Introduction

It’s springtime in western Wyoming, and a mule deer is on the move. She’s walking slowly but steadily, heavily pregnant with twins and hungrily browsing on new green shoots along the way. With other members of her herd, she sets out across an undulating sea of sagebrush, skirting the western side of the Wind River Mountains toward her higher-elevation summer range on the border of Grand Teton National Park. Over the next few weeks, she and roughly 5,000 other deer that use all or part of this “Red Desert to Hoback” migration route will traverse public and private land, livestock operations, and housing developments, dash across roadways, then disperse to fawn and forage. When temperatures drop and the snow starts to fly in the fall, they’ll reverse course back down to their winter range, where conditions are milder.

Some, like the legendary Deer 255, GPS-collared by the Wyoming Migration Initiative, will travel more than 200 miles, during which she may have to navigate fences more than 170 times. And each crossing is a gamble—one study conducted in areas of Colorado and Utah found that each year, a deer, elk, or pronghorn dies for every 2.5 miles of wire fence, mostly by becoming entangled in the top two wires.1Harrington, J.L. and Conover, M.R., 2006. Characteristics of ungulate behavior and mortality associated with wire fences. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 34(5), pp.1295-1305. And while the rate of death likely varies, what’s clear is that with at least 620,000 miles of fencing in the western United States,2McInturff, A., Xu, W., Wilkinson, C.E., Dejid, N. and Brashares, J.S., 2020. Fence ecology: Frameworks for understanding the ecological effects of fences. BioScience, 70(11), pp.971-985. failed fence crossings kill a lot of ungulates. What’s more, 40 percent of crossings were found to affect mule deer and pronghorn behavior in some way,3Xu, W., Dejid, N., Herrmann, V., Sawyer, H. and Middleton, A.D., 2021. Barrier Behaviour Analysis (BaBA) reveals extensive effects of fencing on wide‐ranging ungulates. Journal of Applied Ecology, 58(4), pp.690-698. which carries an energy cost.

Migratory deer like these, along with elk and pronghorn, are a part of the lifeblood of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, a central link in the long food chain that depends on this seasonal “pulse” of moving animals. But Yellowstone’s migratory heartbeat is faltering: Wide-ranging wildlife are under pressure here, and around the world, like never before due to growing numbers of human-built barriers to movement. And major wildlife conflict can arise when large herbivores like elk break fences. Conservation groups are raising the alarm, but new blockages accumulate faster than they can be dismantled, slowing and stopping migrations like plaque in ecosystem arteries.4Kauffman, M.J., Cagnacci, F., Chamaillé-Jammes, S., Hebblewhite, M., Hopcraft, J.G.C., Merkle, J.A., Mueller, T., Mysterud, A., Peters, W., Roettger, C. and Steingisser, A., 2021. Mapping out a future for ungulate migrations. Science, 372(6542), pp.566-569.

Virtual fencing, an emerging technology, is offering an alternative to this picture in places like the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Imagine a brighter future for our mule deer beginning her Red Desert trek. Unlike today, when migratory deer have to cross hundreds of physical fences annually, halting or shifting their migratory behavior,5Xu, W., Dejid, N., Herrmann, V., Sawyer, H. and Middleton, A.D., 2021. Barrier Behaviour Analysis (BaBA) reveals extensive effects of fencing on wide‐ranging ungulates. Journal of Applied Ecology, 58(4), pp.690-698. these deer in the future move more freely across the landscape. That’s because thousands of miles of aging physical fencing, once the only tool for containing livestock and delineating property boundaries, have been removed, replaced by virtual fences that can manage livestock but are invisible to wildlife. Our deer and her migratory herd navigate smoothly through pastures, fields, and forests. Glossy, healthy cattle watch them pass, then go back to grazing on newly-sprouted forage that ranchers detect and herd them toward from their laptops or phones. The nearby creek is cattle-free, running clean and cold and thickly fringed by willows and cottonwood, with baby trout finning through the dappled shade below.

In this same future scenario, ranchers face lower costs of fence maintenance, with fewer miles of physical fence to maintain and less elk damage to fences. And perhaps rancher costs from carnivore conflict are down as well, thanks to virtual fences. As grizzly bears and wolves continue to expand their range, virtual fencing collars could enable ranchers to move cattle away from conflict risk or keep them from grazing around tall larkspur—a plant that is often fatal to cattle—reducing carcasses on the landscape and their “dinner bell” effect on hungry carnivores.6Wells, S.L., 2017. Livestock depredation by grizzly bears on Forest Service grazing allotments in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (Doctoral dissertation, Thesis, Montana State University, Bozeman, USA). Meanwhile, the nearby community of Pinedale is seeing growing revenue from wildlife tourism thanks to healthy wildlife populations and wide-open scenery, while a new generation of ranchers is recording record profits as forage-use efficiency increases and lost cows are quickly recovered.

Connected, wildlife-friendly landscapes as imagined here, where agricultural livelihoods and recreation are better supported even as wildlife conflict is also reduced, are possible. Virtual fencing can help bring about this future and is now technologically mature enough for its conservation potential to be realized. And while virtual fencing is not the only tool needed to make such progress, it can unlock major components of this conservation vision in landscapes far beyond the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Conservationists may recognize the benefits of the technology, yet virtual fencing must first and foremost address the agricultural and economic needs of the producers who use it. This technology is not a one-way street, but instead an opportunity for conservationists to show, not tell, ranchers that they care about agricultural viability and keeping livestock on the landscape.

