Summary

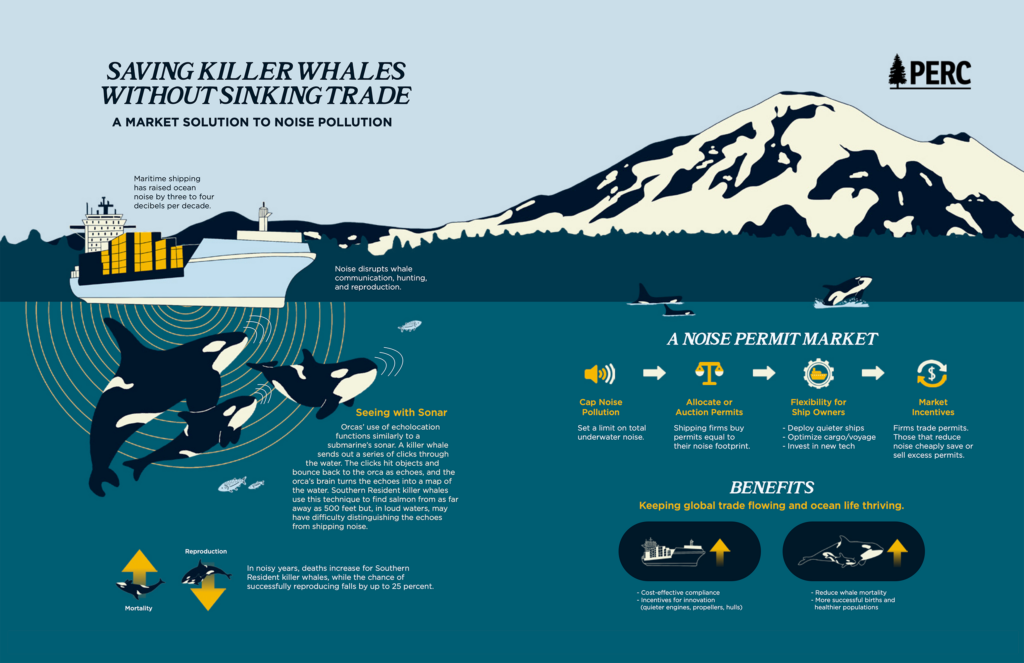

Maritime shipping is key to global trade, and international trade is key to prosperity worldwide. Despite generating enormous benefits, maritime shipping has raised the underwater ambient noise levels in the world’s oceans by three to four decibels per decade. This noisy trade has, until recently, had unknown impacts on the health of the world’s marine mammals. Drawing on a unique natural experiment, I link changes in the health of a killer whale population to changes in commercial vessel traffic in their critical habitat. Killer whale births are lower, and deaths higher, in noisy years compared to quiet ones—providing the first empirical evidence linking variation in noise from shipping to the health of a marine mammal population. But international trade need not be sacrificed to save the whales. Instead, I propose a market-based solution that prices underwater noise pollution that provides a win-win solution for both commerce and conservation. This approach offers a cost-effective alternative to traditional command-and-control policies and provides strong incentives for innovation and compliance.

Introduction

Maritime shipping is key to global trade, and international trade is key to prosperity worldwide. Today, approximately 80 percent of world trade by volume and over 60 percent by value is transported by ships. This trade brings new goods, technologies, and ideas from around the world and is critical to maintaining our standard of living and growing it into the future. Despite these benefits, shipping—like all economic activity—has environmental impacts.

Maritime shipping is responsible for perhaps 3 percent of global carbon emissions and a significant share of the world’s particulate and sulfur dioxide emissions. International organizations like the International Maritime Organization and regional governments like the E.U. have set new regulations and plans to reduce these impacts over the coming decades. There is, however, an impact of shipping on the environment that researchers have only recently recognized—underwater noise pollution—that may have deleterious effects on marine mammals.

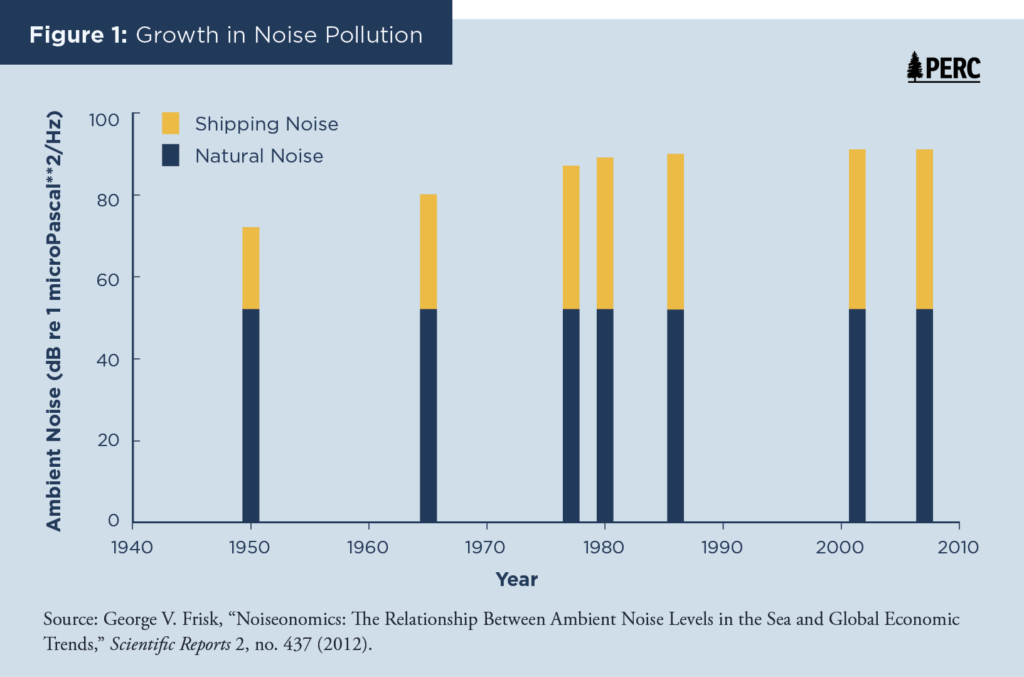

There is now widespread recognition that over the post-World War II period, maritime shipping has raised ambient noise levels in the world’s oceans. While estimates of the long-term change in ambient noise are somewhat speculative, one commonly cited source1George V. Frisk, “Noiseonomics: The Relationship Between Ambient Noise Levels in the Sea and Global Economic Trends,” Scientific Reports 2, no. 437 (2012). suggests ambient ocean noise has risen by three to four decibels (dB) per decade since the 1950s. This increase, tied to a simultaneous increase in maritime shipping, raised the ambient noise level in the low-frequency zone most relevant to marine mammals from approximately 72 dB in 1950 to more than 90 dB by 2007, as shown in Figure 1.

