Wild horses have a way of capturing our imagination. They have come to symbolize the American West, evoking a sense of freedom, beauty, and rugged resilience. For many, these iconic creatures have become much more than just animals—they are a part of our heritage and our ethos.

For Ryane Nicole, this sentiment surely holds true. Nicole adopted her first wild mustang from the Bureau of Land Management in 2020. For more than half a century, the agency has been charged with protecting tens of thousands of wild horses that roam public lands in the West. “I have had my life changed by a mustang that I named Aslan,” Nicole says. “Not only is she a sweet horse, but she is a jumper and participated in her first rodeo last summer with my daughter barrel racing. She loves riding in the mountains.”

Aslan was one of many wild horses that compete not just with wildlife for water and forage on public rangelands plagued by drought but also with an ever-expanding population of other wild horses and burros. After struggling on public lands for years, Aslan was relocated to a BLM holding facility in one of the agency’s regular roundups that gather and remove horses from ecologically stressed, overpopulated rangelands. Thankfully, Nicole and Aslan found each other, and she gave the wild but promising mustang a second chance at life.

Across much of the West, wild horses and burros struggle for survival on federally managed lands. The challenge is complex, and solutions are not uniform or final. But one new strategy in particular, an adoption incentive program, has relieved some of the pressure on public lands over recent years by helping place more animals like Aslan into private homes.

The program is unique in that, rather than only charging an adoption fee, it embraces market logic by paying adopters to take on a wild horse. This simple idea unlocked the power of incentives to help address an ecological and fiscal crisis.

Challenges on the Range

When thinking of the American West, certain images come to mind: rolling prairies, towering snow-capped mountains, roaming wildlife, and, maybe most iconically, wild horses. We’ve all seen western classics that feature majestic stallions galloping freely across the plains, their manes blowing in the wind, their coats shining as their heels kick up clouds of dust. But the tranquil depiction might be overly romanticized.

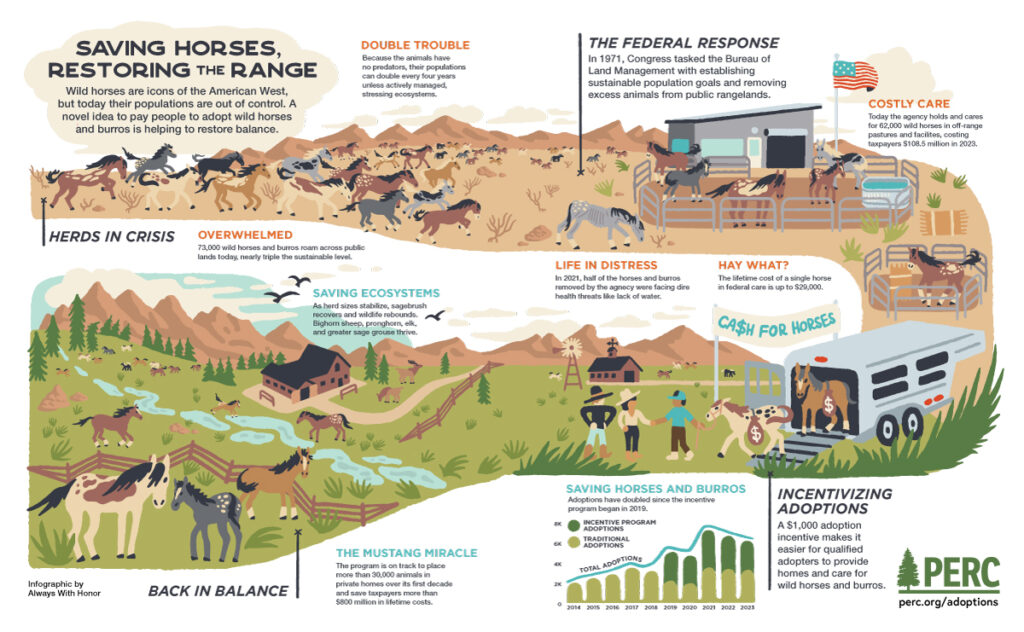

Domestic horses were introduced by Spanish explorers in the 16th century. Native peoples and European settlers alike adopted them as draft and pack animals. Eventually, feral populations emerged, expanded, and became just as enmeshed in natural ecosystems as native species. By the 1970s, however, pressure from hunting for sport and commercial uses had dwindled their numbers to roughly 25,000. Congress responded by passing the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act. This legislation made it illegal to “kill or harass” wild horses and burros on public lands and charged the Interior and Agriculture Departments with the animals’ protection. With new legal safeguards in place and no natural predators, populations soared.

