DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

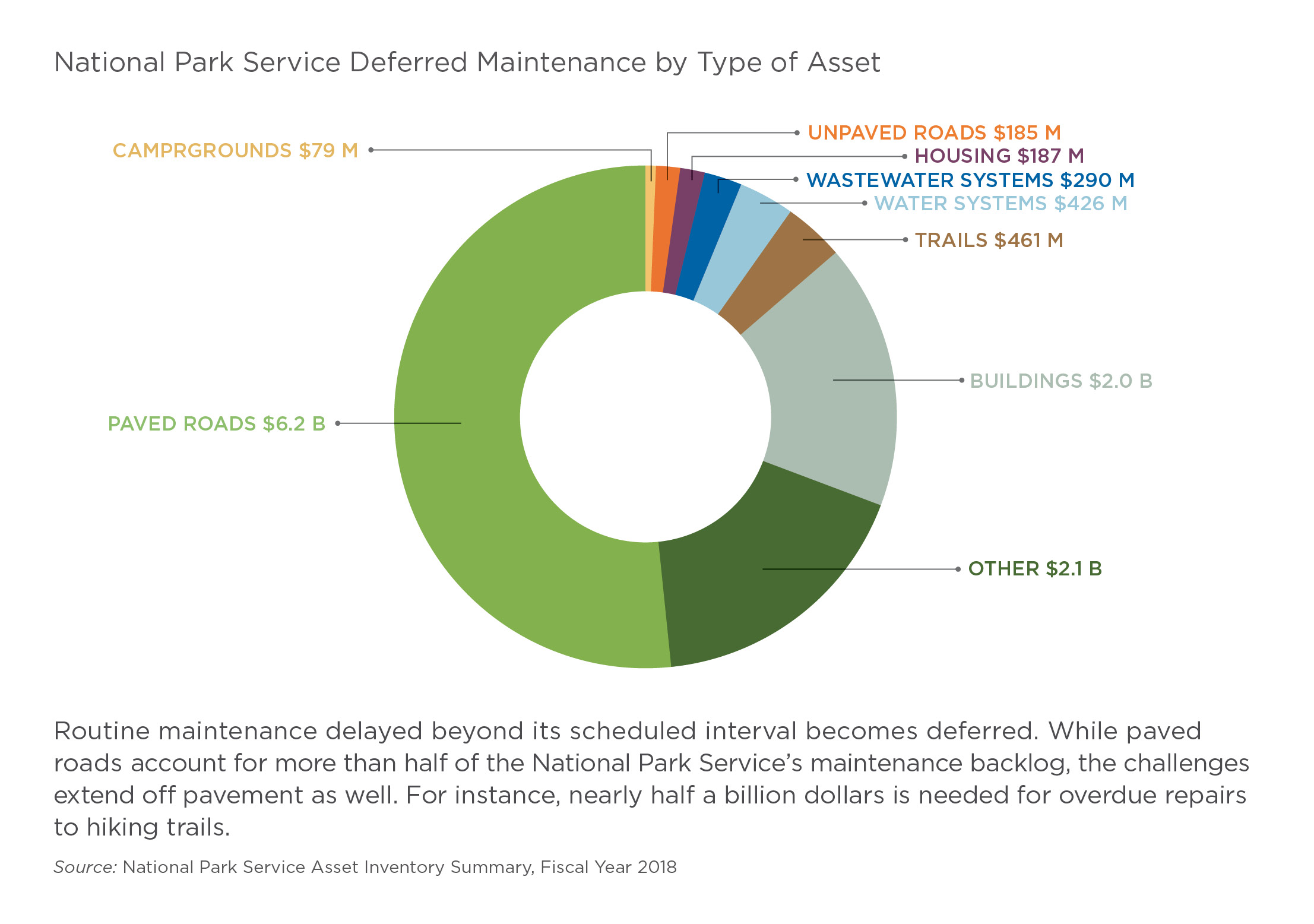

The immense backlog of overdue maintenance in national parks has received a great deal of attention in recent years. The unmet repairs, which include eroding trails, dilapidated visitor centers, failing wastewater systems, and many other needs, now total nearly $12 billion. The predicament has drawn the notice of legislators, who devoted significant funding—up to $9.5 billion over five years—to deferred maintenance across all public lands through the Great American Outdoors Act.