Not surprisingly, marine biologists and ecologists have started to study the impact of rising ambient noise levels on marine mammals. The reason is simple: Sound to marine mammals is much like sight is to humans—it is their primary sense for moving through the world around them. Low-frequency sounds (less than several hundred Hz) may be interfering with whale communication and social calls, whereas higher-frequency sounds (greater than several hundred Hz) potentially interfere with the echolocation employed to track prey. Therefore, the sounds emitted by maritime shipping may affect almost all aspects of whale life, making it more difficult to communicate, socialize, and hunt.

The idea that underwater shipping noise may adversely affect whales may seem somewhat incredible. It’s true that the global maritime fleet is large, containing over 100,000 commercial ships with more than 2.2 billion dead-weight tons of carrying capacity in 2021. Yet the world’s oceans are vast, covering over two-thirds of the globe. Noise interference seems unlikely. The problem, however, is that neither whales nor ships are spread evenly across the globe, and the same nutrient-rich coastal waters favored by whales are also home to many of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. Consequently, ship-to-whale interference is common. Whales cannot easily avoid vessel noise without abandoning prime feeding and calving grounds.

Despite these concerns, until recently researchers had made limited progress in understanding the connection between rising noise levels and changes in whale behavior. While many studies document changes in whale behavior when vessels are near, linking these behavioral changes to health outcomes for whales has been difficult. For example, although whales increase the amplitude of their calls when vessels are near, alter their travel paths, and change their hunting and socializing behavior, it remains an open question whether these changes are important to whale health or just minor inconveniences.

The Southern Resident Killer Whales

To study the impact of noise on whales, we need an almost impossible set of circumstances. We need to observe a rapid change in vessel traffic that drives changes in noise pollution; we need to ensure this noise pollution occurs in close proximity to a whale population; and we need detailed information on the health of this whale population both before and after the change in vessel traffic. Only then could we compare their health in a control period, when whales were relatively undisturbed, to their health in a treatment period, when noise was considerably higher. Fortunately, the Southern Resident killer whales off the Pacific Coast of Washington state and British Columbia provide us with just this trifecta of circumstances.

While today almost everyone knows something about killer whales, before the early 1960s, very little was known. Back then, killer whales were viewed as a pest to commercial fishing and a danger to humans. Not surprisingly, the whales were often shot and harassed by fishermen and boaters alike. Following the inadvertent capture of a live killer whale off the British Columbia coast in the early 1960s, the display and live capture industry was born. In response to the booming demand for display specimens and the lack of regulation prohibiting capture, both U.S. and Canadian authorities started to fund research studying killer whales. Soon after, killer whales were protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and then the Endangered Species Act. With protections starting in the 1970s, the Southern Resident population initially rebounded, but its numbers have fallen gradually for several decades.

As the Salish Sea population of killer whales has declined, government agencies and environmental groups have focused on the role that shipping vessels and their noise have on the mammals. In 2011, the National Marine Fisheries Service issued regulations prohibiting vessels from getting too close to killer whales.2NOAA Fisheries, “Regulations on Vessel Effects for Southern Resident Killer Whales,” accessed May 12, https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/west-coast/endangered-species-conservation/regulations-vessel-effects-southern-resident-killer-whales. It also considered, but did not adopt, establishing a “no-go zone” that would exclude vessels entirely from the western side of San Juan Island from May to September. Since then, the service has continued to analyze the impacts of vessel traffic and noise in evaluating whether to amend its current regulations.3NOAA Fisheries, “Southern Resident Killer Whale Noise and Disturbance Research,” accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/west-coast/science-data/southern-resident-killer-whale-noise-and-disturbance-research. Likewise, in recent years, some environmental groups have petitioned and sued the service to try to create a “whale protection zone” that would exclude vessels from certain areas and limit vessel speeds.4Orca Relief Citizens’ Alliance, Center for Biological Diversity, and Project SeaWolf, Petition to Establish a Whale Protection Zone for the Southern Resident Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) Distinct Population Segment under the Endangered Species Act and Marine Mammal Protection Act, November 2016; Center for Biological Diversity, “Trump Administration Sued for Failing to Protect Endangered West Coast Orcas,” August 19, 2019. Other groups have supported a voluntary program piloted in Washington that encourages large commercial vessels to reduce speeds in parts of Puget Sound and has been well-received by the shipping industry.5Quiet Sound, 2023–24 Quiet Sound Voluntary Vessel Slowdown Final Report (Seattle, WA: Quiet Sound, August 6, 2024), https://quietsound.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2023-24-Quiet-Sound-Slowdown-Final-Report_Aug6.pdf.

In contrast to top-down approaches such as exclusion zones or speed limits, a market in underwater noise pollution permits would provide flexibility to regulated vessels. It would also harness the powerful incentives firms face to innovate and improve efficiency. A permit market would leverage the reality that firms generally have the best and most complete information about how to reduce pollution—in this case, underwater noise emissions—most efficiently. It would also leave vessel operators with a host of options to figure out the best way to comply, whether by adjusting engine or propeller types, changing vessel size, replacing fleets, reducing speed, or otherwise.

The Southern Resident killer whales are perhaps the most studied whale population in the world, with detailed health and genealogical information on births and deaths accurately measured since the late 1970s. The Southern Residents spend most of their year in the Salish Sea, which contains the major international ports of Vancouver, Victoria, Seattle, and Tacoma, along with more than 20 other smaller ports. Lastly, with the growth in Asian trade generally and the explosive growth of China post-2000 in particular, the volume of vessel traffic in the Salish Sea has grown tremendously over the last 25 years. Figure 2 plots sightings and encounters with Southern Resident killer whales in the Salish Sea.

