This article was originally published in The Hill.

This week, Congressional Democrats announced details about their vision for a Civilian Climate Corps, a Biden administration-backed initiative that aims to create government jobs conserving public lands and investing in climate resiliency. At the time, wildfires raged across the western United States, pouring out smoke and haze that now stretches from Oregon all the way to the East Coast.

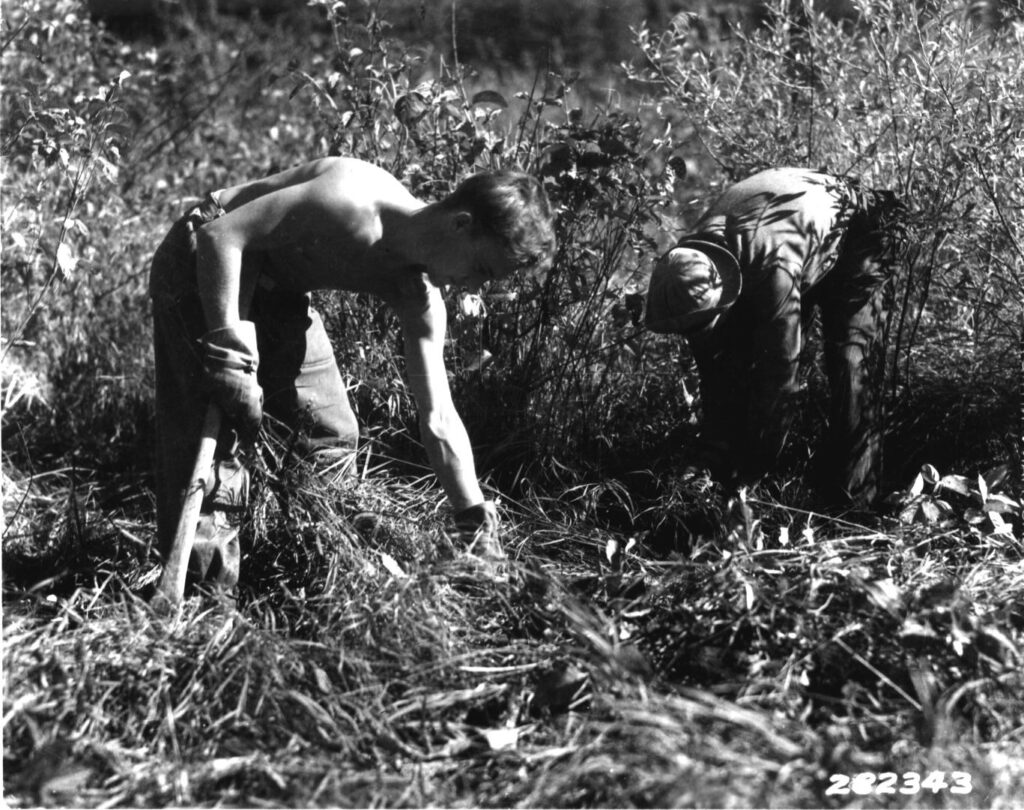

Corps programs may be a way to get boots on the ground in the form of young people eager to tackle outdoor projects. But they cannot address the underlying obstacles to conserving public lands that have led to problems like our current wildfire crisis. Those obstacles include regulatory uncertainty that hamstrings forest restoration projects, poor incentives that have resulted in neglect of public lands, and litigation risks that stymie big projects by federal agencies and their private partners alike. Reforms to address these barriers and make it easier to engage the private sector are needed to improve our ability to conserve and restore public lands, whether undertaken by members of a new corps program or otherwise.

Federal agencies face mounting conservation challenges, notably the worsening wildfire crisis and neglected public land maintenance. These issues won’t go away on their own—they will require active effort to resolve. But several key obstacles hinder federal land managers, along with their state, tribal and private partners, from addressing the challenges.

The Forest Service reports a backlog of 80 million acres in need of restoration and 63 million acres facing high or very high risk of fire. Yet, recently the agency has been able to reduce fuels on just 1.4 million acres per year. At that pace, it would take decades to address the current buildup, all the while leaving air and water quality, ecosystems, and our communities at risk.

A recent PERC report examines obstacles that limit the pace and scale of forest restoration on the ground, such as the regulatory uncertainty and litigation risk that can delay for years projects that would mitigate wildfire risk. This idea is reflected in new legislation proposed by Rep.Bruce Westerman (R-Ark.), the Resilient Federal Forests Act, which seeks to expand categorical exclusions to help streamline much-needed forest work. Given the size of the task, the research also highlights the need to better engage partners to help accomplish the effort—a strategy with great potential given the numerous states, tribes, conservation groups, and private companies that have huge incentives to help make forests healthy and avoid the devastation wildfires wreak.

When it comes to national parks and other federal recreation lands, record crowds are showing the immense value of these resources—and severely straining public lands infrastructure. In total, public lands are saddled with approximately $20 billion in overdue maintenance. The National Park Service alone faces a nearly $12 billion maintenance backlog, including care for 21,000 miles of trails and 25,000 buildings.

The Great American Outdoors Act, passed last year, will fund a portion of these needs. But as PERC research has noted, such measures, while helpful, do not address the underlying neglect that gave rise to the backlog and will not alone keep it from recurring. Creative approaches to harnessing revenues from visitors could help address today’s maintenance before it becomes tomorrow’s problem, as could other innovative, market-based approaches to managing our recreation lands.

Similar stories of conservation needs can be told regarding water, wildlife, abandoned mine cleanup, and countless other environmental areas. Tackling these challenges will require resolving the underlying obstacles. And given the enormity of the conservation tasks facing public lands, leveraging the private sector will be crucial, whether through partnerships that increase capacity to restore public forestland or concessioner models that save federal dollars and free agencies to focus on mission-specific work.

Establishing a new corps program will not resolve fundamental obstacles that hinder broad conservation and restoration work. Efforts to expand our conservation capacity and bolster climate resilience must include reforms to address these barriers and engage the private sector, making it easier for conservationists, including corps members, to make lasting improvements on the ground.