The deferred maintenance fund created by the act is a step in the right direction, but even if the entire backlog were addressed overnight, policymakers have yet to reckon with the underlying issue that spawned it: a lack of attention to routine maintenance. When park assets are not serviced on time as part of today’s cyclic maintenance, they become tomorrow’s deferred maintenance. And while the act commits meaningful funding for maintenance projects that are already overdue, it will not solve the fundamental problem of insufficient attention to routine maintenance that created the backlog in the first place.

- Eliminating all existing deferred maintenance would not address the lack of attention to and funding for routine maintenance that created the backlog in the first place.

- Revenues from visitor fees could do more to address routine maintenance, but internal agency policy often prevents fee receipts from being used for recurring expenses such as routine maintenance.

- Perverse incentives to let maintenance lapse increase the overall maintenance burden and cost parks, visitors, and taxpayers more in the end.

- Park superintendents have good information about their own maintenance needs and how to meet them, but they need the proper resources and adequate flexibility to address them.

National parks need dependable funding for routine maintenance so that they avoid ending up in another maintenance hole in the future. There are also opportunities to diminish maintenance requirements by contracting out certain services, making calculated judgments about park infrastructure that no longer justifies its costs, and adopting sound fiscal strategies for maintaining assets over the long run.

Recommendations:

- Prioritize the maintenance of existing parks over adding new units to the system.

- Improve flexibility in setting and spending recreation fees so that parks can harness the revenues they generate more effectively.

- Contract out services and activities where feasible and appropriate.

- Calculate whether certain infrastructure assets no longer justify maintenance costs and qualify for disposal.

- Implement strategies to maintain roads in a financially sustainable way.

The Underlying Maintenance Issue

The fundamental maintenance problem in national parks stems from putting off routine maintenance for lack of funding. Maintenance needs fall into two categories. Cyclic maintenance includes repairs or services that should be conducted at regular intervals or on recurring schedules. Deferred maintenance is maintenance that has been delayed beyond its scheduled interval. The most recent budget request from the National Park Service underscores the importance of keeping up with routine maintenance before it can become deferred:

When cyclic maintenance is not performed on schedule, assets begin to deteriorate. Deteriorated assets can face unexpected closures when systems fail, interrupting public access or use and it is often more expensive and time consuming to correct asset deterioration than to perform routine maintenance. Cyclic maintenance performed on schedule prevents asset deterioration, minimizes impacts to recreational access, and ensures a higher quality visitor experience.

Whether repainting and reinforcing a structure, resurfacing a road, lubricating machinery, inspecting and replacing parts, or completing other preventive tasks, cyclic maintenance can reduce repair costs, extend the life cycles of park assets, and ensure visitors’ experiences are not impacted by closures. When cyclic maintenance goes undone, the deferred maintenance challenge snowballs. This is especially true at older park units, which account for the majority of deferred maintenance. More recently, some newer park assets have been built without sustainable fiscal strategies to address routine maintenance over their life cycles, compounding the challenge.

Deferred maintenance begins as routine maintenance.