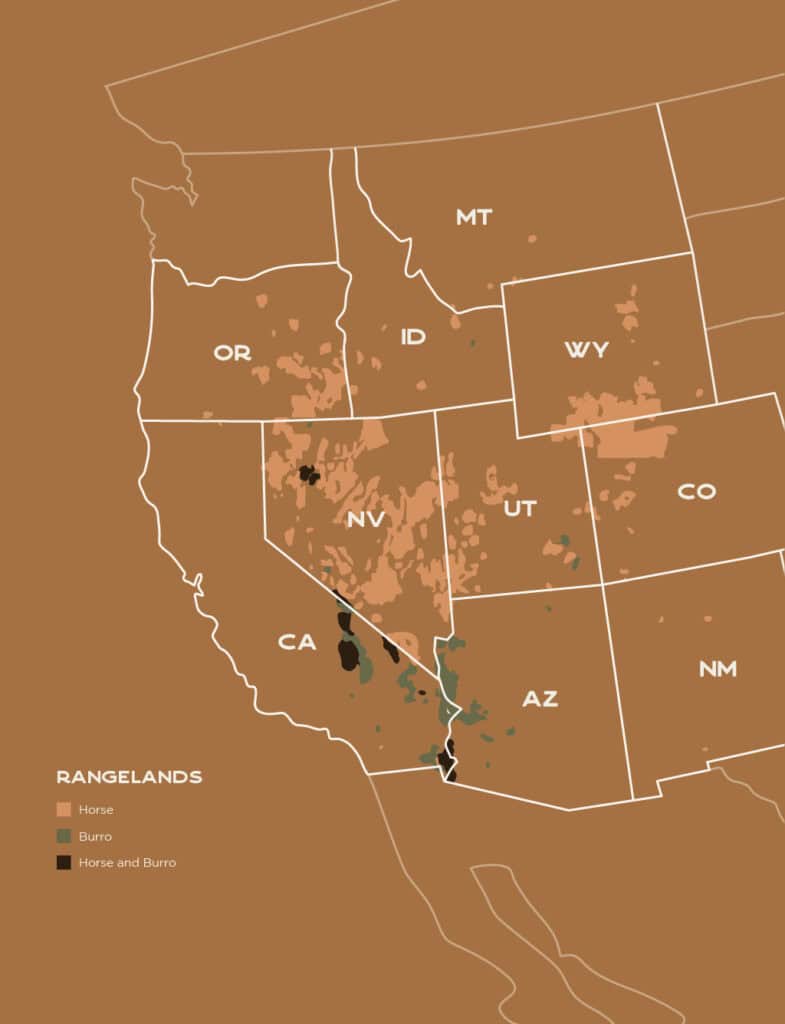

The animals’ feral status, however, makes them a complicated species to manage. Wild horses are not considered livestock and so cannot be privately managed, nor are they considered game animals and, therefore, are not managed by state wildlife agencies. Instead, they are managed by the federal agencies whose land they occupy, principally the Bureau of Land Management. The agency faces the unique challenge of managing 177 herds of wild horses and burros across 27 million acres in 10 western states.

Today, the BLM estimates there are 73,520 wild horses and burros on its rangelands. The agency sets target population thresholds for each herd, known as “appropriate management levels.” The national appropriate management level is approximately 27,000, making current populations nearly three times the sustainable target. And this number doesn’t capture the full picture, as there are wild horses and burros found on other federal lands managed by the U.S. Forest Service and on Indian reservations. If left unchecked, populations can double every four years, making the situation an overwhelming and seemingly intractable management problem.

