The Salish Sea is a wild place. Stretching between Washington and British Columbia and extending to meet the Pacific Ocean, it is one of the largest inland seas in the world. And it teems with life—more than 3,000 species live in and around the sea.

I boarded the Glacier Spirit on a balmy summer day this year to spot some species that call the Salish Sea home. After sailing for a bit, I stood shoulder-to-shoulder with fellow wildlife enthusiasts as we stared across the Strait of Juan de Fuca at Vancouver Island. Filling the water between our drifting ship and the shore was a glorious sight: whales.

It was one of the most remarkable things I have ever witnessed on the ocean or land. Humpback whales surrounded our ship, surfacing, breathing, and diving in what could be mistaken for a choreographed dance. We counted at least 15 individuals, and there was nowhere to look without catching a glimpse of a spout breaking the surface or a flash of a whale tail.

Yet, as we started our slow trek back to port, something was still missing from the day’s adventure. I continued to scan the horizon for what I knew lurked beneath the waves: orcas.

The presence of orcas in the Salish Sea extends beyond what humans have documented, with much of our earliest knowledge coming from tribal legend. Coastal Native American tribes referred to the creatures as “blackfish,” a nod to their black-and-white coloring, and many tribes consider the animals sacred. Orcas have certainly earned their legendary status. They are massive creatures, growing to lengths of more than 30 feet, and can weigh up to 11 tons. Wild orcas can live incredibly long lives, with many living past 50 and some even as long as 80 years or more.

But lately, the orca population here, known as the Southern Residents, hasn’t been doing so well. Declining salmon numbers have played a role, as adequate food resources are critically important. Increased marine pollution, both in terms of chemicals and debris, means these orcas are also at risk of ingesting plastic, absorbing toxic chemicals, or becoming entangled in fishing gear. But one specific factor has become especially worrisome for this infamous orca population: noise from shipping vessels.

The Salish Sea

Masters of the Deep

It isn’t just their long lives or massive size that make orcas extraordinary. It’s their status on the food chain. Orcas are found in every ocean on the globe and are the top predator wherever they swim. While diets vary from pod to pod, orcas as a species have been documented consuming everything from blue whales to great white sharks to sea lions. Technically, orcas are the largest dolphin species, but their fearsome behavior as ravenous predators has earned them their “killer whale” nickname.

“They’re the apex predators of the ocean, just pure power,” mused Rachel Rodell, the Glacier Spirit’s onboard naturalist. “They’re exactly perfect for what they’re here to do and for this environment. We just get to observe.”

Puget Sound Express, the family-owned business that runs the Glacier Spirit, is just one of the many wildlife tour operators out on the sea. Wildlife enthusiasts flock to the area, and tourism is big business in the region. Many animal lovers like me come specifically hoping to glimpse one of the Southern Resident killer whales, some of the most famous orcas in the world.

Most Americans first came to know about orcas by seeing captured ones displayed at aquariums and marine parks or highlighted on film. Orca captures in the Pacific Northwest began in earnest in the 1960s, and many of the victims were Southern Residents. These captures continued until Washington state policymakers adopted legislation in 1971 implementing the first protections for orcas in American waters. Then, in 1972, Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act, effectively ending orca captures. At the time, 71 Southern Resident orcas remained in the Salish Sea.

Orca research also began in earnest in the mid-20th century, and Southern Residents quickly became the most studied population on the planet. Through this research, the world learned that Southern Residents stick to a rotation of seasonal ranges, usually form large family groups, and are smaller compared to other orca ecotypes, such as the transient population of so-called “Bigg’s orcas” that also frequent the Salish Sea. Residents are also often found close to shore, making them easily spotted from the coastline.

Bigg’s killer whales and Southern Resident killer whales may share the same sea at times, but that’s about the only thing they have in common. Transients are nomadic, tend to travel in small groups, and typically grow bigger than their resident cousins. A critical difference between the two ecotypes, however, is prey. Transients are mammal eaters; they traverse the Pacific Northwest coast hunting seals, sea lions, porpoises, and other mammals, but they eat no fish. Residents, on the other hand, eat Chinook salmon almost exclusively—and are highly reliant on sound because they use echolocation to hunt.

While other orca populations that had individuals taken during the captures of the 1960s have recovered, Southern Resident numbers are still lagging. Their population peaked in 1995 when nearly 100 individuals were documented in the Salish Sea, but numbers have since declined. Residents are the only orca ecotype listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. As of October 2024, only 73 documented individuals remained in the Salish Sea.

One reason resident orca numbers have plateaued is the difficulty of keeping calves alive. In 2018, the world heard the heartbreaking story of Tahlequah, a resident orca who swam more than 1,000 miles carrying the body of her dead calf. But Tahlequah is far from the only resident to have lost a calf. Michael Weiss, research director of the Center for Whale Research, estimates that half of the calves born to Southern Residents do not survive to see adulthood.