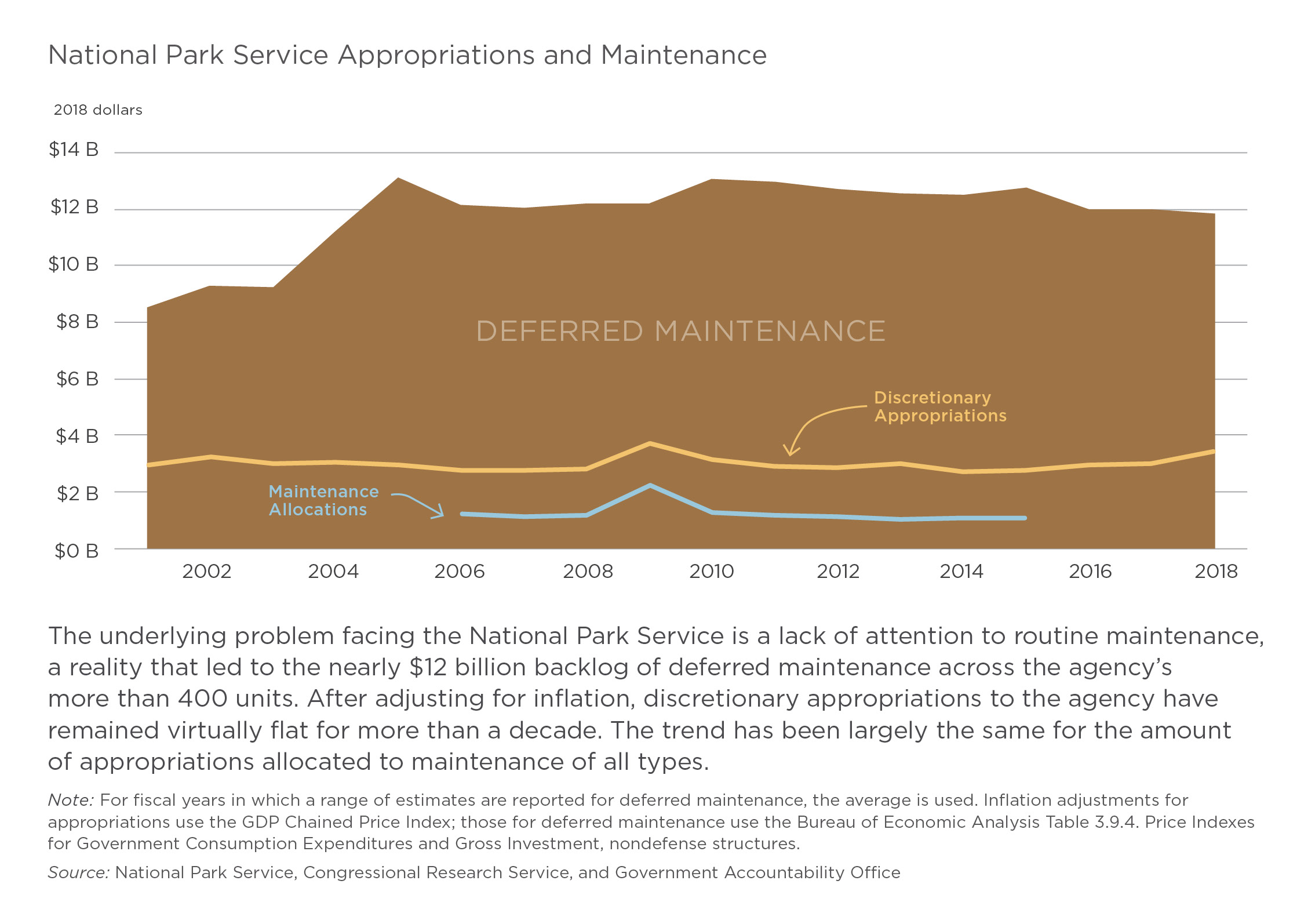

Eliminating all existing deferred maintenance would not address the lack of attention to and funding for routine maintenance that created the backlog in the first place. For years, funding for parks has not been sufficient to keep up with the maintenance needs of aging assets and infrastructure. The majority of park funding comes from appropriations, and the congressional appropriations process is inherently political—a reality that exacerbates the maintenance problem. “It’s fun and sexy to add a new unit to the Park Service,” Rep. Rob Bishop (R-Utah) has said in acknowledging this issue. “It’s not fun or sexy to talk about fixing a sewer system.” Much of the longstanding neglect of maintenance can be explained by politicians failing to prioritize activities like fixing wastewater systems.