Soaring populations combined with years of drought have set the stage for broader ecological disaster. More horses on the range means more competition for forage and water, leaving many animals in a perilous position. In a stark example of how grave it can get, nearly 200 horses were found dead in 2018 in Arizona on the western edge of the Navajo Nation. The desperate animals were found circled around a dry watering hole. “These animals were searching for water to stay alive,” said Navajo Nation Vice President Jonathan Nez. “In the process, they unfortunately burrowed themselves into the mud and couldn’t escape because they were so weak.”

Overpopulation poses serious challenges not just to the species in question, but to the broader ecosystem they are a part of. These animals roam tens of millions of acres across the West, competing with other wildlife, livestock, and even humans for space, forage, and water. This challenge impacts wildlife as diverse as sage grouse, elk, and trout. Research from U.S. Geological Survey scientists, for example, found that by 2034 greater sage grouse populations could decline by more than 70 percent within free-roaming horse-occupied areas if their populations continue to grow unchecked. The Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation has also raised concerns about the impact of expanding horse populations on forage competition with elk and other big-game species. Likewise, competition for limited resources in overpopulated areas can damage mountain streams that are home to native trout species.

Searching for Solutions

Historically, the BLM has had two primary solutions for addressing this problem: roundups and fertility control through immunocontraception. The former involves hazing horses, sometimes with helicopters, to gather them from the range and then transport the animals to federally managed holding facilities. The latter involves either darting mares with fertility control drugs or executing a “catch-treat-hold-release” operation, which requires gathering horses, vaccinating them, holding them for 30 days, administering a booster shot, and then releasing them back onto the range. Administering a dose of fertility control costs approximately $2,500 per mare. The agency focuses on herds that are close to a sustainable size, so as to maximize the effectiveness of the fertility treatment, but shots are effective only for a few years. Considering the scale of the challenge, immunocontraception is a slow and expensive process. In 2022, the agency treated 1,622 mares with fertility controls—a record number, but still only about 4 percent of all wild mares.

Roundups that result in holding wild horses and burros in federal facilities are also an expensive endeavor. In 2023, taxpayers spent $109 million to hold roughly 62,000 wild equines off pasture. Holding horses eats up 70 percent of the program’s budget, which means relatively few resources for other population-management measures.

Once wild horses and burros are in BLM care, the principal way they move out of federal holding facilities is through adoption into private homes. Historically, the animals were auctioned off at a minimum bid of $125. Adoptions occurred, but not at a rate that could keep up with the growth of horses in holding facilities. There was no shortage of wild horses, but there appeared to be a shortage of buyers.

Rather than charging people to adopt wild horses, the PERC fellows flipped the adoption script and proposed that the government instead pay adopters.

Then in a 2016 article in the Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, PERC fellows Randy Rucker, Timothy Fitzgerald, and Vanessa Elizondo posed a straightforward question. Why are taxpayers spending tens of thousands of dollars per head to care for horses whose value is so low that no qualified private horse buyer is willing to offer $125 for one? With oversupply and limited demand, the researchers reasoned that a financial incentive was likely the best way to motivate potential adopters. Rather than charging people to adopt wild horses, the PERC fellows flipped the adoption script and proposed that the government instead pay adopters. Their research estimated that a financial incentive for adoptions could have reduced the BLM’s wild horse and burro program costs by as much as $452 million over the previous 25 years.

By 2019, the bureau had embraced a version of the idea, and its adoption incentive program was born. Today, adopters pay a $125 adoption fee but are eligible to receive $1,000 to help cover the costs of taking on the animal. The $1,000 payment, the thinking goes, offers would-be adopters an incentive to take a chance on an untrained, wild mustang. (The BLM partners with organizations like Mustang Champions to help train wild horses in an effort to make them better candidates for adoption. Historically, such trained horses have been very attractive to adopters. As a result, the BLM excludes them from the incentive program.) The $1,000 payment is withheld until the bureau transfers title to an owner, which doesn’t take place until a full year after the adoption. The agency also requires a compliance inspection six months into the adoption process.