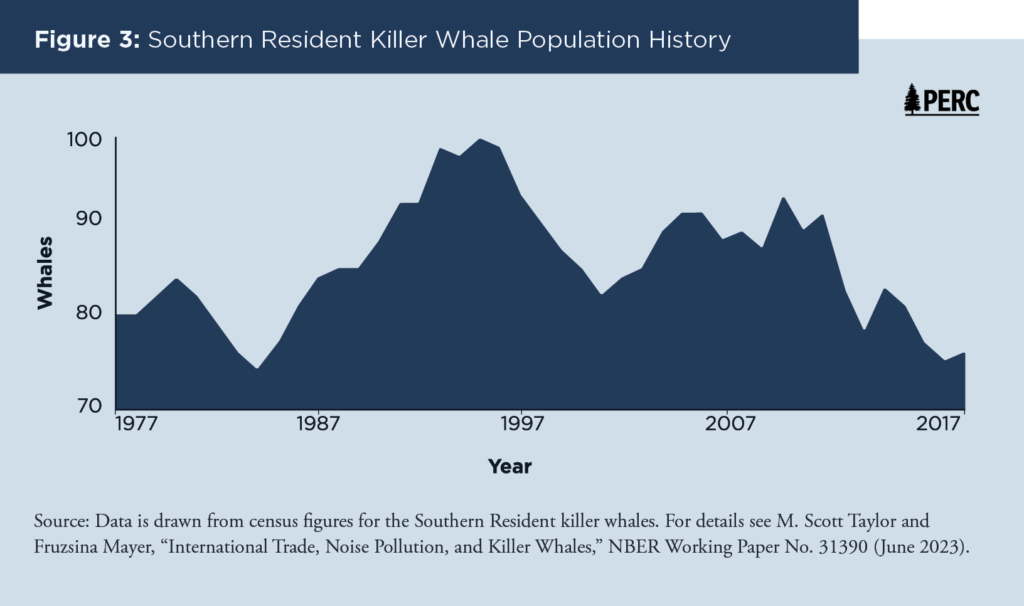

To understand why the last 25 years are so significant, in Figure 3 below, I plot the yearly population figures for the Southern Resident killer whales since the late 1970s. The population numbers are drawn from an official killer whale census that began in the early 1970s and continues to this day.

The figure reveals several important trends in the population over time. First, the population is subject to relatively large changes over just five-year periods. This saw-tooth pattern is thought to arise from swings in the availability of their favorite prey, Chinook, or king salmon. The Southern Resident population’s decline in the late 1990s, in particular, coincides with a large contemporaneous reduction in salmon availability. Post 2000, salmon abundance recovered, but killer whales did not. Instead, the whale population has declined over the last 25 years.

The initial pre-2000 growth period is easy to explain, since this is when killer whales were given legal protection that ended their harassment, capture, and killing. The post-2000 period remains a mystery, especially in light of the fact that the closely related Northern Resident killer whales have seen almost continuous growth in their numbers since their protection in the 1970s. This northern population grew from a mid-1970s population of just over 100 to more than 330 today. The critical difference between these two populations is their exposure to vessel noise. The Northern Resident killer whale’s habitat contains very few ports and no large international ports at all.

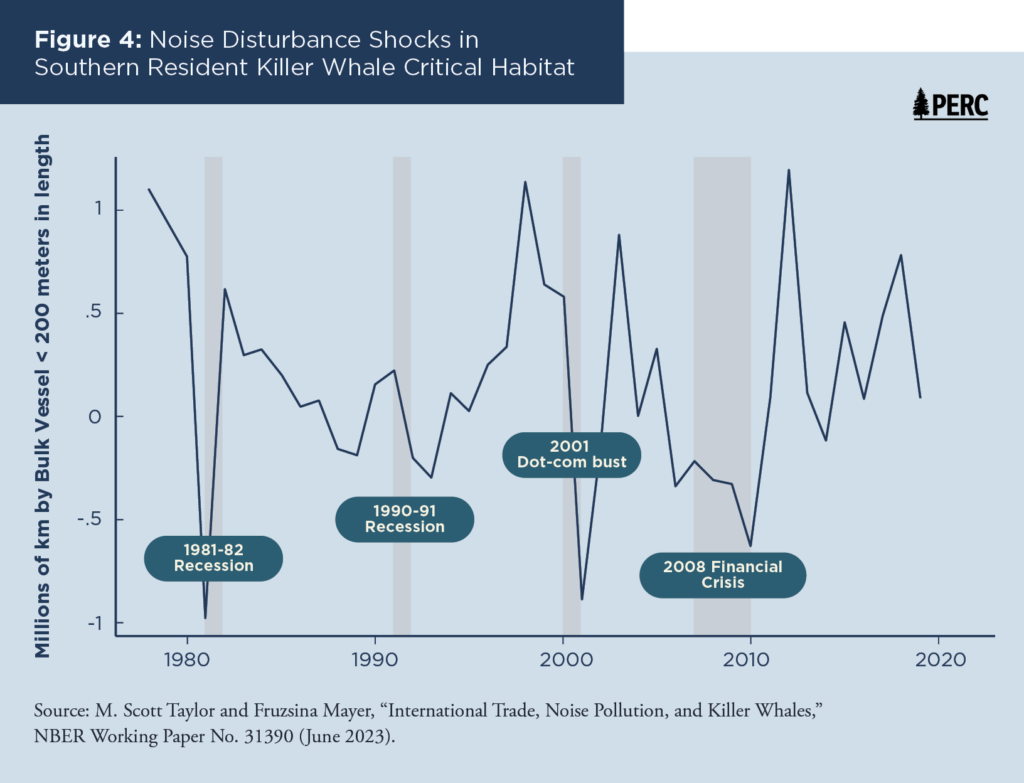

While this fact is suggestive, it is not convincing proof. To go further, we still need to link changes in noise exposure to changes in the health of the Southern Resident population. One way is to use variations in economic activity and shipping over time and relate these to changes in killer whale health. Since data on the Southern Residents is available from the late 1970s onward, numerous episodes of economic slowdowns and recoveries could provide just this variation. In Figure 4 below, I present a measure of the change in noise disturbance created by variations in commercial shipping in the Southern Resident killer whale critical habitat over the 1977-2019 period.