It is possible that years of attention on the deferred maintenance challenge has changed the political calculus recently, helping stem the growth of the backlog, if not reduce it. As one example, the Great American Outdoors Act established the National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund, which will receive up to $1.9 billion annually over the next five years to help address deferred maintenance. But the underlying problem of insufficient funding for routine maintenance remains unaddressed. The fund will only be available to address one-off deferred maintenance projects, not recurring expenses associated with routine maintenance.

In a system of more than 420 park units with a diverse mix of missions and assets, determining the optimal amount to spend on maintenance is a complicated proposition likely best decided on a park-by-park basis. Nevertheless, examining the system-wide backlog provides a sense of the magnitude of the challenge. The National Park Service estimated in 2013 that it would need to spend nearly $700 million on deferred maintenance annually just to keep the backlog constant. While the agency does not systematically report a breakdown of routine and deferred maintenance spending, in 2016, the Government Accountability Office found that from 2006 to 2015 the park service spent roughly $1 billion annually on all types of maintenance. During that period, total annual agency funding was approximately $3 billion. More recently, the Congressional Research Service has found that appropriations to the National Park Service’s budget accounts that help fund deferred maintenance projects have been increasing.

Visitors can help address maintenance needs.

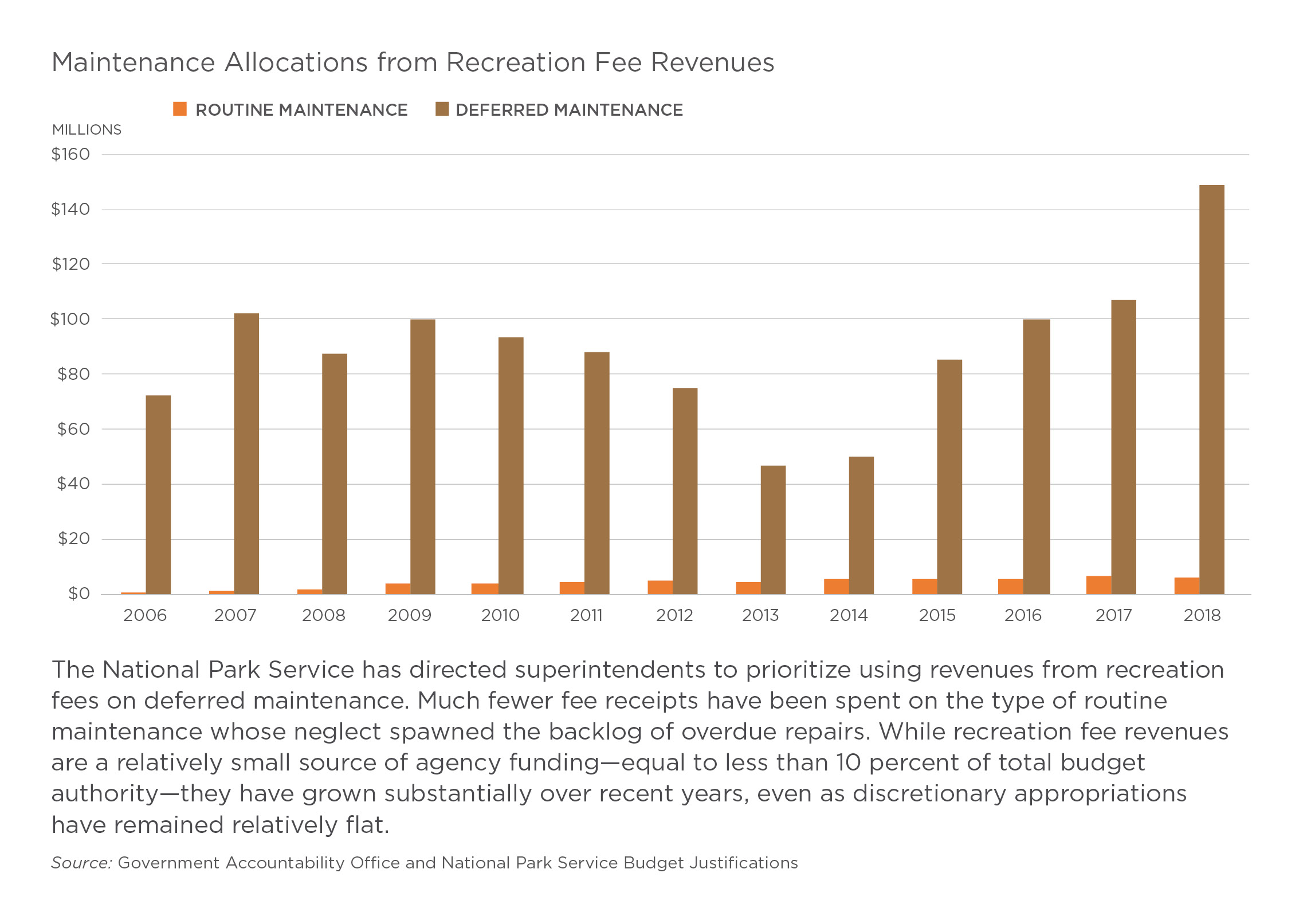

While discretionary appropriations are the main source of funds for maintenance, they are not the only source—recreation fee revenues also have a role. When visitors pay for entry to a park or use of amenities like campgrounds, parks retain most of the proceeds. Fee receipts across the park system have grown rapidly over the past decade, partly due to increased visitation—a mixed blessing given that more visitors mean more impacts to parks. Agency policy, however, often prevents fee revenues from being spent on routine maintenance.

For one thing, the National Park Service directs park managers to spend 55 percent of fee receipts on deferred maintenance. That directive means that growth in fee revenues has generated more funding for overdue repairs but contributed much less to regular maintenance. More generally, while fee expenditure authority clearly permits superintendents to address one-time projects, there is much more uncertainty when it comes to recurring expenses. The consequence is that fee revenues generally are not used for purposes such as regular maintenance of visitor facilities, road work that can prevent long-term damage, or permanent employees that conduct and oversee routine maintenance.