Five years later, the program appears to be a success. In a recent analysis of the adoption incentive program, PERC found that average annual adoptions have more than doubled compared to the five years prior to the program’s inception in 2019. To date, more than 15,000 wild horses and burros have been adopted through the program, and PERC’s analysis estimates that these incentive-program adoptions have saved taxpayers approximately $66 million in avoided holding costs.

In fact, the program is on track to adopt out 30,000 wild horses and burros into private homes over its first decade, saving an estimated $800 million over the lifetimes of those animals. The program, then, is making a meaningful contribution to reining in the wild horse crisis.

Addressing Concerns

Not everyone, however, is supportive of the program. Wild horse advocates—who generally oppose any removal of horses from public rangelands—have raised concerns that it could be exploited, fearing that once adopted horses are titled to private owners, the animals could be sold into supply chains that end at foreign slaughterhouses. (It’s worth noting that Congress prohibits agency funds from facilitating wild horse and burro slaughter, and wild horse adopters must agree not to facilitate slaughter, under penalty of prosecution. Relatedly, no horse slaughterhouses operate within the United States.) Groups such as the American Wild Horse Campaign claim that hundreds of animals adopted into private homes since 2019 were later sold at livestock auctions where buyers from slaughterhouses were allegedly in attendance. The activist group, however, has presented no direct evidence of such transactions taking place. The BLM maintains it has found no evidence of the program being abused.

Formerly wild horses being auctioned off for eventual slaughter would be a tragic outcome and certainly is one the bureau and conservationists should continue to work diligently to avoid. These concerns, however, do not negate the need to get overpopulated horses off the range nor the effectiveness of the adoption incentive program in helping achieve that goal.

The program is on track to adopt out 30,000 wild horses and burros into private homes over its first decade, saving an estimated $800 million over the lifetimes of those animals.

Some of these voices advocate for the program to be shuttered, but that would simply leave the bureau with fewer tools in its management toolkit. The challenge of overpopulation would persist, leaving horses, burros, elk, sage grouse, trout, and other wildlife locked in a competition for scarce resources. In the absence of an effective and affordable way to control rangeland populations of wild horses, roundups would still be necessary, and without adoptions to help offset costs, the expense of holding wild horses in off-range facilities would skyrocket. Instead, concerned wild horse advocates should focus on improving the program rather than seeking to dismantle it.

The program has always required adopters to sign an agreement declaring they “will provide humane care for any animals” they adopt and that they “will not knowingly sell or transfer ownership to any person or organization that intends to resell, trade, or give away such animals for slaughter or processing into commercial products.” In 2021, the BLM bolstered its enforcement to ensure bad actors can’t exploit the incentive program by updating several aspects of it and building in more safeguards. Previously adopters received half the $1,000 incentive payment at the time of the adoption and the other half once the title was handed over. Now, the incentive isn’t paid in full until up to 60 days after the title date. Additionally, adoptions now require sign-off by a veterinarian or BLM-authorized officer before the title is transferred and payment is made.

The BLM has made good-faith efforts to improve the program and protect the animals in its care. And the program itself has proven to be a valuable tool to relieve pressures in BLM holding facilities, saving taxpayer money and playing a part in improving rangeland conditions.

A New Path

Like the lion in Narnia, Aslan the horse didn’t succumb to her perilous circumstances. Adoption gave her a new lease on life, and today she has a loving home, is a trained jumper, and even rodeos. “I personally have seen the beauty in giving Aslan a second chance,” says Nicole. “She comes to my voice when I call her name. We have a unique bond that not only fills my heart, it connects my soul.”

The wild horse crisis won’t be resolved overnight. It will take many years to pare down the populations on our western rangelands, with the harmony of these fragile ecosystems shifting in response to factors ranging from climatic shifts to predator presence. Thankfully, though, tools like the adoption incentive program are helping alleviate the crisis, and, maybe most importantly, giving these beloved animals an opportunity to escape the perils of overpopulation by providing them a place to thrive off the range.

Ryane Nicole is a photographer with a passion for wild horse adoption.