This special issue of PERC Reports explores the thorny issues of forest management, wildfire mitigation, and regulatory reform. Read the full issue.

As the Caldor Fire made its menacing march toward South Lake Tahoe last summer, it burned more than 200,000 acres and destroyed over 700 homes. While the effects of the fire were tragic, greater tragedy was averted when firefighters steered the fire away from the city and to an area where fuel loads had been reduced through active forest management. This tamed the fire enough for firefighters to fight it directly and get it under control.

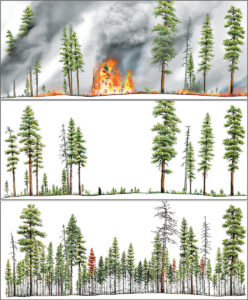

South Lake Tahoe was not the only area where recent management actions helped stave off disaster in 2021. In Oregon, the Bootleg Fire burned more than 400,000 acres, producing flames over 200 feet high. Katie Sauerbrey, a fire manager for the Nature Conservancy, told The New York Times that it was “the most extreme fire behavior I had ever seen in my career.” But when the fire passed from the Fremont National Forest to the conservancy’s Sycan Marsh Preserve, the catastrophic wildfire changed dramatically. In an area that the conservancy had thinned and then managed with prescribed burns, the flames shrank to a mere four feet, dropping from the forest canopy to the ground, where they were easier to control.

Forest restoration—the use of mechanical thinning, prescribed fire, replanting, and erosion-control techniques—can reduce wildfire damage while promoting more resilient forests.

These and other high-profile examples of forest restoration projects reducing the consequences of wildfires have sparked bipartisan interest in ramping up those projects. In January, the U.S. Forest Service announced a 10-year strategy to implement strategic restoration projects—including mechanical thinning and prescribed burns—on 50 million acres (over and above its normal restoration levels) of federal, state, and private land where fire risks and threats to communities are greatest. This ambitious plan relies on roughly $1.5 billion that Congress appropriated in last year’s infrastructure legislation for mechanical thinning, prescribed fire, and post-fire recovery projects, and it calls for spending a total of $50 billion over the next decade.

But carrying out the Forest Service’s ambitious plan in a mere decade will require more than increased funding. It will require Congress and the Forest Service to address policy obstacles that have sapped the agency’s ability to deliver forest restoration at scale and on time. And it will also require greater engagement with states, tribes, and private partners to capitalize on their local knowledge and capacity to perform restoration projects.

A Backlog Fuels Fire

Fire is nothing new to western forests, which are adapted to flames due to climate, terrain, and indigenous tribes’ use of controlled fire for millennia. However, recent catastrophic wildfires are far more destructive than historical fire regimes. They are more likely to threaten old-growth trees, wipe out habitat for wildlife, and cause erosion that degrades watersheds and fish habitat. And due to growing populations near forests, modern fires also threaten communities and property in ways not seen before.

Forest restoration—the use of mechanical thinning, prescribed fire, replanting, and erosion-control techniques—can reduce wildfire damage while promoting more resilient forests. The Forest Service reports an 80 million-acre backlog in needed restoration, more than 40 percent of the 193 million acres under the agency’s control. The agency deems 63 million of those acres to be at high or very high risk of burning. Add to this the 54 million acres managed by the Department of the Interior and the total area of federal land facing high or very high fire risks is larger than the state of California.

Wildfires are not limited to federal forests. But national forests nonetheless play an outsized role due to their concentration in the West as well as the conditions throughout many of them. While the federal government owns less than a third of forests nationwide, it controls roughly half the forested land in Arizona and Washington, 60 percent in California, Colorado, Montana, and Oregon, and 80 percent in Idaho and Nevada. Due to this concentration and differences in how federal and private lands are managed, the total area of federal land facing high or very high wildfire risks far exceeds the 52 million private acres facing such risks. And federal lands are consistently overrepresented in the total area burned, including 75 percent of the acreage burned in the West during 2020.

Power in Partnerships

While the infrastructure bill’s $1.5 billion for forest management is a lot of money, it goes quickly when spread across 50 or 80 million acres. The cost of mechanical treatments and prescribed burns varies among different forest types and landscapes, but $1,000 per acre is a commonly used average. The infrastructure bill, however, represents only about $30 per acre toward the Forest Service’s 10-year goal and only $20 per acre toward the larger forest restoration backlog. Thus, it will be essential that the agency work with outside partners to stretch the money further and, through collaboration, overcome conflict.

