanga shortly after Dodd-Frank. As seen in Panel A, the volume of official exports tracked the world price from 2004-09 but then dropped significantly during 2010-11, even as the world price continued to rise. Some of the decrease in exports from the mining zone targeted by Dodd-Frank was offset by increased exports from Katanga Province, which was exempt from the mining ban and largely outside the conflict territory mapped for the State Department. We also know that while official exports ceased during the ban, as seen in Panel B, some 3T mining did continue in the policy-targeted zone. Throughout the ban, a number of Chinese companies continued to buy 3T minerals from eastern Congo, but at heavily discounted prices compared to world market valuations.15

When it comes to gold, export data provide a less reliable indicator of production because virtually all gold mined in the eastern DRC is smuggled through unofficial channels.16 Panel C of Figure 2 plots estimates of gold production from 2004-12. Production generally rose, with a slight decrease when the mining ban was in force in 2011, but overall there is little evidence that Dodd-Frank reduced gold production.

Taken together, the data suggest that Dodd-Frank and the mining ban were effective at slowing 3T mining within the targeted conflict-mining zone but less effective at slowing gold mining. There are two main reasons why gold production rose despite its official status as a “conflict mineral” under Dodd-Frank. First, DRC gold mainly supplies jewelry markets in the Middle East and East Asia, whereas 3Ts primarily supply companies that are regulated by Dodd-Frank or members of the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition. Second, it is technologically feasible to track the origin of 3Ts and demonstrate whether they coincide with areas controlled by armed groups. The eastern DRC lacks smelting facilities to completely remove waste rock from 3T minerals, and the waste rock can help identify the origin. It is much more difficult to determine the providence of gold because it can be more easily smelted on site or earlier in the supply chain.

Artisanal mining was an important economic sector in the eastern DRC prior to Dodd-Frank but was dramatically disrupted by a boycott of purchases triggered by Section 1502. There are several pieces of evidence indicating the boycott slowed 3T mining within the Dodd-Frank targeted conflict-mineral zone. There is little to no evidence to suggest that 3T mining slowed outside the zone or that gold mining slowed anywhere. In addition, our research suggests that these mining policies had significant ramifications for infant mortality and militia violence in communities near artisanal mining sites.

Effects on Infant Mortality

In research published in the Journal of Law & Economics, economists Jeremy D. Foltz, David Elsea, and I assessed the infant mortality effects of Dodd-Frank using a data set constructed from publicly available sources, including Demographic and Health Surveys data.17 As of 2013, the DRC had the sixth highest infant mortality rate in the world, at 78 deaths per 1,000 live births.18 Across our study region of the eastern DRC, the number of infant deaths per 1,000 births changed from 87 in 2007 to 55 in 2009 to 72 in 2012.19

The Dodd-Frank legislation could have impacted infant mortality in the eastern DRC through three main channels: 1) conflict and violence, 2) family income and employment, and 3) access to health care services. On one hand, infant mortality could conceivably decrease due to Dodd-Frank if the legislation succeeded in achieving its goal of lowering civilian exposure to violent armed conflict. On the other hand, even if the law succeeded in reducing armed conflict—and we will see that it did not—it could have raised infant mortality by reducing income streams to families and communities dependent on artisanal mining and by disrupting mother access to health care facilities and services.

To measure infant mortality, teams with the Demographic and Health Surveys asked women to recall their complete birth history as well as the month and year of their children’s deaths. The data set also includes information on birth order, child gender, household size, and mother’s education and marital status at the time of the interview.

From this information, we created a mortality measure spanning births occurring from 2007-12. These births are linked spatially to the village of mother’s residence when she was interviewed for the survey. Each birth is coded as a statistical observation with an outcome equal to one if the child survived for 12 months and equal to zero if the child did not. The mean value over all births is 0.072, which implies an infant mortality rate of 72 deaths per 1,000 births.

To identify survey village locations most directly exposed to the effects of Dodd-Frank, we relied on the IPIS maps described previously. These maps give the geo-coordinates of artisanal mining sites during 2009-10, before Dodd-Frank was passed. We assume the legislation could have affected births that meet three conditions. First, the mother must live in a village within the spatial “policy zone” most explicitly targeted by the conflict-mineral policies.20 Second, the birth village must be within 20 kilometers of at least one 3T mine that was in operation prior to Dodd-Frank.21 Third, the birth must have occurred after Dodd-Frank was passed in July 2010. 22