The measure of noise disturbance shown is an aggregate of the noise disturbances created by all types of large commercial vessels: tankers, container ships, bulk ships, and general and miscellaneous cargo. Each vessel class has activity in the critical habitat measured in kilometers traveled and then weighted by its relative contribution to noise disturbance. By weighting each vessel type, we end up with an aggregate measure of noise generated by commercial shipping. The changes in this measure over one year represent the shock or change in noise level shown in the figure.6We use changes because killer whales can, to some extent, avoid noisy shipping channels. Shocks to noise levels are unexpected surprises and better capture killer whale exposure to rising noise levels.

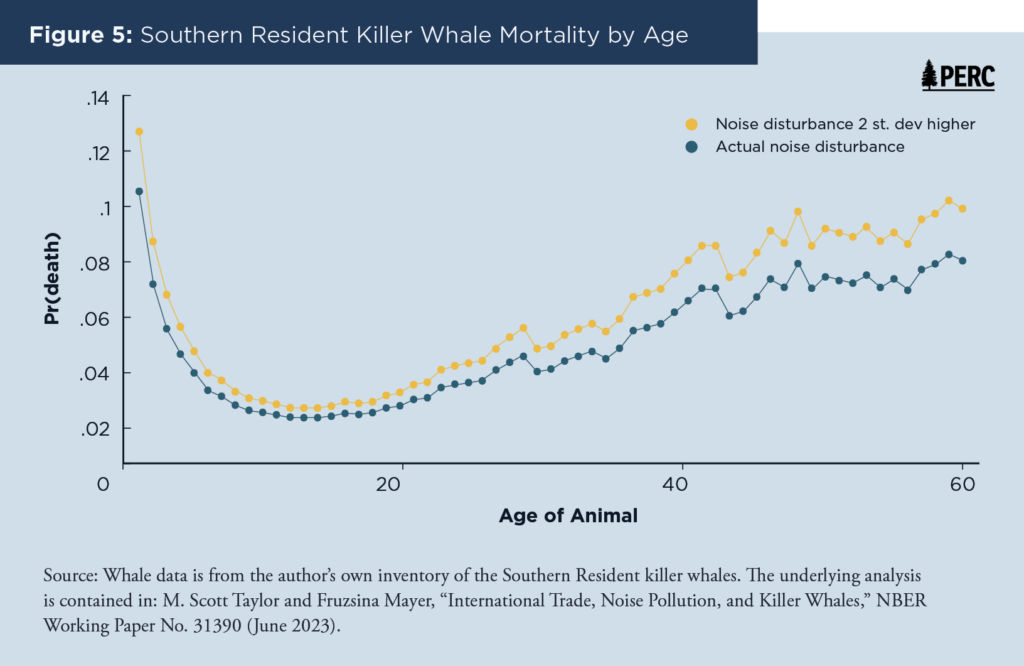

Using our measure of disturbance shocks, we can ask whether whales are healthier in quiet (negative shock) or noisy (positive shock) years. To measure killer whale health, we use the rich data from the existing whale census to estimate the probability of any whale dying in a given year, given its age, gender, and current prey availability. Controlling for these attributes, we then ask if this whale is more likely to die in a noisy year or quiet year. The answer is shown below in Figure 5.

The figure presents estimates of the probability of death for an average killer whale across its lifetime in two situations. Both lines show the probability of death is very high when young, then rapidly falls, and then rises again in later years. Also shown is the predicted probability of death in a noisy year when the noise disturbance is two standard deviations higher than usual. This is the yellow line, which is uniformly above the blue, showing that likelihood of death is considerably higher in noisy years. For example, at age 40, a Southern Resident killer whale is over 30 percent more likely to die in a noisy year.

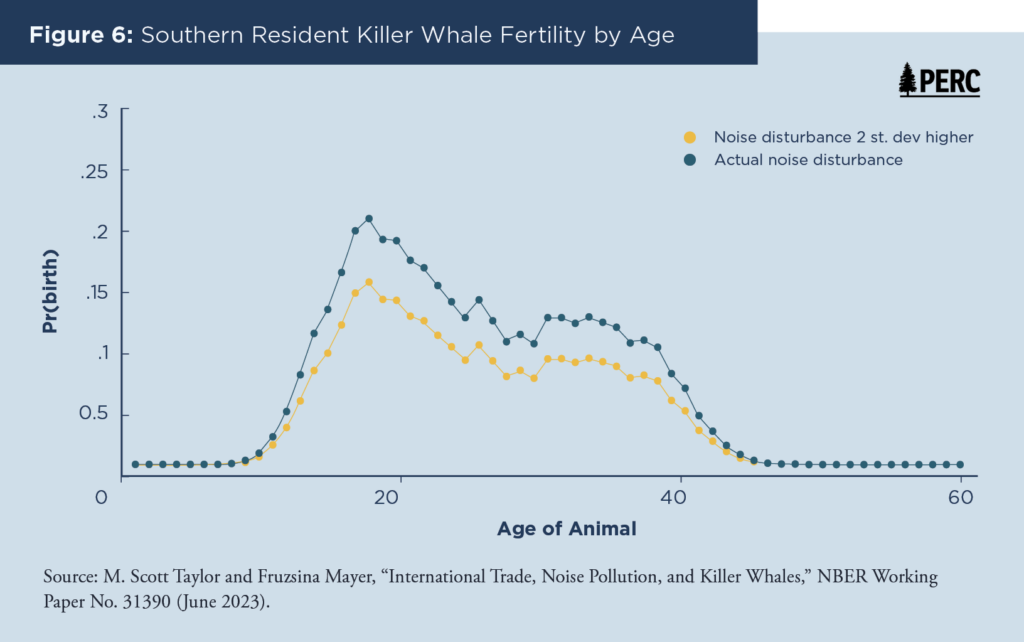

Turning to births, we can ask a similar question by examining female whales. Here we estimate the probability of a female Southern Resident killer whale giving birth in a given year by again controlling for its age, gender, and current prey availability. Since the gestation period for killer whales is 15-18 months, we now ask whether this female killer whale is more or less likely to give birth following a very noisy or quiet year—whether noise affects the likelihood of a successful conception and pregnancy. The answer is shown in Figure 6 below.