Such partnerships are also critical because the Forest Service’s capacity to increase forest restoration is limited. Perhaps understandably, the agency has historically responded to fire’s political salience by shifting resources to suppression. The programs that fell victim of the agency’s “fire borrowing,” a euphemism for raiding other programs to fund firefighting efforts, were “often those that improve the health and resilience of our forested landscapes and mitigate the potential for wildland fire in future years” according to a 2015 Forest Service report. “[I]t is readily apparent that the Forest Service cannot meet national direction to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration with its current workforce,” concludes a 2019 survey of Forest Service managers.

States, tribes, and private parties are motivated to help due to the significant benefits forests provide, including clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities. For instance, the National Forest Foundation and Salt River Project, a water utility, have formed the Northern Arizona Forest Fund to perform restoration in five national forests. Since 2015, the fund has raised more than $6.2 million from a diverse group of supporters, including the Arizona Department of Fish and Wildlife, the cities of Scottsdale and Phoenix, Coca-Cola, businesses dependent on outdoor recreation, and conservation groups.

From the perspective of these supporters, paying for forest restoration today is much better than suffering the consequences of wildfire tomorrow. Thanks to these contributions, as well as volunteer time and expertise, the Northern Arizona Forest Fund has implemented fuel reduction projects on 13,600 acres, improved 2,600 acres of wetlands, planted 90,000 trees, and reduced erosion along 170 miles of roads and trails. As J.D. Tuccille reports, viable markets for small-diameter timber and brush could empower similar collaborations to restore even more forest land.

In many communities, raising large sums upfront for the promise of future benefits may be difficult. To solve this problem, two nonprofit organizations, Blue Forest and the World Resources Institute, have launched forest resilience bonds, which raise private capital to pay for forest restoration and allow beneficiaries to pay investors back over time as benefits are achieved. In 2018, the groups raised $4 million from investors to implement the first forest resilience bond, in Tahoe National Forest, with the State of California and the Yuba Water Agency signing on to repay the bond. The bond has enabled restoration projects covering 7,000 acres, completing in four years work that the Forest Service expected to take at least a decade.

With this proof of concept, Blue Forest is scaling up the innovation substantially. It is currently raising $25 million for a second bond, to restore more than 28,000 acres of Tahoe National Forest. And it has three more bonds in the pipeline, which could help restore tens of thousands more acres across the West.

Partnering with local governments also presents an opportunity to stretch dollars further while obtaining the benefits of local knowledge and enthusiasm. As Hannah Downey explains, under the Forest Service’s Good Neighbor program, states, tribes, and counties can take the lead on planning and implementing timber sales and stewardship contracts. In 2020, Good Neighbor Authority projects constituted 11 percent of all timber sales in Forest Service Region 1, which covers Montana, North Dakota, and parts of Idaho and South Dakota. The program lets states keep receipts from timber contracts to fund additional restoration projects. But tribes and counties are arbitrarily excluded from this part of the program.

Restoration Meets Red Tape

Ultimately, there may be a long road from the Forest Service announcing its ambitious 10-year plan and Congress appropriating money to the agency and partners increasing on-the-ground work. This is because several policy obstacles hinder the Forest Service’s ability to ramp up restoration, a challenge PERC explored in its 2021 report “Fix America’s Forests.”

For one, forest restoration projects must be reviewed under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Depending on the extent of anticipated impacts, NEPA may require the Forest Service to analyze a project through, in order of increasing complexity and expense, a categorical exclusion, environmental assessment, or environmental impact statement. The agency may also need to develop a range of alternatives to the project and analyze their impacts. The resulting documents routinely span hundreds of pages of dense text, with appendices spanning another thousand pages or more.

While well intentioned, NEPA reviews can increase project costs significantly and inject substantial delays. According to a new report by PERC Senior Research Fellows Eric Edwards and Sara Sutherland, “Does Environmental Review Worsen the Wildfire Crisis?,” the average time from when NEPA review begins and on-the-ground treatment begins is 3.6 years for mechanical thinning and 4.7 years for prescribed burns, with 476 and 463 days respectively spent generating required NEPA analysis.

The key factor for determining how long it takes to review a forest restoration project under NEPA is the type of analysis required. For a project analyzed under a categorical exclusion, the NEPA analysis takes approximately seven months on average. If a project requires an environmental assessment, then the average time required will increase by nine months compared to a categorical exclusion. And if it requires an environmental impact statement, the time required increases by two years on average compared to a categorical exclusion. Forest restoration projects are more likely than other Forest Service activities to require an environmental assessment or environmental impact statement, making NEPA a more significant challenge for forest restoration.

States, tribes, and private parties are motivated to help due to the significant benefits forests provide, including clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities. From the perspective of these supporters, paying for forest restoration today is much better than suffering the consequences of wildfire tomorrow.