A Noisy Sea

Sailing through the Strait of Juan de Fuca may not guarantee any orca sightings, but it will ensure you see plenty of ships. During the afternoon I spent aboard the Glacier Spirit, we spotted every vessel you could imagine: other wildlife watchers, fishing boats, cruise liners, ferries, and even small military boats accompanying a massive nuclear submarine. But nothing stood out as much as the large industrial ships.

The first Salish Sea shipping ports were established in the 1800s. Like much of the rest of the world, the sea saw an uptick in commercial shipping beginning in the 1990s. A decade of trade liberalization resulted in freer markets and increased imports from nations like China. Global shipped cargo nearly tripled from 1990 to 2021, growing from 4 billion tons to nearly 11 billion tons. With more shipping came an increase in marine noise pollution, something that economist M. Scott Taylor has been studying for several years.

Taylor is a prominent economist at the University of Calgary known for his work on the environmental impacts of trade. Over his career, Taylor has used detailed empirical data and advanced economic modeling to analyze the environmental consequences of economic growth, especially in contexts where trade-driven resource use affects ecosystems. His work spans a range of topics, including the effects of globalization on wildlife populations. Recently, Taylor has turned his attention to the plight of the Southern Resident orcas, studying how shipping traffic in the Salish Sea has intensified noise pollution.

To examine how increased shipping noise might affect the Southern Residents, Taylor has assembled extensive datasets of vessel traffic in and through the Salish Sea. “I find that booming trade with Asia, post-1998, created a huge increase in vessel kilometers traveled” in critical habitat areas for the Southern Resident killer whales, Taylor explains. According to his research, kilometers traveled by commercial shipping vessels increased by more than a third in the two decades after 1998 compared to the two decades before that year. While the Salish Sea already sees thousands of annual commercial ship transits, shipping traffic is expected to grow significantly again in the coming years, thanks partly to several major fossil fuel projects that will begin exporting their products.

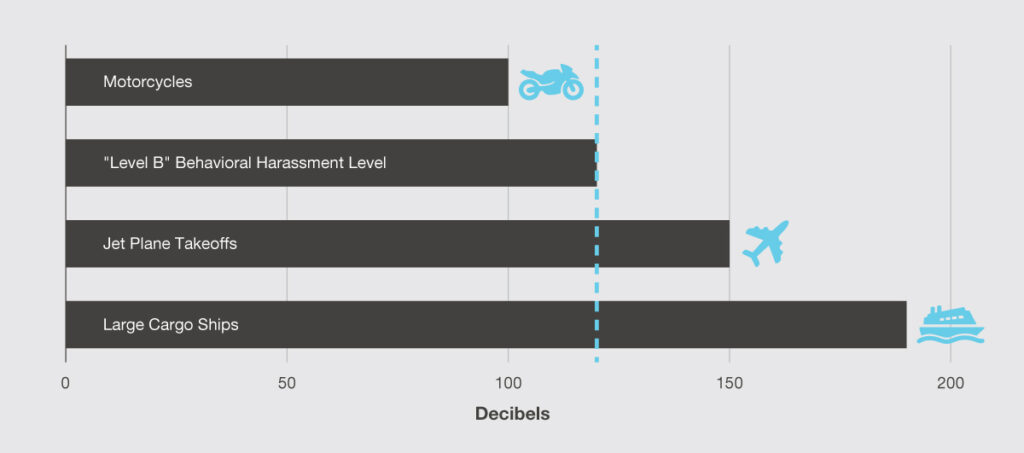

Increased shipping causes problems because sound does not travel underwater like in the air—it travels faster, for longer distances, and at louder volumes. For animals that rely on hearing more than sight, including orcas, loud noise is a constant irritant. The Marine Mammal Protection Act designates continuous noise near an orca at 120 decibels or more as “Level B” behavioral harassment, and violations can result in fines, jail time, or vessel forfeiture. For perspective, large cargo ships can emit up to about 190 decibels of noise, even louder than a plane taking off.

But if Southern Resident orcas swim in the same noisy waters as transient orcas, why is one group struggling while the other thrives? When I asked Rodell, the naturalist on my wildlife-watching tour, she agreed with other experts who have pointed out that it might come down to hunting methods.

“Transient orcas are hunting by stealth,” she explained. “They’re really not talking to each other because other marine mammals will hear them coming. Residents are much more chatty as they use their echolocation as a hunting tool.”

Increased shipping causes problems because sound does not travel underwater like in the air—it travels faster, for longer distances, and at louder volumes. For animals that rely on hearing more than sight, including orcas, loud noise is a constant irritant.