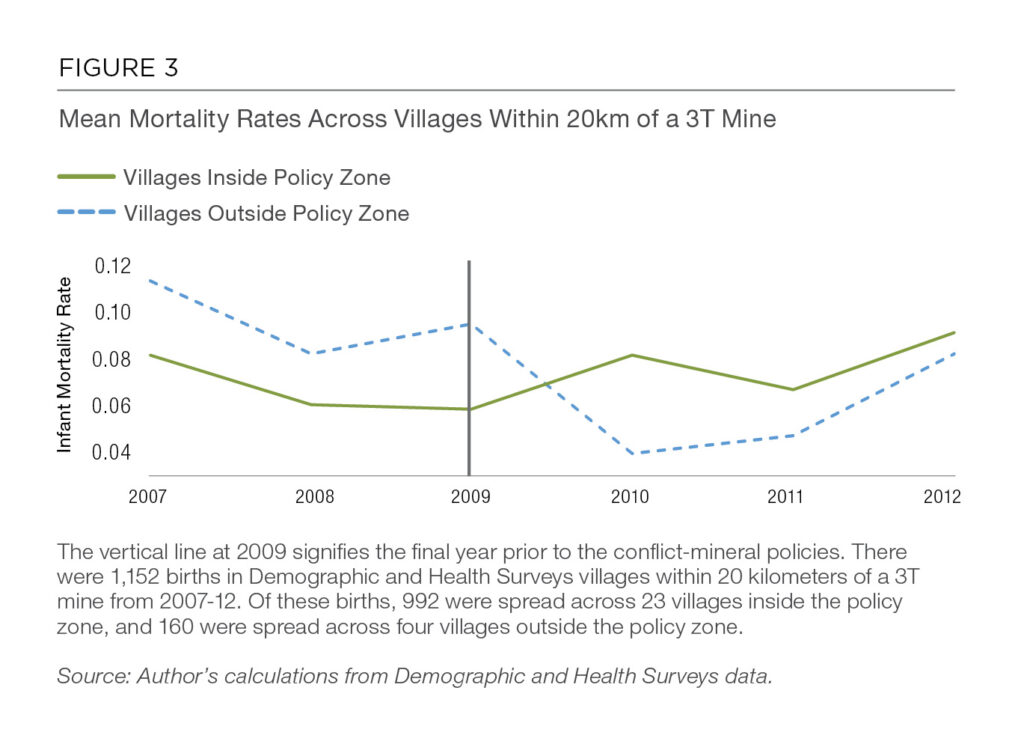

Figure 3 compares trends in mortality rates for villages within 20 kilometers of at least one 3T mining site, with the solid line representing the mortality rate in the villages likely to have been affected by Dodd-Frank. The dashed line represents the mortality rate in counterfactual villages within 20 kilometers of at least one 3T mine but outside the zone targeted by the mining policies. Comparing the two lines, the mean mortality rates in both village groups were following a similar trend through 2009, the final year before Dodd-Frank. Prior to 2010, mean levels of mortality were higher in the counterfactual villages, but in 2010, the situation reversed. This figure provides a visual indication that Dodd-Frank and the mining ban caused increases in mortality for targeted villages relative to other villages near mines not targeted by the policies.