In 2018, for instance, parks spent $148.7 million of recreation fee receipts on deferred maintenance but just $6.3 million of them on routine maintenance, a 23-fold difference. The emphasis on deferred maintenance and one-off projects comes at the expense of cyclic maintenance and threatens to exacerbate the underlying issue.

Perverse incentives can compound maintenance challenges.

The restrictions on the use of fee revenues combined with the lack of funding for routine maintenance have created incentives to let maintenance lapse. Once maintenance becomes deferred, park superintendents can more readily address it with fee revenues. It’s an illogical and counterproductive result that increases the overall maintenance burden and costs parks, visitors, and taxpayers more in the end.

If unaddressed, these backward incentives could be exacerbated by the Great American Outdoors Act. The act will provide funding dedicated to deferred maintenance, but it will not be enough to overcome the entire backlog, nor will it address the fundamental cyclic maintenance issue. Providing billions of dollars to shore up park assets makes sense only alongside a plan to protect the investments in repaired infrastructure through regular upkeep into the future.

Former chief of park facility management Tim Harvey has emphasized that the “underfunding of park operations” caused the accumulation of deferred maintenance and suggested that Congress identify ways to maintain the infrastructure that will be restored with funds from the act. “So you build a new building,” Harvey has said, “well you’ve got to pay for the heating, the cooling, the lighting, the cleaning, staffing, … cleaning gutters, doing painting, cleaning carpets.”

Any new asset, whether a recently opened visitor center or an entirely new park unit, should only be added if it can be accompanied by a fiscal strategy to maintain it sustainably. While new park facilities may have fewer maintenance needs than aging infrastructure, adding to the system stretches the agency’s budget for routine maintenance more thinly. It makes no sense to continue to add to the system in a fiscally unsustainable manner, especially given that the agency cannot properly maintain its existing assets.

On-the-ground knowledge from park staff is valuable.

Park superintendents have good information about their own maintenance needs and how to meet them, but they need the proper resources and adequate flexibility to address them.

