Mention the word “Serengeti” to a room full of informed and enthusiastic lovers of nature and, to a person, there is no question what you are referencing. The same kind of instant place recognition exists when one says “Yellowstone.”

Now meld those two geographical icons together into this: American Serengeti. Although the allusion may initially elicit head scratching for some, it is this conjunction that represents one of the most exciting frontiers for 21st century landscape-level conservation.

Yes, there’s a parallel to be drawn between the heralded mass movement of millions of large mammals across the famous plain in eastern Africa and to the ironically lesser-known terrestrial marvel happening right in the middle of the American West.

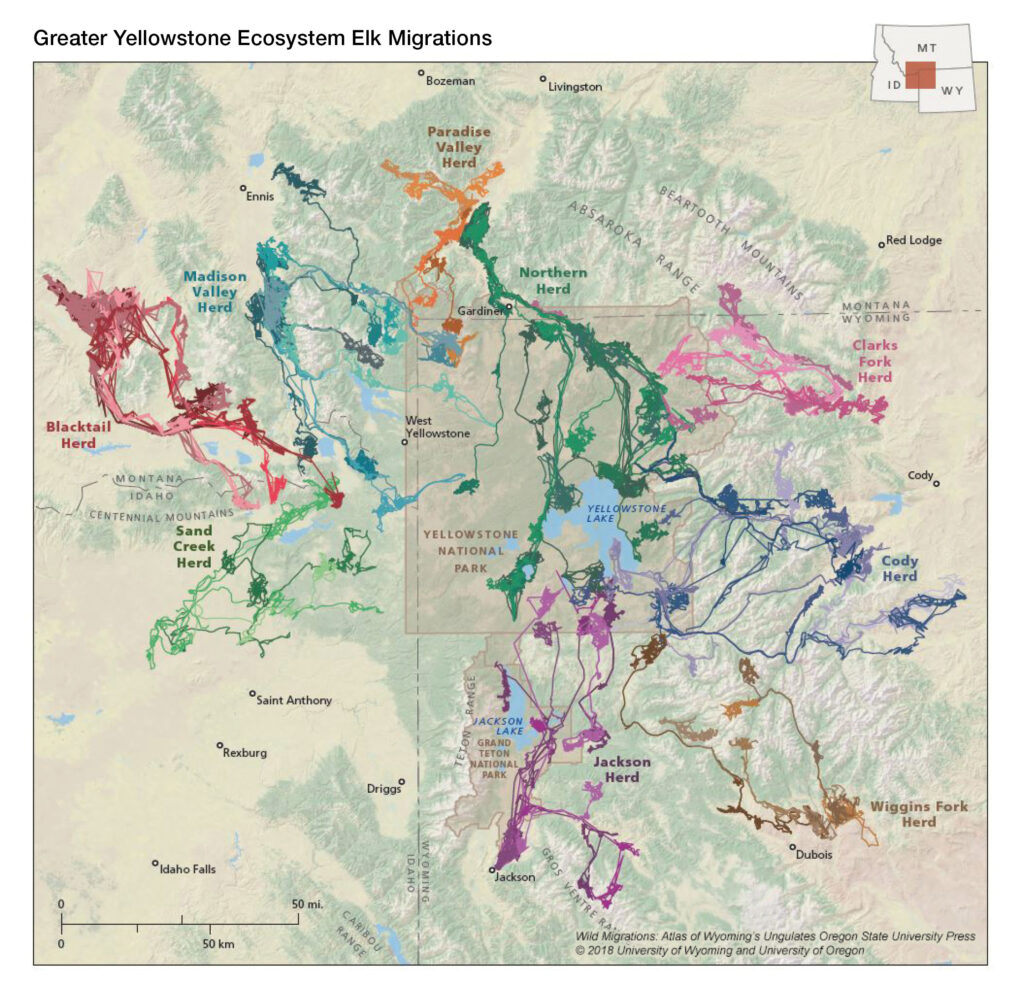

Yellowstone, the world’s first national park, represents a central hub not only for tourists. It’s also a nexus to some of the greatest Serengeti-like wildlife migrations still occurring on the North American continent. Encompassing the park and the mosaic of public wildlands and private property surrounding it, the larger Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is home today to the longest migrations for elk, mule deer, and pronghorn known to exist.

Although the phenomenon has been happening for millennia—active use of the pathways stretch back 8,000 years, predating construction of the Egyptian pyramids—these unparalleled treks of charismatic megafauna in Greater Yellowstone have, in fact, only recently been “discovered” and mapped. Thanks to GPS technology and sophisticated tracking devices, the journeys are only now being understood.