Turning to births, we can ask a similar question by examining female whales. Here we estimate the probability of a female Southern Resident killer whale giving birth in a given year by again controlling for its age, gender, and current prey availability. Since the gestation period for killer whales is 15-18 months, we now ask whether this female killer whale is more or less likely to give birth following a very noisy or quiet year—whether noise affects the likelihood of a successful conception and pregnancy. The answer is shown in Figure 6 below.

This figure presents estimates of the probability of a female killer whale giving birth at various ages. As shown, killer whales become fertile at around age 10 and enter a period of rapid senescence after age 40. In between these years, and perhaps especially in prime breeding years, the impact of noise is quite negative. In years of peak fertility, noisy years lower the probability of a subsequent successful birth by over 25 percent. These differences are smaller in some years, but the fertility patterns remain significantly different for most of their reproductive lifetime.

Putting these two findings together suggests vessel noise disturbance can have a considerable impact on the population of the Southern Resident killer whales. In noisy years, deaths increase, while conceptions and hence future births decrease. It is useful to put these impacts in context to think about how big they are. One way is to ask how important vessel noise is relative to salmon abundance. In terms of effects on killer whales, salmon abundance works in just the opposite way as noise does: It tends to raise births and forestall deaths. Therefore, salmon abundance is important, as previous researchers have also found. Unfortunately, our estimates show that offsetting the negative impact of rising noise in the killer whale critical habitat would require a permanent three standard deviation increase in salmon abundance. Such an increase would mean salmon abundance rebounding to levels not recorded in the 20th century. Therefore, restoring salmon stocks alone is unlikely to undo the impact of noise disturbance on killer whales.

An alternate way to evaluate these findings is to ask how large the killer whale population would have been if noise levels had remained at their pre-2000 average. Constructing this counterfactual requires a few more assumptions that are detailed in previous work (see Taylor and Mayer 2023).7M. Scott Taylor and Fruzsina Mayer, “International Trade, Noise Pollution, and Killer Whales,” NBER Working Paper No. 31390 (June 2023). This exercise provides the answer that the Southern Resident population would today be approximately 30 percent larger than current levels if noise pollution was kept at its pre-2000 levels. Such a change would largely undo the declines in their population since the late 1990s.

The differences we see in the mortality and fertility profiles, therefore, are economically and biologically significant. Increases in vessel noise have appreciably lowered births and raised deaths. The only question remains: What, if anything, should or could we do about it?

Pricing Noise Pollution

For economists, the solution to mitigate noise harmful to marine mammals is obvious, at least in theory. I have just described a situation where private firms inadvertently generate a noxious byproduct that, in sufficient quantity, damages a valuable asset. If these firms were manufacturing firms, the noxious substance was an airborne pollutant, and the valuable asset was human health, then the solution would be clear: put a price on the pollution. Without such a price, neither firms nor consumers bear the full cost of their activities.

In this case, the firms are vessel owners, the noxious substance is noise pollution, and the valuable asset is the health of the Southern Residents. Apart from relabeling, the economic logic remains the same: Firms could be incentivized to reduce pollution, with the strength of those incentives reflecting the costs and benefits of doing so. Good policy aims to strike the right balance, recognizing both the costs to firms of reducing pollution—what economists call abatement—and the benefits of a quieter environment. While valuing those environmental benefits is always challenging, and perhaps more so here than in other contexts, we can at least start by minimizing the costs of reducing noise. This is where market-based solutions shine.

Market-based solutions harness the powerful incentives firms already face to minimize costs and stay competitive. They recognize that firms—not regulators—usually have the best and most complete information about how to reduce pollution most efficiently. And they recognize that while “free markets” may have inadvertently created the problem, they can also be powerful tools in solving it—in this case by creating a new market in underwater noise pollution permits.

Turning theory into practice is never easy, but decades of experience with pollution markets have taught us a great deal about what works and what doesn’t.8There is a large literature discussing the lessons learned from past permit market introductions. See, for example, Robert N. Stavins, “Experience with Market-Based Environmental Policy Instruments,” in Handbook of Environmental Economics, ed. Karl-Göran Mäler and Jeffrey R. Vincent, vol. 1 (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2003), 355–435; Richard Schmalensee and Robert N. Stavins, “The Design of Environmental Markets: What Have We Learned from Experience with Cap and Trade?” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33, no. 4 (Winter 2017): 572–588; Meredith Fowlie and Nicholas Muller, “Market-Based Emissions Regulation When Damages Vary across Sources: What Are the Gains from Differentiation?” Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 6, no. 3 (May 2019): 593–632; and International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) and Partnership for Market Readiness (PMR), Emissions Trading in Practice: A Handbook on Design and Implementation, 2nd ed. (Berlin: ICAP; Washington, DC: PMR, 2021). The goal of a pollution permit market is to ensure that all market participants face the same incentives to reduce pollution, which is achieved via a common price per unit of pollution emitted, as determined by the market. When all participants face the same price for pollution emissions, they have the same incentive to alter their behavior to limit pollution. Firms will choose to find ways to reduce noise whenever doing so costs less than buying another permit.

Relatively cheap and easy abatement options would be employed first, while very expensive ones would not be chosen at all. Although all firms make these choices independently, every firm faces the same market for pollution emissions. This coordinates private incentives to ensure that the industry as a whole minimizes its costs of compliance. This cost-minimizing aspect of pollution permit markets is one of the key advantages of using a market-based system.

Another benefit of a market-based solution is that it encourages innovation. Firms are incentivized to invest in research and development to lower future compliance costs. With a price on noise pollution, the return to inventing a quieter engine or an advanced propeller system that decreases propeller cavitation is far larger. New vessels using such technologies would be rewarded with lower compliance costs, making such investments more attractive. Various options are currently available for quietening ships via changes in propeller systems. Low-cost options include simple propeller polishing; intermediate-cost options require retrofitting ducts or fins to improve water flow into propellers; larger and longer-term investments can bring improvements through new, skewed propellers, new hybrid propulsion systems, and computer-modelled improvements in hull design.9See, for example, the options outlined in Brandon L. Southall and Amy Scholik-Schlomer, Final Report of the NOAA International Symposium: Potential Application of Vessel-Quieting Technology on Large Commercial Vessels, 1–2 May 2007, Silver Spring, MD (Silver Spring, MD: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2008).