Estimating costs to maintain unique assets that range from one-of-a-kind historic structures to hiking trails is inherently imprecise. The Interior Department has noted that “due to the scope, nature, and variety” of assets it administers, “as well as the nature of deferred maintenance itself, exact estimates are very difficult to determine.” Yet even if a park unit’s report on asset conditions cannot guarantee that every line item is up to date and accurate, that unit’s superintendent is likely to know which maintenance projects should be prioritized if funding materialized. Local staff have on-the-ground context that appropriators and bureaucrats lack, so it makes sense to empower them to make more decisions about how to balance maintenance needs.

Congressional appropriations have proven inadequate to address the park system’s underlying maintenance challenge so far, but various strategies can help provide more funding and flexibility to take care of parks now and into the future.

Maintaining Parks for the Long Haul

To care for parks over the long run, superintendents and their staff need dependable, recurring funding that they can put to use where most needed. While Congress should prioritize maintenance of existing parks to help ensure the agency avoids a new backlog, there are additional ways to increase funding available for maintenance. If parks can reduce the overall amount of maintenance required by disposing of infrastructure assets that no longer justify their costs, then their funding will go even further.

Recommendations:

Prioritize the maintenance of existing parks over adding new units to the system.

Nearly three decades ago, National Park Service Director James Ridenour worried that the agency was adding sites popular with politicians at the expense of failing to maintain existing parks. “We’re not doing an adequate job of taking care of our crown jewels,” Ridenour said in 1991. “To see us further expand into areas of questionable national significance, while not taking care of areas that are significant, seems to me a foolish step to make.” Since then, the number of park units has steadily increased. In 2016, the Government Accountability Office noted that some National Park Service officials echoed similar concerns as Ridenour given that growing the number of parks “meant that the agency’s appropriations had to be divided among an increasing number of units.” Opening new parks is more conspicuous and popular than repairing assets like wastewater systems, but legislators and the agency should solve the underlying maintenance issue before Congress adds new parks to the system.

Improve flexibility in setting and spending recreation fees so that parks can harness the revenues they generate more effectively.

Fee collections will never be able to address the immense maintenance backlogs that have already accumulated at many parks, which can run hundreds of millions of dollars. Granting superintendents more authority and flexibility to modify fee structures and spend the revenues they generate, however, can help prevent the next backlogs from forming. Agency oversight will remain imperative, and superintendents should be held accountable for their decisions—particularly if they seek to build new assets without a sustainable fiscal strategy to maintain them. But devolving authority to the local level allows managers to take advantage of their on-the-ground knowledge, and it can ultimately increase accountability because it is clear who is responsible for spending decisions.

In the past, onerous and time-consuming processes required to adjust national park fees have discouraged units from altering fee structures. Similarly, while well intentioned, the internal National Park Service directive to spend 55 percent of fee revenue on deferred maintenance prevents local park superintendents from determining what type of maintenance should be prioritized, and it perversely encourages managers to allow maintenance to become deferred. Uncertainty over authority to spend fees on recurring expenses can also worsen the overall challenge by hamstringing cyclic maintenance. Agency policy should allow local managers to use the resources their sites generate to address their greatest needs, which could mean addressing routine maintenance before it ever becomes overdue.

Contract out services and activities where feasible and appropriate.

More than 1,000 campgrounds and recreation areas administered by the Forest Service are operated by private concessioners that collect visitor fees, perform routine maintenance of resources and facilities, and return a portion of their receipts back to the agency. By contrast, concession operations in national parks are generally limited to lodges, retail stores, and restaurants.

Warren Meyer, owner of a company that operates more than 100 federal and state recreation sites, has testified to Congress that Forest Service campgrounds operated by concessioners “have proven to be 30-70 percent less expensive than agency operations of the same campgrounds, often converting recreation areas that consume general funds to ones that pay their own way and actually create concession fees for the government.” He also noted that concession-operated sites tend to pass on cost savings to visitors in the form of lower fees and that they have greater flexibility in adopting new technology like cell phone payments. Concessioners also guarantee continued operation of sites during government hiring freezes or shutdowns and often make improvements to infrastructure such as sewer and water systems and basic amenities like restrooms, picnic areas, and RV dump sites.

