Will the lion’s roar grow faint in Africa’s wildlands? That is a question increasingly being asked by scientists, managers, and conservation practitioners as the king of the jungle faces growing pressure from habitat loss, killings in response to livestock predation, and the illegal bushmeat trade. To help keep the king on the throne, a coalition of entrepreneurs, donors, and hunters has embarked on an ambitious project: restore two prides of lions to Mozambique’s Marromeu Ecosystem. If successful, they will increase the range of the African lion by more than 2.4 million acres—an area larger than Yellowstone National Park—improving the health of not only the species but of a landscape long battered by civil war.

The project has its roots in the work of South African professional hunter and entrepreneur Mark Haldane. In 1992, Mozambique signed an internal peace agreement, ending 25 years of nearly uninterrupted and violent conflict that left more than 1 million people dead and decimated the country’s wildlife populations. Haldane stepped into this fragile environment in 1994, assuming responsibility for Coutada 11, a government-designated hunting area in the remote Zambezi River Delta. There he launched his business, Zambezi Delta Safaris.

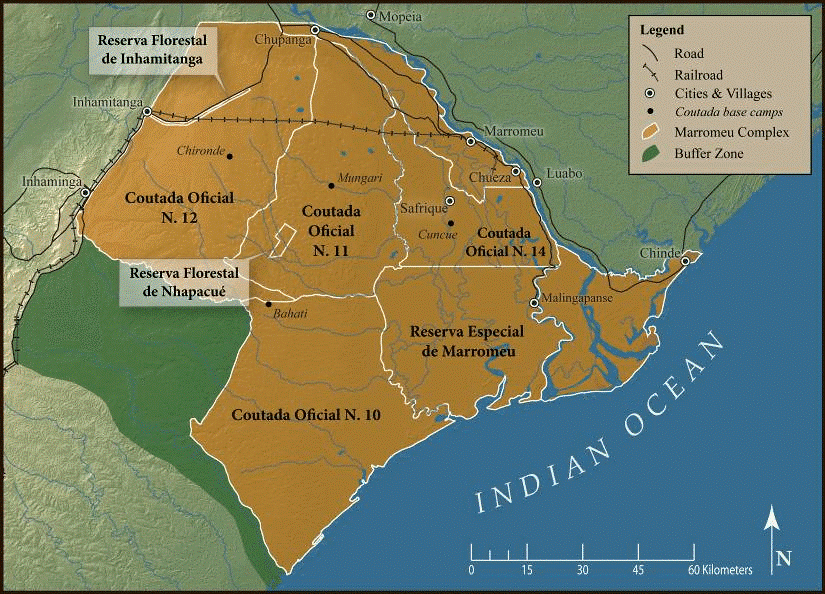

Like all entrepreneurs, Haldane was taking a risk when he first set up camp in Coutada 11. The area occupies a core position in what is known as the Marromeu Ecosystem. Covering the southern half of the Zambezi River Delta, the Marromeu includes a total of four hunting areas, the Marromeu Buffalo Reserve, two forest reserves, as well as agricultural and communal lands. In 2003, the area was designated as Mozambique’s first and only “Wetland of International Importance” under the international Convention on Wetlands. Still, after years of war, the woodlands, marshes, and prairies of the Coutada were largely devoid of game, the herds having been overhunted to feed hungry armies. Only 44 Sable antelope remained, and the cape buffalo herd stood at just 1,200 head, a difficult base on which to build a sustainable hunting business.

But Haldane is not a man who is easily discouraged. Over the quarter century that followed, he worked with local communities and conservation professionals to nurse the area back to a level of ecological health necessary for his investment to convert. This was no easy feat considering the daunting scale and terrain of the Coutada’s 2.5 million acres. Still, Haldane persisted, using research to guide game management and establishing a counter-poaching program in partnership with local communities to limit wildlife crime.

As his business slowly grew, Haldane was able to reinvest more of his profits, along with client donations of roughly $80,000 per year, into conservation programs. That included an anti-poaching unit made up of former poachers recruited from local villages. It was the first time most of them had ever collected a salary. The income provided critical and often scarce cash resources for their families.

Haldane also built trust and rapport with his employees’ communities, beginning a program that distributed meat from animals shot by trophy-hunting clients to villagers, reducing the need for anyone to poach for food. Haldane even went a step further and worked with the government to establish a quota of more common animals that would be harvested for the sole purpose of feeding the communities. A school was built for local children with the help of a generous donation from a hunting client. A mobile corn mill was also established. There was an understanding that if poaching continued, all of this might be lost. Poachers went to Haldane to turn in their traps and snares. The opportunity cost of poaching became too great to continue the illicit practice.

In time, Zambezi Delta Safaris would employ approximately 150 local people, and Haldane’s unyielding commitment would deliver one of the greatest conservation success stories in modern Africa. Coutada 11’s cape buffalo herd grew to 21,000 animals, large enough to serve as a source population for reintroduction efforts elsewhere in Mozambique. The Sable antelope population grew to 3,000, roughly the same number as existed before the war. The country’s elephant population has similarly returned to pre-war levels, according to investigations by World Wildlife Fund researchers. Populations of crocodile, reedbuck, hartebeest, warthog, Livingston’s suni, zebra, and hippos have also been on the rise.