In contrast, most command-and-control regulations fail to minimize costs and provide few if any incentives for innovation. Indeed, they may even discourage it because regulations are often poorly targeted to the problem at hand. For example, a commonly proposed alternative policy to reduce ambient noise in the Salish Sea is to reduce vessel speed. While faster speed does raise noise levels, speed itself is not the problem—noise is the problem. By incorrectly targeting vessel speed, we would reduce noise levels but at potentially much higher costs. In contrast to a permit system, limits on speed provide no incentive for vessel owners to swap out older noisier vessels for newer quieter ones; limits on speed provide no incentives for vessel owners to optimize cargo across ship sizes to reduce noise emitted per value of cargo delivered; and limits on speed do not address the fact that some vessel types are simply far noisier than others. Requiring a large container ship and smaller bulk carrier to both reduce speed to 10 knots ignores the fact that at all speeds container ships are noisier than bulk carriers. As a result, command-and-control regulations can lower noise, but they will not do so at the least cost.

Unfortunately, these drawbacks of top-down approaches do not disappear with time. Slowing down the entire vessel fleet may imply less frequent port stops per vessel, requiring an even greater number of vessel arrivals to compensate. And slower vessels, while less noisy at any moment on their voyage, would spend more time in the Salish Sea, emitting noise over a longer period due to their extended time in the water.10One obvious benefit of a vessel slowdown policy is that vessels are less likely to strike whales, but strikes are not typically a problem for fast-moving predators. Vessel strikes are a serious problem for the less agile right whales common to the East Coast of North America, but they are not a first-order problem for the Southern Resident killer whale population.

Measuring Noise Pollution

To price noise pollution, we need a unit of account to measure it. In other settings, pollution is tracked using established units—tons of CO2 or sulfur dioxide, for example—but underwater noise pollution doesn’t have a standard unit, so we must construct a new one. Because vessel noise affects a specific volume of ocean over a certain period, the unit needs to reflect both space and time. One natural unit satisfying these criteria would be the number of hours a vessel disturbs one cubic kilometer within the Salish Sea.

Since a unit like cubic kilometers per hour (km3hr) is unwieldy, it helps to give it a more accessible name. With that in mind, I define a unit called the ”Balford” with units km3hrs, named in honor of Ken Balcomb and John Ford, two pioneers in killer whale research. For example, a vessel that disturbs one cubic kilometer of habitat for one hour has created 1 Balford of noise disturbance. Similarly, a vessel disturbing 0.5 km3 for 2 hours also has a measurement of 1 Balford. Therefore, Balfords are a unit of noise pollution that reflects both the scale (volume) and duration (time) of the disturbance.

Using data on the noise emitted by passing vessels, previous research has allowed us to estimate the average vessel disturbance, measured in Balfords, created by a variety of different vessels traveling at their average speeds.11All large commercial vessels are tracked by the Automatic Identification System, which provides extensive information via ship to ship, ship to shore, and ship to satellite transmission. This new definition of noise disturbance allows us to think of a vessel owner buying a certain number of Balfords in the pollution permit market to complete their planned voyage.12Implicit in the definition is a chosen noise threshold. The figures presented here assume that noise above 120 dB are disturbing to whales, and that noise dissipates spherically according to the inverse square law. For a detailed discussion of the noise disturbance model employed, see M. Scott Taylor and Fruzsina Mayer, “International Trade, Noise Pollution, and Killer Whales,” NBER Working Paper No. 31390 (June 2023). These purchases would be specific to the equipment operated and the distance traveled so that firms would know their compliance costs well in advance. With this unit in hand, we can now estimate how much noise different types of vessels generate—and how a permit system could be structured around it.

Pricing Noise Pollution in Practice

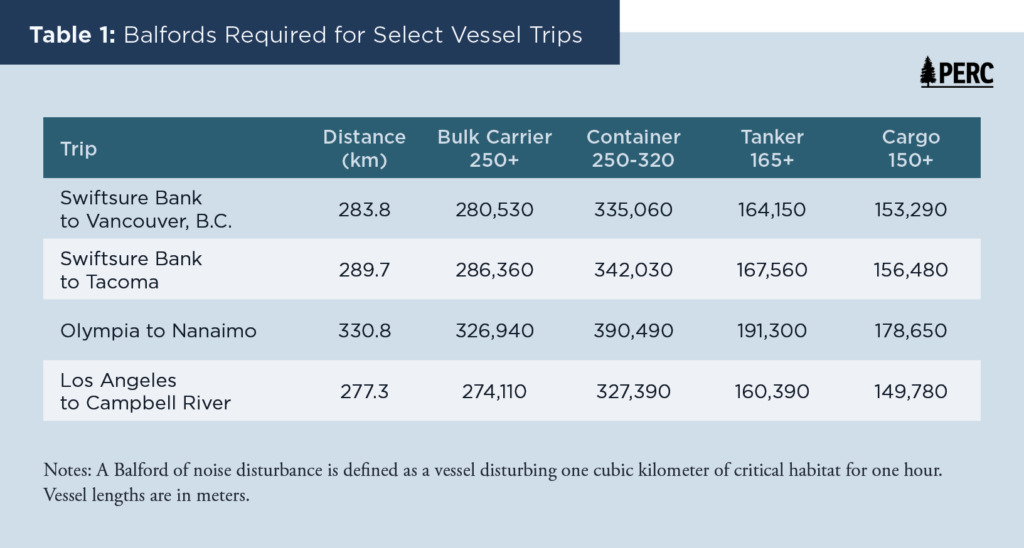

Table 1 offers a practical example of how pricing could work in practice, showing the noise costs of specific vessel trips through the Salish Sea. The destinations and equipment are specific, but the methods underlying the table’s construction can be used to price any planned voyage with virtually any vessel type. The table shows the Balfords required by different types of vessels making one-way trips between different ports in the Southern Resident killer whale critical habitat.