“All along, these migrations were right under our noses,” says Matthew Kauffman, “and though generally we knew wildlife moved seasonally between high elevations and lower terrain, we didn’t understand fully the whys and wheres.” Kauffman is a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and a leader of the Wyoming Migration Initiative, an internationally recognized, multi-agency research outfit pioneering the study of migrations.

Kauffman likens the giant leap in knowledge of these migrations to scientists having their eyes opened upon the invention of electron microscopes to a mind-blowing, previously unknown world of super-minute life forms, including germs, bacteria, and single-cell organisms. It existed nearly invisibly just beyond the grasps of human comprehension.

“I’ve come to think of these migrations as being kind of a pulmonary system of Greater Yellowstone. During spring and summer, imagine the landscape ‘breathing in’ elk like lungs into the central high country of Yellowstone and nearby wilderness areas, and then in fall and winter the herds move outward, like a deep exhalation, to lower land, to get out of deep snows in order to survive.”

Now, on a macro-scale at the opposite end of the spectrum, satellite technology has illuminated the routes of hundreds of thousands of wild hooved animals, wonders of nature that command as much awe as the movements of neotropical songbirds flying thousands of miles twice a year between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, the remarkable life histories of sea turtles, or the journeys of spawning salmon.

That’s the inspiring, tantalizing part of “the American Serengeti.” Yet accompanying the emerging revelations is a daunting reality: Without creative actions to secure landscape protection in the next few decades, these ancient animal movements and the integrity of the corridors they depend on could be lost forever.

The Marvel of Hooved Migrants

Often wending as tributaries and sometimes forming larger confluences of animal masses, Greater Yellowstone’s ungulate movements are every bit like wild free-flowing streams unencumbered by dams. For the public, it means that one doesn’t have to travel around the globe to witness epic crossings; they are right here, still hanging on by dint of miracle, in America’s backyard.

Kaufmann’s colleague Arthur Middleton, a leading elk migration researcher who is affiliated with both the University of California-Berkeley and University of Wyoming, eloquently described these seasonal treks when I spoke to him in 2016 for National Geographic: “I’ve come to think of these migrations as being a kind of pulmonary system of Greater Yellowstone. During spring and summer, imagine the landscape ‘breathing in’ elk like lungs into the central high country of Yellowstone and nearby wilderness areas, and then in fall and winter the herds move outward, like a deep exhalation, to lower land, to get out of deep snows in order to survive.”

Like spokes leading to the center of a wheel, at least a dozen different elk herds, comprising tens of thousands of animals, follow the “green wave” of grass in spring onto the Yellowstone Plateau, a high mountainous area in the national park where cow elk raise their calves and put on body weight before leaving when the snow begins to fly. The good nutrition they find along the way is what drives individual animal and herd health, including fecundity. Elk physiology is perfectly timed to be at the right place at the right time, when available food is available to propel the animals forward.

All of Greater Yellowstone’s major wild hooved animals—elk, deer, pronghorn, moose, bison, bighorn sheep, and mountain goats—move as part of their evolutionarily ingrained behavior, part of learning passed down in herds from mothers to young over hundreds of generations.

Just south of Yellowstone, a pronghorn population spends its summers in Grand Teton National Park and the valley floor of Jackson Hole, Wyoming. In the fall, it departs on a pilgrimage of more than 150 miles through national forests, public rangelands, and cattle ranches southward to the flanks of the Wind River Mountains and Wyoming’s Red Desert.

Yet certainly the most impressive commuting prize—at least of what’s been uncovered so far— goes to a mule deer. One famous muley doe, research animal No. 255, was shown to travel nearly 250 miles between the Red Desert on the southern tier of Greater Yellowstone and Island Park, Idaho—and then, astoundingly, back again.

Distance wise, that’s like a deer summering in New York City and wintering in Washington, D.C. More extraordinary is that just one way of Deer 255’s trek involved the following: crossing two different national forests, a national park, and the Continental Divide; meandering to and fro across busy highways, through rivers, and over fences; avoiding predators such as wolves, bears, cougars, domestic dogs, and human hunters; and circumnavigating Jackson Hole, the north side of the Tetons, other mountains, and various towns and farmland. She did all of this, then turned around and did it again in the opposite direction.

Scientists are now in the early stages of understanding the ecological function of these ungulate migrations. The groundbreaking research commenced by the Wyoming Migration Initiative and the Wyoming Game and Fish Department is being expanded to neighboring Montana and Idaho.

All of Greater Yellowstone’s major wild hooved animals—elk, deer, pronghorn, moose, bison, bighorn sheep, and mountain goats—move as part of their evolutionarily ingrained behavior, part of learning passed down in herds from mothers to young over hundreds of generations. Why it still happens in Greater Yellowstone is simple. Epic wildlife migrations used to exist across most of America, but various kinds of habitat fragmentation have created impassable barriers, causing some of the migrations to die out. The Yellowstone region has corridors of open space through which animals can still pass.