“Through the success of our anti-poaching program,” says Haldane, “right now we are at the point of capacity with regard to most game species. Bringing back the large predators is the next step. The first thing that breaks in a natural environment such as this is the circle of life. We have one link missing, and by bringing the lions back we’ll complete the circle.”

The vision of returning lions to Coutada 11 and the wider Marromeu Ecosystem couldn’t be more timely. Lion populations are difficult to measure precisely, but in 1950 the best estimate showed that 200,000 lions roamed the African continent. Today, between 20,000 and 30,000 wild African lions remain, occupying roughly 20 percent of their historic range, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s African Lion Working Group. The Regional Lion Conservation Strategy for Eastern and Southern Africa, a blueprint adopted by the working group and 10 other international conservation organizations, estimates that between 450 and 950 lions still roam Mozambique, with the bulk of them concentrated in wildlands just north of Coutada 11 and the larger Marromeu Ecosystem.

How exactly does one go about returning lions to a remote wildland where they have not been seen in decades? With a great deal of help. For that help, Haldane turned to the Cabela Family Foundation and the Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance for unique support and the expertise they could provide. “It’s a bold, big project,” says Dan Cabela of his family foundation. “Lions used to exist here and they should exist here now.”

To source the lions, the partnership looked to South Africa, where long-established private property rights in wildlife have made the country home to one of the largest lion populations in the world. Wildlife veterinarian Mike Toft was enlisted and given the challenging job of finding 24 lions with diverse genetics for the reintroduction effort. The two-dozen threshold was purposely chosen because a minimum of 10 lions is required for a pride to be considered viable. Reintroducing 24 lions in the Marromeu would establish two prides in the area, creating a degree of redundancy that would improve the chances of long-term success.

Once the lions were identified, they were sedated, loaded onto aircraft, and flown to Mozambique. There they were placed in bomas, specially built enclosures that would allow them to acclimate to their new home in the Marromeu. The airlift made the aptly named 24 Lions Project the largest international translocation of lions in history.

After months of work, the first lions were released into the wild on August 5, 2018, and the vision of a free-ranging lion population in the Marromeu Ecosystem became a reality.

“This is the front line of conservation, and this is a bold move for the African lion,” says Ivan Carter, founder of the Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance and a member of the International Wildlife Conservation Council established by U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke.

In the weeks since the release, the lions have by all accounts acclimated well to their new surroundings, hunting the area’s abundant warthog and reedbuck. Sadly, one lion died soon after leaving the boma, but it was soon replaced by a lone, nomadic male from outside of the Marromeu who had taken a liking to one of the reintroduced females, restoring the total number of lions to 24.

Though Mozambique is open to lion hunting and the reintroduction was initiated and backed by hunters, none of the reintroduced lions will be hunted. The hope is that they will serve as a seed through which the area’s total lion population will eventually increase to 500. One of the females is already showing signs of pregnancy.

To help lions fully recover in the Marromeu, the project’s backers have outfitted the lions with radio collars and made them the subject of a long-term scientific study. “With the arrival of these lions, it presents a really unique opportunity to study the effect of predation on the ecosystem,” says zoologist Byron Du Preez, who is leading the research effort, along with Samuel Bila and Carlos Manuel Bento. “The exciting part now starts, because we get to see these lions go from zero to recolonizing a significant area of their former range.”

Whether the reintroduction of lions into the Marromeu is a durable success that can be replicated elsewhere depends in part on U.S. policy. While the Fish and Wildlife Service agrees with findings that lions in southern Africa are not in danger and that populations are in fact increasing, that did not stop the agency from listing the species under the Endangered Species Act in 2015. The listing empowers the agency to regulate imports of legally acquired lion hunting trophies, including limiting those imports based on arbitrary standards. This can be enough to discourage Americans from hunting lions in Africa and, in turn, hamper the growth of businesses like Zambezi Delta Safaris that are producing positive conservation results on the continent.

Researchers from the University of Pretoria and the conservation organization Panthera found that lion hunting generates 5 to 17 percent of gross hunting revenues in certain African countries, with Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia the nations most reliant on lion hunting. The preclusion of lion hunting in these countries risks the economic viability of hunting operations and potentially puts 14,712,160 acres of wildlands, currently managed as hunting blocks, at risk of development.

When Congress passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973 by a near-unanimous vote, it intended the law to support efforts like those being undertaken by the partners in the 24 Lions Project—not to risk millions of acres of habitat through the imposition of regulations that undermine the holistic conservation programs of America’s international partners. Both Congress and the Trump administration are weighing potential reforms to the Endangered Species Act. It would be wise to look at what has been accomplished in Mozambique and how partnerships between businesses, the national government, and dedicated conservationists like those who permeate the hunting community have leveraged the incentives and revenue produced by hunting programs to take a war-battered landscape like the Marromeu Ecosystem and restore it into a wildland paradise where lions once again are king.

In the meantime, the partners in the Marromeu lion reintroduction are relishing the return of lions to the ecosystem and the reignition of the ancient dynamic between predator and prey. They are also looking ahead to building on what promises to be one of Africa’s great conservation success stories, with whispers about the possibility of someday returning cheetah to the area as well. Whether that could ever come to pass depends in part on whether hunting remains a viable industry in Mozambique—something that remains very much in question so long as current U.S. policies remain in place.