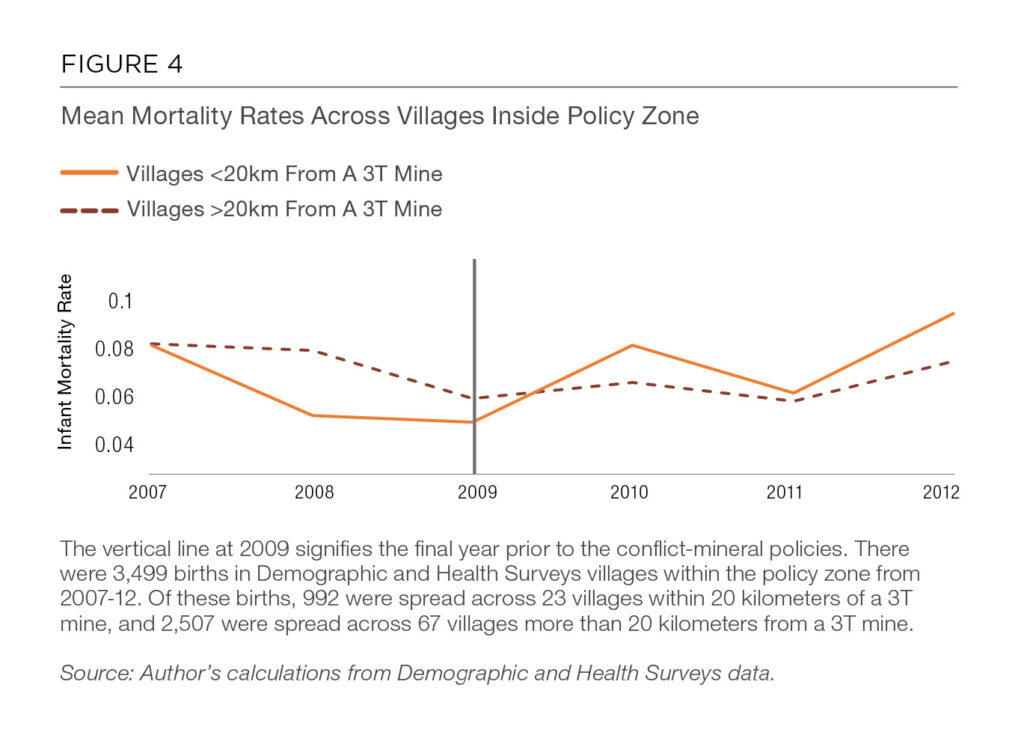

Figure 4 compares trends in mortality rates for two sets of villages within the policy zone: those more than 20 kilometers from a 3T mine and those less than 20 kilometers from such a mine. These villages should theoretically be subject to the same regional trends in mortality but differentially impacted by the conflict-mineral policies. Comparing the two lines, the mean mortality rates in both village groups were following roughly similar trends until 2009. Mean levels of infant mortality were higher in villages farther from 3T mines, which is consistent with the idea that infant mortality rates benefitted from being near an active mine. Beginning in 2010, the situation reversed such that mortality rates became higher in the villages close to 3T mines. This figure provides visual evidence that conflict-mineral policies increased infant mortality in villages close to 3T mining sites.

In our research, we controlled for factors other than the conflict-mineral policies that could have explained the patterns in infant mortality rates. These included factors that vary across infants, mothers, and villages—month and season of birth, birth order, household size, years of education, marital status, and precipitation levels, among other factors. In addition, we tested effects of the legislation by focusing on within-family comparisons of birth outcomes from the same mother.

The combined evidence suggests that Dodd-Frank increased the probability of infant deaths from 2010 to 2013 for children who live part of or all of their first year in villages targeted by the legislation. The most conservative estimate is that the legislation increased infant mortality from a baseline average of 60 deaths per 1,000 births to 146 deaths per 1,000 births over this period—a 143 percent increase. By contrast, we found no evidence that Dodd-Frank affected infant mortality in villages near gold mines, which were de facto exempt from the legislation-induced boycott as explained previously.

How exactly did Dodd-Frank increase infant mortality in villages near 3T mines? One possible explanation is that the legislation reduced families’ income levels and therefore limited their ability to access important health care goods, such as disease-preventing bednets. Demographic Health Survey data show that only 19 percent of mothers in the eastern DRC slept under bednets in 2007 compared to 58 percent in 2013. This growth is consistent with the general increase in bednet use across sub-Saharan Africa during the same time frame due to better availability, lower prices, and concerted information campaigns.23 We estimate that bednet use was about 20 percentage points lower in policy-targeted villages relative to what it would have been without the Dodd-Frank-induced boycott. Given the estimated price sensitivity of bednet usage in Africa, it is plausible that negative shocks to family income induced by the boycott drove decreases in health care consumption.24 Decreases in health care consumption could have also been driven by reductions in access to or higher costs of health care in the affected villages—both of which are plausible outcomes as the transportation of goods and services into affected villages declined along with their economic importance following the mineral boycott.

Effects on Violence

Dodd-Frank’s effect on infant mortality is one matter, but its impact on defunding militias and reducing violent conflict was the law’s primary aim. To study whether the policy successfully reduced conflict, coauthor Bryan Vadheim and I used the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset to assess the prevalence of looting, battles, and violence against civilians in the region after the legislation went into effect.25 The dataset provides information on internal conflict disaggregated by date, location, and by actor or actors for several unstable African countries, including the DRC.

The dataset spans 2004-12 and aggregates conflict events by month for each of the 70 territories of the eastern DRC.26 An event is classified as looting if an armed militia group’s actions are described by one of the following words: loot, pillage, plunder, rob, steal, ransack, sack, or seize. Battles occur between militia groups, including the Congolese army. Acts of violence against civilians are perpetrated by militias against civilians. Because it is plausible that positive shocks to agricultural wages—from plentiful harvests, for instance—can increase the incentives for armed groups to loot, we also used rainfall measures to determine when and where rains could have positively affected agriculture wages.

Our analysis revealed that Dodd-Frank and the related mining policies that followed triggered an increase in looting within the targeted territories, near mines, and even in surrounding areas driven by agriculture rather than mining. We also found evidence that the mining policies triggered battles in gold-dominated territories, but not in other territories.