A large container vessel on a trip into the Salish Sea from Swiftsure Bank to Vancouver would require 335,060 Balfords for that one-way trip. Similarly, a trip within the Salish Sea from Olympia, Washington, to Nanaimo, British Columbia, made by a large tanker would require 191,300 Balfords. And a pass-through trip to Campbell River by a bulk vessel originating in Los Angeles would require 274,100 Balfords. Since the ship type, vintage, and planned average speed would be known, any shipping firm could estimate the number of Balfords needed for their particular journeys.

The price for emitting a Balford of disturbance could be set in a variety of ways. One approach is for a regulatory authority to cap the total allowable noise disturbance each year—effectively setting the supply of Balfords that could be sold to participants in the market. This is the method commonly used in the U.S. Acid Rain Program for SO2 emissions, for the European Union’s emission trading system for CO2 permits, for allowable catch permits in fisheries in both New Zealand and Norway, and in other settings. The benefit of setting a fixed and allowable limit on noise disturbance is that it ensures the whales are subject to a fixed level of disturbance.13A classic work in economics, Weitzman (1974), discusses the conditions under which we should prefer a system of noise pollution taxes over a system with a fixed noise pollution quota. With a noise pollution quota, any shift in the demand for shipping would be reflected in the price of permits but not in the amount of noise pollution emitted. Alternatively, with a given noise pollution tax, any shift in the demand for shipping would be felt in terms of the quantity of noise emitted in the Salish Sea rather than its price. One reason we might prefer a tradeable permit system with a fixed quota is if we believed the Southern Resident killer whale population was already very fragile so that increases in noise—which would be generated under a pollution tax system—could push them irreversibly toward extinction. Martin L. Weitzman, “Prices vs. Quantities,” The Review of Economic Studies 41, no. 4 (1974): 477–491. As more is learned about how lower noise levels affect whale health, the yearly cap could be adjusted. For example, an announced policy of gradually tightening the allowed number of permits over time would provide greater protection for the Southern Residents while giving firms time to adjust and reorganize their operations to meet future obligations.

Once the total number of Balfords is fixed, permits are sold or auctioned to the highest bidders, and the market determines their price through supply and demand. The price of each permit emerges from the market itself—based on how many permits are available and how much demand shipping firms have for them. Firms that need more permits to operate will be willing to pay more, while those with lower noise impacts or more flexibility may buy fewer or sell unused permits. This dynamic ensures the price reflects the value of reducing noise in the most cost-effective way.

Like any new market, a Balford permit system would introduce some uncertainty as firms adjust, especially in its early years. To ease this transition, common market design tools can be used. For example, allowing firms to bank unused permits for future use can reduce volatility and give them more flexibility. Price floors ensure that firms still have incentives to reduce noise, while price ceilings can limit unexpectedly high compliance costs. These features have worked well in other cap-and-trade programs and could help stabilize the market as it matures.

How Would Vessel Owners Adjust and Reorganize?

A key benefit of pricing noise pollution is that it allows firms to choose how to adjust their operations to minimize their compliance costs based on their specific routes and available vessels. While their flexibility may be limited in the short run, the set of potential adjustments grows significantly over time. For example, while trip destinations and many aspects of vessel class are largely fixed, within vessel-class adjustments could be made to larger or smaller vessels or perhaps to newer rather than older vessels on trips into the Salish Sea.

Because vessels vary in the noise they generate—based on factors like engine type, size, age, and speed—a market price for noise pollution would give vessel owners flexibility to reduce costs in multiple ways.14See, for example, the evidence and related work in: Scott Veirs, Val Veirs, and Jason D. Wood, “Ship Noise Extends to Frequencies Used for Echolocation by Endangered Killer Whales,” PeerJ 4 (2016): e1657. Even within a single ship class, such as container ships, firms could choose to deploy newer or quieter vessels on whale-sensitive routes. They might also adjust vessel size or travel speed, depending on what combination delivers the most cargo for the least noise. A pricing system gives firms the freedom to choose the most cost-effective strategy based on their own operations.

Some of these adjustments may be surprising to some. While large container ships are indeed the noisiest of vessels, they also carry much more cargo than smaller container ships. The largest post- and super post-Panamax container vessels, for example, carry up to 15,000 TEUs and exceed 320 meters in length.15Twenty-foot equivalent unit, abbreviated TEU, is a general unit of cargo capacity. The smallest container ships, up to 250 meters, are in the sub-Panamax category and carry between 2,000 and 3,000 TEUs. As a result, pricing noise pollution could encourage a shift toward fewer, larger container ships, because even though larger ships would pay higher compliance costs given their disturbance, the compliance costs per unit of cargo delivered may be smaller for larger ships.

Vessel age may be another important margin of adjustment. Newer vessels tend to be quieter than older vessels, in part due to improvements in propeller design, which also lowers destructive propeller cavitation. Firms could choose to allocate newer and quieter vessels to whale-sensitive routes, while keeping older vessels for others.

So far, efforts to reduce ship noise have been voluntary or temporary. As a result, there is limited information on the costs of noise abatement.16See Merchant (2019) for a review of current practices for reducing noise pollution from ships. In short, the vast majority of noise from ships comes from propeller movement, which creates shock waves. These waves are also destructive to the propeller itself; therefore, ongoing efforts to extend propeller life also tend to quiet ships. Nathan D. Merchant, “Underwater Noise Abatement: Economic Factors and Policy Options,” Environmental Science & Policy 92 (2019): 116–12. To the extent that these estimates do exist, they focus on individual ship-level adjustments in speed, equipment, and hull and propeller design. My own empirical research, connecting source-level noise to vessel characteristics, shows that vessel speed, age, dead-weight tons, and length all determine noise profile.17Noise levels vary greatly across vessels both within and across classes. As a result, recent estimates on vessels transiting Haro Strait suggest that 15 percent of the vessel fleet is responsible for 50 percent of the noise generated. This suggests that both within class and across class adjustments in the vessels transiting the Salish Sea could lower noise considerably. See Scott Veirs et al., “A Key to Quieter Seas: Half of Ship Noise Comes from 15% of the Fleet,” PeerJ Preprints 6:e26525v1 (2018). Many of these characteristics can be adjusted to reduce noise, although the benefits of slowdowns are small.