Unless these timelines can be reduced, they represent a significant obstacle to achieving the Forest Service’s 10-year strategy. The agency anticipates focusing on “shovel-ready” projects—which have already undergone NEPA review—in years one and two. But it may be years before the plan results in new projects ready to be implemented. If, for instance, the Forest Service hopes to carry out ambitious prescribed burns, the type of project most likely to require an environmental impact statement, it has less than three years to develop those plans and begin the NEPA process if it wants to actually implement the prescribed burns before the decade is up.

In many western forests, the Endangered Species Act presents an additional complexity. If a project may affect a species or its critical habitat, the agency must consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to identify ways that impacts to the species can be avoided or mitigated. The law’s intention is good, but the means of pursuing it presents underappreciated risks. Consider the Forest Service’s ill-fated Pumice Project, which was proposed in 2011 to reduce wildfire risks on nearly 10,000 acres of Klamath National Forest. The project faced a decade of objections from local environmental organizations over alleged impacts to the northern spotted owl, a species listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Ultimately, 2021’s Antelope Fire “burned through the site before a single chainsaw touched a tree, destroying the owl habitat that the environmental groups were trying to save,” according to a recent report by the Sacramento Bee. Drew Stroberg, a district ranger in the Klamath National Forest, lamented the time and resources sunk “into kind of bulletproofing” the environmental analyses, observing that “now, they might as well be in the trash can.”

In much of the West, delays can give the act a cascading effect. If a new species is listed or critical habitat designated in the years between an environmental review is done and a project is implemented, the agency can be forced to stop on-the-ground work and redo the analysis. Under the Ninth Circuit’s 2015 Cottonwood decision, such regulatory changes require the Forest Service to restart consultation with the Fish and Wildlife Service at the forest plan level, then restart consultation for individual projects before proceeding. The Obama administration urged the Supreme Court to reverse Cottonwood, arguing that the rule “has the potential to cripple the Forest Service.”

Litigation is another obstacle—one that compounds the others. The Forest Service faces more NEPA lawsuits than any other federal agency. Roughly two-thirds of the lawsuits challenging Forest Service projects from 2005 to 2019 targeted forest restoration projects. The consequences of litigation, however, have not been evenly felt. Eighty-five percent of cases were filed in courts within the Ninth Circuit. Nearly half were filed in only two district courts: the District of Montana and the Eastern District of California, both areas facing significant wildfire risks.

Litigation risks have a cascading effect. Agency personnel report that they respond to the perceived threat by trying to “litigation proof” NEPA and Endangered Species Act reviews. According to PERC’s research, mechanical treatments requiring an environmental impact statement that is litigated take nearly seven years before the treatment begins, compared to five for those that aren’t litigated. For prescribed fires, these timelines are 9.4 years and 6.8 years, respectively.

Conflict over the Bozeman Municipal Watershed Project in Montana presents a worst-case scenario of bureaucracy and litigation compounding the effects of each other. In 2004, the Forest Service determined that wildfire risks in an area of the Custer-Gallatin National Forest threatened 80 percent of the city of Bozeman’s drinking water supply and required urgent action.

The Forest Service spent three years preparing a draft NEPA document. While the agency was working to finalize that document, a federal court overturned the delisting of the local grizzly bear population, triggering the agency’s duty to consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service. In 2010, the Forest Service released its NEPA and Endangered Species Act analysis and approved the project. Administrative challenges were filed. While those were pending, the Ninth Circuit decided several unrelated cases that caused the agency to revise its analysis again to address perceived litigation risks.

After that additional review was complete, a lawsuit was filed. While that was pending, critical habitat was designated for the Canada lynx, which led the Ninth Circuit to hold in Cottonwood that projects like the Bozeman Municipal Watershed Project required an additional round of analysis and resulted in a district court enjoining the project. After the Forest Service completed this additional analysis, the district court lifted its injunction in 2020, allowing the project to finally move forward.

Such delays could perhaps be justified if they resulted in material improvements to a seriously flawed project. But that wasn’t the case with the Bozeman project, which remains the same as it was when originally proposed more than 15 years ago. It’s questionable what, if any, benefit the public got from the protracted litigation and bureaucratic morass.

Clearing the Logjam

If the backlog is going to be overcome, more innovative public-private partnerships and policy reforms are needed. Such reforms should seek to encourage collaboration, rather than conflict, to increase the Forest Service’s flexibility to partner with states, tribes, and private parties, and to facilitate market reforms that can make forest restoration cheaper, or even profitable. With fire seasons growing longer, millions of acres burning every year, and more people and homes at risk, the stakes could not be greater.