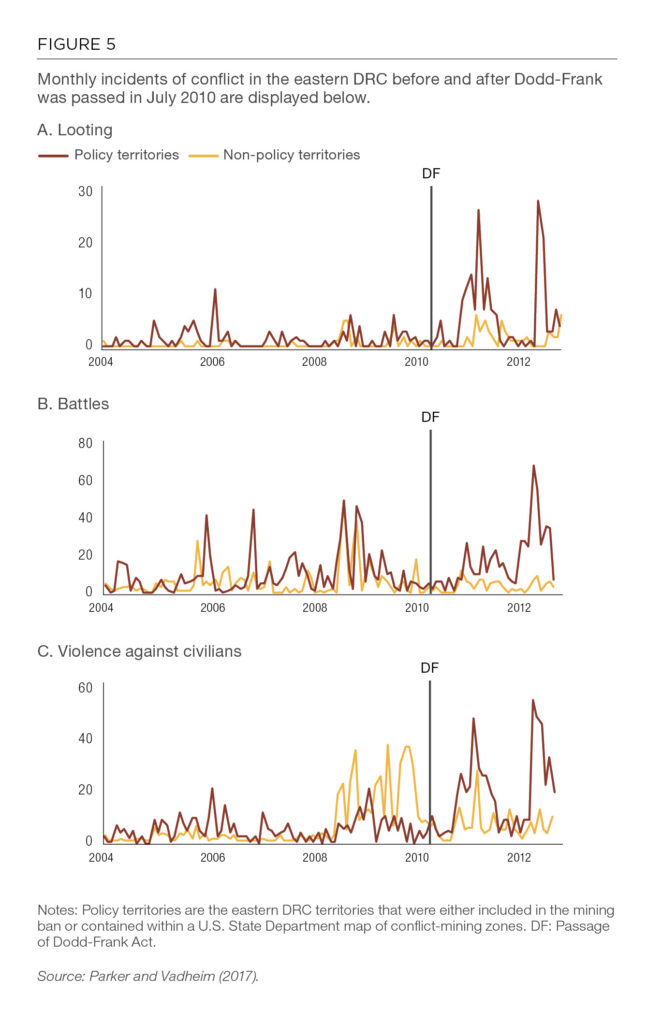

At the end of 2010, months after the passage of Dodd-Frank, looting events in the 27 territories targeted by the mining policies became much more common and remained that way through much of 2011 and 2012. There was not a commensurate rise in looting in the 43 non-policy-targeted territories, despite similar pre-Dodd-Frank trends across the two areas. The data also reveal that after Dodd-Frank passed, the number of battles occurring in policy territories increased relative to battles in non-policy territories. The incidence of violence against civilians also increased in the policy regions after the legislation, but there was no commensurate rise in the non-policy regions. Plotting the conflict events, as seen in Figure 5, provides detailed perspective on the timing of conflicts in policy and non-policy territories from 2004-12.

The evidence suggests that Dodd-Frank increased the probability of looting in the policy territories from an average likelihood of 3.0 percent to 5.3 percent. This implies that the probability of looting in policy territories increased by 176 percent after Dodd-Frank.

Our more detailed results also indicate that the probability that a policy-targeted territory would have an inter-militia battle increased with the number of gold mines in a territory after the passage of Dodd-Frank until 2012. This makes intuitive sense: Dodd-Frank would be expected to encourage battles over gold, because the policy raised its value relative to 3T minerals. Prior to Dodd-Frank, a policy territory with the mean number of gold mines—about 16 mines—had a 12.6-percent chance that a battle would occur within its borders. After the legislation, the probability of a battle happening in such a territory increased to 17.3 percent.

Another finding is that lagged rainfall anomalies positively correlated to the probability of looting. These results also make logical sense: Militias will look to steal agricultural surpluses, which increase with better rainfall conditions. We found evidence that looting increased in the aftermath of favorable rains that had presumably led to bumper harvests.

These findings are consistent with the deterioration of a “stationary bandit” equilibrium—a concept initially put forth by economist Mancur Olson in 1993. In the context of the eastern DRC, the idea is that militia groups who seek to stay in mining areas for years will not use violence to incapacitate its local mining workforce. On the contrary, such groups might invest in security and other provisions to avoid uprisings and work to keep mining areas safe and productive. This interpretation is consistent with the documented examples of some militias charging fees to enter mining sites and, in return, offering a degree of protection—even if only from themselves—as a mafia group would do.