To return to Middleton’s metaphor: “Just like a pulmonary or circulatory system in the human body, if you have a blocked or clogged artery or obstructed breathing passage, you’re in trouble,” he says. “If these migration routes are going to persist, then protecting the pathways where they happen is essential.”

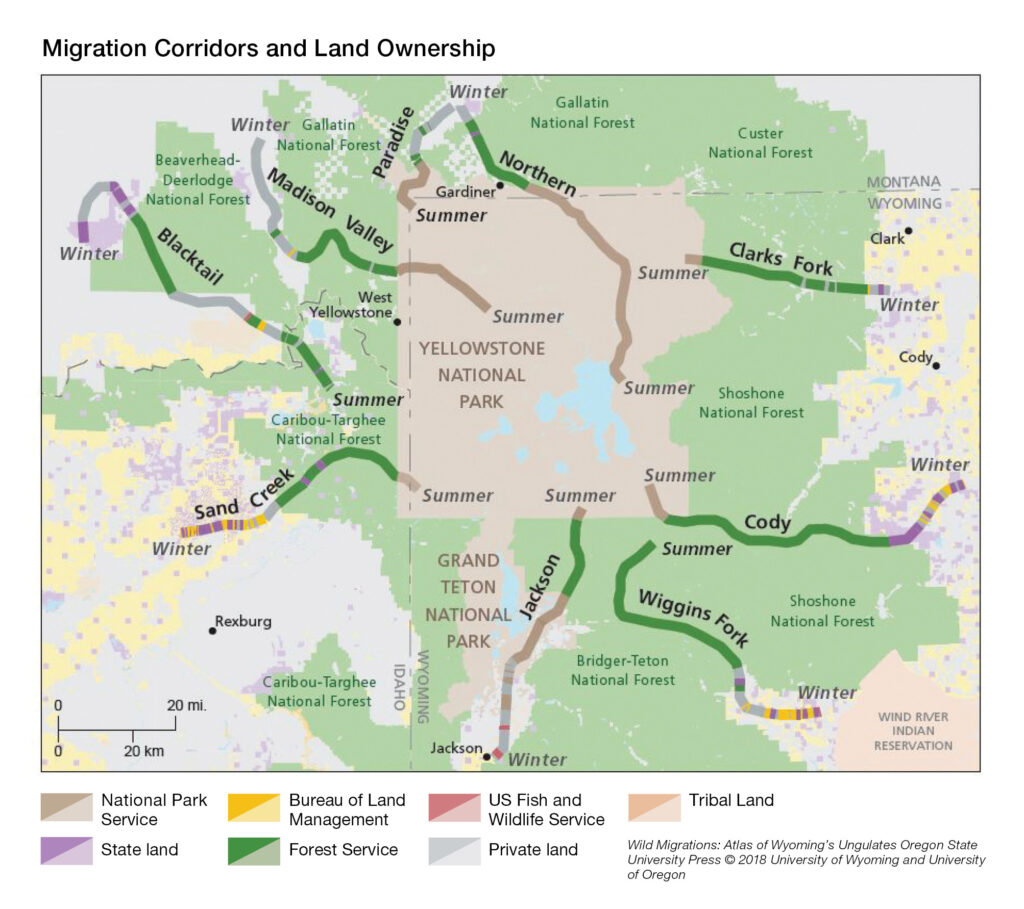

The Greater Yellowstone region encompasses more than 22.5 million acres across three different states and 20 counties. Most of it consists of federal public lands managed by the National Park Service, Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Fish and Wildlife Service, plus some state-owned tracts in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho.

“It’s stretching our thinking about how to best manage wildlife cooperatively in a way that transcends boundaries and yet respects them,” says Yellowstone National Park Superintendent Cam Sholly. “You can’t protect what you don’t know exists, so documenting what happens in a spatial and temporal sense is really important.” Sholly is the new chairman of the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee. The GYCC, as it’s known, comprises senior land managers from all relevant federal and state agencies. It has made corridor protection a priority, and it has support from both the U.S. Interior and Agriculture Departments.

Migrations are more than merely seasonal events involving animal travel. They have a symbiotic relationship with ecological well-being and in some ways represent the bottom tip of an inverted pyramid. When animals move across the landscape, it is about more than them simply traveling between two seasonal home ranges. They are like the sparks that flow through circuitry—transporters of energy. They indirectly convert light from the sun, which has triggered photosynthesis in plants that grow and are eaten, into calories that not only sustain the animal but put on body mass.