The National Park Service should explore opportunities to contract out more routine operations, such as running campgrounds, to private operators. Given the number of unique management needs warranted by most national parks, the agency would benefit by focusing its resources on mission-specific tasks and leaving basic operations such as cleaning campground bathrooms to private operators. By doing so, the agency could alleviate maintenance needs, lower operations costs, and increase visitor benefits, while maintaining federal oversight.

Calculate whether certain infrastructure assets no longer justify maintenance costs and qualify for disposal.

The National Park Service uses two tools to assess the priority and condition of its assets, including roads, buildings, trails, and other infrastructure. The asset priority index ranks the relative importance of an asset according to whether it has substitutes and how much it contributes to resource preservation, visitor use, and operations. The facility condition index is a ratio of the cost of repairs for a given asset relative to its current replacement value. A clear-eyed comparison of the relative priorities and conditions of park assets can reveal if some qualify for disposal, whether through transfer, demolition, return to nature, or otherwise, which could reduce cyclic as well as deferred maintenance needs.

The most obvious candidates for disposal are assets that either have become low priority, have high repair costs relative to asset value, or both. For instance, a park’s least-popular campground could be rendered superfluous if visitor patterns shift significantly. If the campground requires expensive maintenance or repairs, it may be an even stronger candidate for disposal. A 2019 study commissioned by Pew Charitable Trusts estimated that demolishing inessential buildings and allowing nature to reclaim low-priority trails, roads, and parking lots could save parks more than $300 million in deferred maintenance costs over a decade. Disposing of such assets would also remove their recurring maintenance costs from the operations budgets of parks. While disposal of underused or dilapidated assets may not always be politically popular, it would allow budget dollars to be spent on other priorities, empowering park managers and ultimately benefiting visitors.

Implement strategies to maintain roads in a financially sustainable way.

The National Park Service maintains approximately 5,690 miles of paved roads, 990 paved miles of parking areas, 1,451 bridges, and 63 tunnels. Funding from the Department of Transportation helps maintain such infrastructure through the Federal Lands Transportation Program and the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act, the latter of which funded more than half of the agency’s transportation improvements in fiscal year 2019.

While the agency should aim to maintain all types of park assets sustainably, roads represent a huge portion of the overall maintenance challenge. Transportation infrastructure has consistently accounted for roughly half of the National Park Service’s deferred maintenance over recent years. Three agency-managed parkways total nearly $1.5 billion in deferred maintenance—practically one-eighth of all deferred maintenance in parks. Today, numerous roads within the park system are far from the panoramic routes they originally were and instead serve as local or regional connector roads that happen to bisect national parks or, in some cases, even function more as a commuter highway than as a scenic byway.

The National Park Service may no longer be the most appropriate entity to manage and maintain such roads, and the agency should explore transferring responsibility for them to state or local entities where appropriate and feasible. Pew Charitable Trusts has identified more than 2,600 road miles that could be prime candidates and whose transfer could reduce agency deferred maintenance by more than $1 billion. Where outright transfer of road authority is not feasible, there may be opportunities to create cooperative arrangements to share responsibilities and costs with outside entities. For roads administered by parks, the agency could explore investments in long-term technologies such as perpetual pavement, a type of durable asphalt that can increase road lifecycles and reduce long-run costs.

Legislators acknowledged that road maintenance in parks should not fall entirely to park-related funding when they dictated that at least 65 percent of deferred maintenance funding from the Great American Outdoors Act’s restoration fund go toward non-transportation related projects. Strategic approaches to tackling road-related challenges would allow the agency to reduce its maintenance needs and put resources to use elsewhere.

Conclusion

After years of deferred maintenance accumulating in national parks, policymakers have devoted significant funds to the backlog. But the fundamental issue of neglecting routine maintenance remains. Smart reforms to maintenance policy can better align incentives and empower managers to care for national parks over the long run, helping ensure parks can avoid accumulating new backlogs in the future.

Download the full report, including endnotes and references.