According to this interpretation, armed groups that were stationed at 3T mines when Dodd-Frank passed had incentives to change their tactics. Rather than staying in mining areas that were on the wane, they found it more profitable to switch efforts toward looting civilians and fighting rival armed groups for the right to station at gold mining sites. At the same time, some armed groups that were formerly stationed at gold mines would have incentives to switch to looting civilians rather than engaging in battles with more powerful rival armed groups. Dodd-Frank, therefore, may have converted stationary bandits into more dangerous “roving bandits,” as Olson described them.27 He noted that the anarchy and plunder of roving bandits destroy “the incentive to invest and produce, leaving little for either the population or the bandits.”28

Our study examines conflict data up to 2012, but a recently published empirical study by researchers Nik Stoop, Marijke Verpoorten, and Peter van der Windt extends the analysis through 2015, using comprehensive and updated mining data. In their words:

Exploring the longer-term impacts of Dodd-Frank is important, as one could argue that the short-term negative effects of the policy may be offset by longer term gains. For instance, while the policy could indeed cause a disruption and greater violence in the short run, in the longer run, the purchase of weapons may be compromised if revenues of armed groups decline because of the de facto ban, potentially leading to a decrease in violent conflict. In addition, over time, US companies could restructure their global supply chain, organizing so-called closed pipelines, or a black market in ‘conflict minerals’ could develop; both of which could nullify the de facto ban, and its associated (un)intended consequences. If the negative effects of the policy persist over a five-year period, however, any long-term gains would have to be very large to offset the costs.29

Unfortunately, their analysis does not reveal much improvement in the situation since 2012. The authors summarize their study by noting that “our results echo the findings of Parker and Vadheim, and confirm that Section 1502 does not do what it intends to do.”30 In the longer term, battle incidents in gold mining areas remain high, suggesting that rebels continue to fight over gold sites. Moreover, the researchers detect a significant increase in riots, a sign of social upheaval. They did find one piece of good news: “an indication that looting of civilians (slightly) decreased in 3T mining areas.”31

Conclusion

The top-down decision by the U.S. Congress to regulate “conflict minerals” did not reduce human suffering in the eastern DRC. Instead of reducing violence, the evidence indicates that, at least in the short term, the mining policies increased violence against civilians. The policies also appear to have increased infant mortality, demonstrating how interventions that intend to enhance human rights can unintentionally harm the vulnerable populations they seek to protect.

The findings summarized here are consistent with other, more qualitative research that also points to adverse policy effects. These results add quantitative support for detailed investigations that have suggested the conflict-minerals policies impaired economic conditions for marginalized populations who had relied on informal mining.32 Among other shortcomings, the legislation was poorly targeted, it did not anticipate the displacement of conflict to gold mining sites, and the drafters assembled insufficient input from the local population before executing the policy.

Advocates of Dodd-Frank Section 1502 could argue the legislation needs more time to work, and it is possible that long-run benefits for infant health and household welfare will eventually emerge if the legislation can reduce conflict and enable mining to resume. Even if it does, it is worth asking if the short-run human costs that have already been suffered were justified.

Today, the future of Section 1502 is uncertain. In 2017, the Trump administration drafted an executive order that called for suspending Section 1502 and replacing it with a “more effective” policy, which raises questions about why the measure was flawed and what kind of policy might work better.

A better-targeted certification program could have caused less collateral damage, especially if it were offset with commensurate health care and income aid to help families near mining villages.33 But why was the targeting so blunt? A 2014 open letter by a group of local and international experts provides ideas. The letter argues that a key flaw of the conflict-minerals legislation was that it demanded companies prove the origin of minerals well before monitoring systems able to provide such proof were in place.34 This lack of monitoring capacity resulted in the de facto boycott. A better approach, perhaps, would have been to give companies waivers for compliance until monitoring systems were in place, or to create a default rule in which minerals were considered conflict free unless proven otherwise.

At a more fundamental level, we should ask what might have happened if the money spent on Section 1502 compliance and lobbying—reportedly billions of U.S. dollars—was instead spent on alternative forms of foreign aid aimed at bolstering human rights in the eastern DRC. Could an alternative policy—one that leveraged a budget of billions of dollars—have been effective at reducing militia control while at the same time benefiting local populations?

There is a general strategy that economists might endorse: Use foreign aid to raise the opportunity cost of engaging in conflict. If foreign policy can successfully give young men in the DRC better alternatives than militia participation, then conflict might be reduced through voluntary exit out of militias or out of risky mining areas. Foreign interventions that create better opportunities in rural areas, or that reward “conflict-free minerals” rather than penalizing conflict minerals, might achieve this. At the very least, such interventions might avoid simply shifting conflict to other places or causing a boycott of a region where jobs, income, and health care are already scarce.

Download the full report, including endnotes and references.