As they travel, their bodies support the survival of an array of other species, from grizzly bears to wolves and mountain lions. In death, their carcasses sustain an array of scavengers, from coyotes and foxes to eagles, ravens, and rodents to beetles that aid in decomposition and foster healthy soils. The grasslands of Greater Yellowstone evolved to be eaten by ungulates; healthy plants and soils absorb carbon and, in turn, nourish other life forms.

The Importance of Private Landowners

Were it simply a matter of developing a migration corridor strategy for public lands, the challenge would be much simpler. However, interspersed among public lands are roughly 5 million acres of private property, taking the form of towns and agricultural lands that experts say represent the most important pieces of the puzzle.

In many ways, the entire Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem depends directly on the goodwill of private landowners, and indeed, they are key in leveraging the functionality of wildlife corridors. Greater Yellowstone is the birthplace of three major river systems—the Snake-Columbia, Green-Colorado, and Missouri-Mississippi, with a dozen other rivers and hundreds of major creeks feeding into them.

Here, as in the rest of the arid West, river valleys were settled first because they had access to water. River corridors and the uplands flanking them are known as “riparian areas.” They’re the most productive and important habitat, especially in winter months, and represent vital areas of movement for wildlife.

Today, portions of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem are being inundated by rapid human population growth, rising numbers of outdoor recreationists, energy development, and increasing traffic on roads. Some ecologists say it’s a race against time to identify the routes and keep them open.

Consider two data points. In the far northern tier of Greater Yellowstone is one of the fastest growing micropolitan areas in the country: Bozeman, Montana. The current pace of growth would result in the city’s population doubling roughly every 17 years, meaning the area’s population could swell from nearly 110,000 today to 220,000 by 2037. At the southern tier of the ecosystem, development of oil and natural gas on public lands already is disrupting wildlife movements.

There’s certainly a compelling economic case to be made for the value of the corridors. Nature tourism in Greater Yellowstone, which still has its full complement of species that were present when Europeans came to the continent, is big business. Akin to the Serengeti, it brings money to the region. Between Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks alone, visitation supports more than 15,000 jobs and $1.4 billion in annual economic activity. Wildlife watching, which attracts tourists from around the globe, is a major driver. In addition, ungulate herds support a robust guiding and outfitting industry and are the backbone of local hunting traditions.

Not long ago, I spoke with Abby Nelson, a wildlife specialist with the Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks Department. She said that more than 80 percent of public wildlife coming off of public lands when the snow begins to fall spend all or part of the winter on private land, especially large cattle ranches. These migrations provide a fine lens for understanding why these private lands—and private property rights in general—matter so much, and why broader thinking about how conservation can succeed is necessary. As the latter half of the 20th century demonstrated, the old way of simply drawing a line around public lands and believing they are enough to sustain wide-ranging wildlife isn’t enough.

In fact, it’s something ranchers have known for generations because every winter they have hosted public wildlife on their lands. Today, as many ranchers operate with thin profit margins and younger generations increasingly buck ranching as a profession, thousands of acres of private land crucial to the health of migrations are at risk of being converted into scattershot sprawl that can be detrimental to migratory wildlife.

Fortunately, seldom in the storied history of Greater Yellowstone has there been a more united effort involving such a wide variety of groups and stakeholders as there is to conserve the region’s migration corridors. PERC has emerged as a leader because its raison d’etre as an organization is identifying ways that market-based solutions and economic incentives can be applied to advance better conservation outcomes.

When thousands of elk, for example, head to lower ground, they cross and seasonally inhabit private ranchlands where they compete with livestock for forage, knock down fences, and can transmit diseases to cattle. A major focus is developing a corridor conservation strategy that incorporates the local on-the-ground knowledge that rural landowners possess and understands and addresses their challenges of living with wildlife.

“It is important that private landowners be treated with respect as allies and that their involvement as long-time habitat stewards is recognized and rewarded,” says Brian Yablonski, executive director of PERC who previously worked closely with landowners when he served as chairman of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Lots of different groups, realizing time is of the essence, are making meaningful contributions. PERC is filling a niche no other conservation organization can—by working with both landowners and conservationists to explore how markets can create opportunities for conservation that regulations can’t.

“What many landowners want most is to have their voices heard and their property rights respected,” Yablonski says. “Making migration work for them is both an opportunity and a challenge. Vitally important is having management flexibility to use creative options and help make coexistence happen in a way that addresses both the needs of ranchers and wildlife. If these wildlife corridors are going to be saved, solutions need to flow from the ground up. As the father of wildlife ecology, Aldo Leopold, noted, the best kind of durable conservation begins with respecting those who live with it, and when you do that, everyone can benefit.”