Orcas’ use of echolocation functions similarly to a submarine’s sonar. A killer whale sends out a series of clicks through the water. The clicks hit objects and bounce back to the orca as echoes, and the orca’s brain turns the echoes into a map of the water. Residents use this technique to find salmon from as far away as 500 feet but, in loud waters, may have difficulty distinguishing the echoes from shipping noise.

Taylor says that while an abundant supply of salmon is critical, it’s not the key factor affecting resident orcas today. Chinook salmon populations have risen and fallen over the past several decades, yet there was no similar rise and fall in Southern Resident populations during the same period. “My estimates show that while more salmon helps,” says Taylor, “the increase in salmon needed to offset the negative impacts of increased noise is just too large to be credible. Salmon stocks would have to rise to levels not seen in the last 50 or 60 years, and this is just not going to happen.”

Instead, Taylor’s initial research seems to indicate that increased shipping noise has directly contributed to a drop in the Southern Resident population. With the Southern Resident population peaking in 1995 and global shipping traffic growing since the 1990s, the data show that resident orca numbers have fallen as increased shipping has made the waters noisier over the past two decades.

While there is plenty of focus on dwindling salmon populations, not as much attention has been placed on solving the problem of marine noise pollution, leaving a path wide open for the development of innovative solutions. In a forthcoming report to be published by PERC, Taylor argues that there is a win-win option for both resident orcas and the shipping industry: a market for tradeable shipping-vessel noise pollution permits.

Seeing with Sonar

Orcas’ use of echolocation functions similarly to a submarine’s sonar. A killer whale sends out a series of clicks through the water. The clicks hit objects and bounce back to the orca as echoes, and the orca’s brain turns the echoes into a map of the water. Residents use this technique to find salmon from as far away as 500 feet but, in loud waters, may have difficulty distinguishing the echoes from shipping noise.

Quieting the Ocean

Under Taylor’s proposal, noise pollution permits would effectively establish an upper limit on allowable sound emitted from shipping vessels in the Salish Sea and function similarly to carbon cap-and-trade programs. Regulators would allocate a specific number of permits based on this limit. Part of establishing a permit program would be developing a structure to measure units of sound—something Taylor has spent years creating in rigorous detail. Large commercial ships create more noise than small boats, but even when it comes to large vessels, the type, design, and age of a ship’s technology significantly changes its noise emissions. Establishing a way of estimating sound output based on the size, speed, hull shape, ship load, and propulsion system is essential for an effective and functioning noise permit market.

Taylor recognizes that a system of noise permits might look similar to a tax on noise, but he notes a key difference. “With a pollution tax, the government sets the price, but the quantity bought is not under their control,” he says. “With the permit system, the government controls the number of permits issued but not their price.”

By placing a value on silence and allowing the market to innovate, we can maintain a thriving shipping industry while creating a quieter ocean for orcas.

Open and competitive auctions would allow individual market participants, not the government, to determine permit prices. Permits would also be tradeable. If one shipping company did not use all of its permits and another needed more, they could arrange a private transfer and set the price without government intervention. Making permit sales open to the public could also allow conservationists to buy permits and then hold rather than use them.

“The beauty of these systems,” Taylor says, “is that they incentivize shipping firms to choose quieter vessels, to perhaps lower speeds, alter ship length, switch out noisy ships for quieter ones, and investigate more thoroughly methods to reduce propeller cavitation”—the process that causes noise. “The basic idea is that firms and the private market are the best place to figure out how to reduce noise at the lowest cost. Imposing a speed limit or a rule saying you needed to have this or that technology will likely be inferior and more costly.”

Many of the solutions for marine noise pollution proposed by orca advocacy groups would require regulatory intervention and negatively impact the shipping industry. However, innovative research like Taylor’s shows that policymakers do not need to sacrifice commerce for conservation. Market-based solutions can reduce noise without unduly hampering shipping, and Taylor is collaborating with PERC to further explore the potential for noise permits to help conserve orcas.

Smoother Seas Ahead

A new Southern Resident calf was first spotted in mid-September, a rare and hopeful sight. As a new member of the so-called L-pod, the calf should be a cause for celebration. Yet, by late October, reports indicated that the young orca was emaciated and struggling to breathe, a stark reminder of the challenges that remain.

If nothing changes, Southern Resident numbers will continue to drop. The demise of Southern Resident orcas would be a tragedy for the wildlife tourism industry, animal lovers, and the Salish Sea’s natural and cultural heritage. Yet, there is a different path forward—one that aligns economic activity with conservation. By placing a value on silence and allowing the market to innovate, we can maintain a thriving shipping industry while creating a quieter ocean for orcas.