Of course, none of these adjustments are likely to be costless, especially in the short-to-medium term. Consequently, monitoring for compliance is important, although in this case it is relatively easy. Ocean-going vessels are not only very large; they are also tracked almost continuously by on-shore and satellite-based Automatic Identification Systems. All large vessels require these communications, and they ensure safe travel by identifying a vessel’s speed, heading, and many other characteristics. This information is sufficient to estimate a vessel’s noise pollution and the estimated cost of permits needed for its trip. These vessels are already tracked and are already subject to mandatory reporting to ensure compliance with a wide variety of other policies—be it customs operations, fuel restrictions, labor standards, or otherwise. Adding a provision for providing emission permits would be a relatively minor endeavor.18For anyone skeptical of the level of information we have on vessel movements, visit marinetraffic.com, and then navigate to the Salish Sea to investigate the types and locations of vessels currently in the area. Automatic Identification Systems provide us with vessel identifiers, and from these, vessel characteristics are relatively easy to find. There are many such vessel tracking companies using on-shore and satellite-based systems to provide real-time commercial information on vessel movements.

Setting a Target for Whale Recovery

While a market-based permit system can deliver a least-cost method for obtaining any amount of noise reduction, it does not tell us what the target level of emissions should be. It is clear that the noise pollution emitted in the Salish Sea is currently unsustainable for the Southern Residents, but how much noise reduction is needed to return this killer whale population to a path of growth and stability?

Returning the acoustic environment to what it was even 20 years ago would require a radical change in either shipping volumes or practices—both of which would be costly in the short run. A pragmatic solution would be to quantify the noise disturbance in a baseline year, using Balfords as the unit. Given this baseline, conservation policy could start by restricting next year’s disturbance to be no greater than that observed in the baseline. Further reductions would then incrementally and experimentally continue by moving to levels below the baseline in future years. Many cap-and-trade systems feature a gradual tightening over time with fewer and fewer allocations sold. The ultimate goal, however, is not a noise-free Salish Sea. The goal instead is to restore the acoustic environment of the sea in the most cost-effective manner possible, in the hope of stabilizing and perhaps even growing the Southern Resident killer whale population.

How far to restrict noise emissions depends on the program’s effectiveness, its compliance costs for firms, and the value society places on the Southern Residents. While it’s difficult to value killer whale populations, recent research offers insight.19For an introduction to valuation in contexts where non-use values are paramount, see: Daniel K. Lew, “Willingness to Pay for Threatened and Endangered Marine Species: A Review of the Literature and Prospects for Policy Use,” Frontiers in Marine Science 2 (2015): 96. In the United States, non-consumptive values may be used in designating critical habitat for species listed under the Endangered Species Act and in evaluating species recovery actions; in Canada non-consumptive values can be used in determining whether to list a species under the Species At Risk Act. One study develops estimates of both national and regional willingness to pay for marine species conservation using data drawn from a nationwide survey of over 5,000 U.S. households for eight threatened or endangered marine species.20Daniel K. Lew and Kristy Wallmo, “A Comparison of Regional and National Values for Recovering Threatened and Endangered Marine Species in the United States,” Journal of Environmental Management 170 (2016): 65–75. Using choice experiment methods, it estimates that, on average, U.S. households are willing to pay approximately $110 per year (in 2023 dollars) for 10 years to help the Southern Resident killer whales reach full recovery. A smaller figure of approximately $60 per year (in 2023 dollars) for 10 years was estimated for the more limited conservation goal of improving the Southern Resident population from endangered to threatened.

These figures seem large at first blush—there are over 130 million households in the United States—but less surprising when we consider the popularity of Sea World, Shamu, and the associated killer whale shows that have run since the mid-1960s. Killer whale awareness was also primed by “Free Willy,” the incredibly popular 1993 major motion picture about freeing one such captive whale. (“Free Willy” made $320 million in 2023 terms and had three sequels.) This interest has, if anything, grown over time as demonstrated by the Southern Resident’s Facebook page, an active Orca Network of volunteers, press stories about large sums of money spent on public efforts to free two remaining captive whales (Keiko and Lolita) and return them to their natural habitat. And in many ways, the Southern Resident killer whales are probably the most visible and highly valued whale population on the planet.

Conclusion

International trade is a key driving force for prosperity worldwide, and maritime shipping is the most important transportation mode for many of the world’s goods. It is especially important for exports from developing countries, whose citizens are relying on international trade to transform their economies. At the same time, killer whales are keystone species at the top of the food chain and important components of ocean biodiversity. Removing keystone species can create severe and costly unintended consequences for human populations.21For examples, see: Eyal Frank and Anant Sudarshan, “The Social Costs of Keystone Species Collapse: Evidence from the Decline of Vultures in India,” American Economic Review 114, no. 10 (2024): 3007–40; and Jennifer L. Raynor, Corbett A. Grainger, and Dominic P. Parker, “Wolves Make Roadways Safer, Generating Large Economic Returns to Predator Conservation,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 22 (2021): e2023251118.

In many cases, incentives to reduce noise pollution would align with those in the shipbuilding industry, where engineering efforts to lessen propeller cavitation improve fuel efficiency and propeller life while reducing propeller noise. Indeed, the scope for win-win solutions is larger still. Port authorities could direct the revenues raised by noise pollution pricing to fund salmon hatchery efforts or stream restoration, which could further enhance orca recovery. Moreover, directing permit market revenues to these ends may go some way in lessening the contentious and often costly legal battles port authorities have with environmental groups over the impacts of port upgrades or expansions.

Killer whales are majestic creatures with complex social structures and high intelligence. It seems incredible that we would jeopardize their existence today after forestalling their extinction last century. But economics, and good economic policy, are not about absolutes: We don’t need to shut down international trade to save the whales. Good policymaking is about making efficient trade-offs. In the whaling case, we cannot shut down major ports, divert ships hundreds of kilometers from their routes, or ban certain vessel classes. The costs of doing so would be astronomical. We can, however, make adjustments at the margin by giving ship owners an incentive to reduce vessel noise.

By pricing vessel noise, we can align conservation with commerce—protecting one of the ocean’s most iconic species without sacrificing the global flow of goods. It’s not a choice between whales and trade, but a smarter way to manage both.