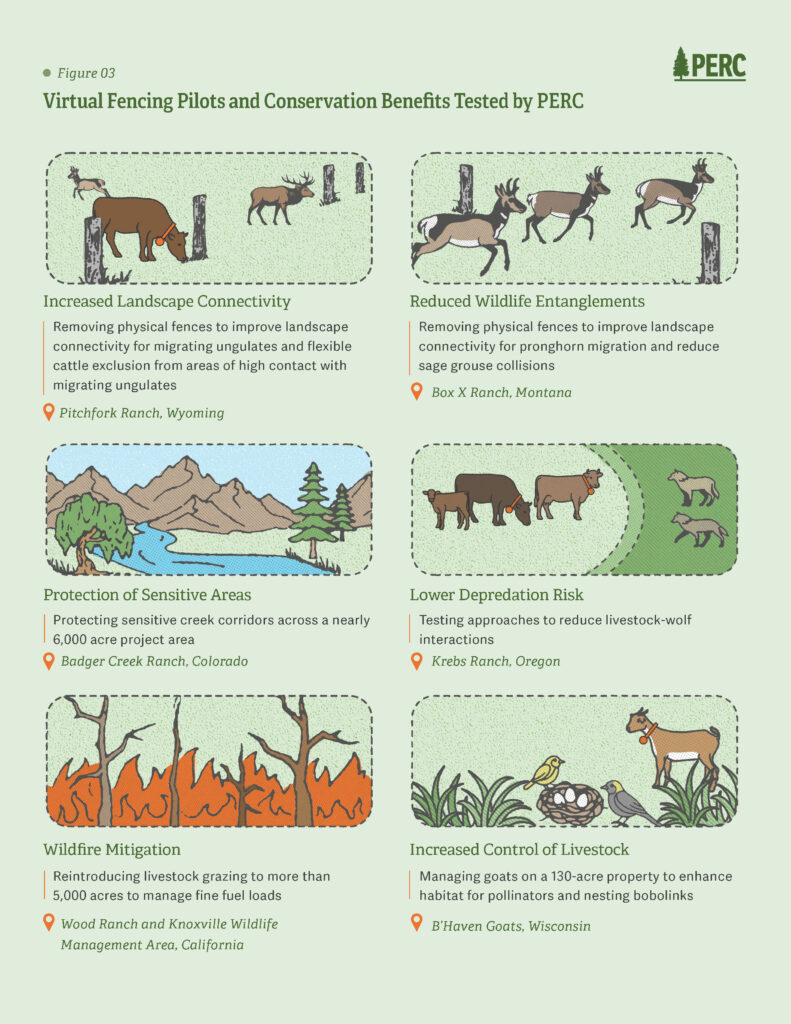

This report highlights the conservation potential of virtual fencing,7Jachowski, D.S., Slotow, R. and Millspaugh, J.J., 2014. Good virtual fences make good neighbors: opportunities for conservation. Animal Conservation, 17(3), pp.187-196. and invites the conservation community to consider more broadly the technology as a tool to conserve landscapes. Over the past several years, PERC and many other conservation groups have begun investing in and learning about virtual fencing’s conservation utility through pilot projects on working ranches and an in-depth 2024 workshop, which brought together key players from agriculture, conservation, technology, and government to discuss the future of the technology. The time is now ripe for conservation groups, agencies, and others interested in conservation outcomes in rangelands to help realize the potential of virtual fencing. This report presents current conservation benefits of virtual fencing, and explores two potential future benefits that could be created. It also provides an overview of potential contract structures and monitoring approaches.

Underpinning all of this conservation potential is the reality that large landscape conservation in rangelands depends on keeping working lands working, for livestock producers and wildlife. The alternative to working rangelands is generally not more conservation, it is less, through conversion into housing and other land-uses less compatible with conservation. That’s why we see so much potential in virtual fencing: It can increase conservation value while keeping livestock operations functional. To that end, virtual fencing must work for producers, make sense for their bottom lines, and become widely adopted before it can become a conservation tool at scale. This report, in an effort to achieve those goals, examines the barriers to rancher adoption at scale, alongside strategic actions conservationists can take to dismantle them.

Recommendations for Conservation Organizations

1. Leverage current virtual fencing functions to benefit conservation:

- Substitute for physical fences to improve connectivity.

- Concentrate and precisely locate livestock to enhance habitat and reduce wildlife conflict.

- Time livestock rotations to improve habitat and reduce wildlife conflict.

- Exclude livestock from sensitive areas to minimize grazing impacts.

2. Grow future conservation applications of virtual fencing:

- Improve administration and impact of conservation grazing programs.

- Reward “conservation mode” within software platforms.

3. Help dismantle economic, social, and efficacy barriers to adoption:

- Expand extension education and communities of practice.

- Innovate, pilot, and scale conservation finance and incentives.

- Fund and facilitate research to discover new functions and benefits.

- Foster policy change to increase adoption.

Note: The current virtual fence functions for conservation were developed by Bennett et al. in their article Advancing Conservation Through Virtual Livestock Fencing, currently in review.

How Virtual Fencing Works

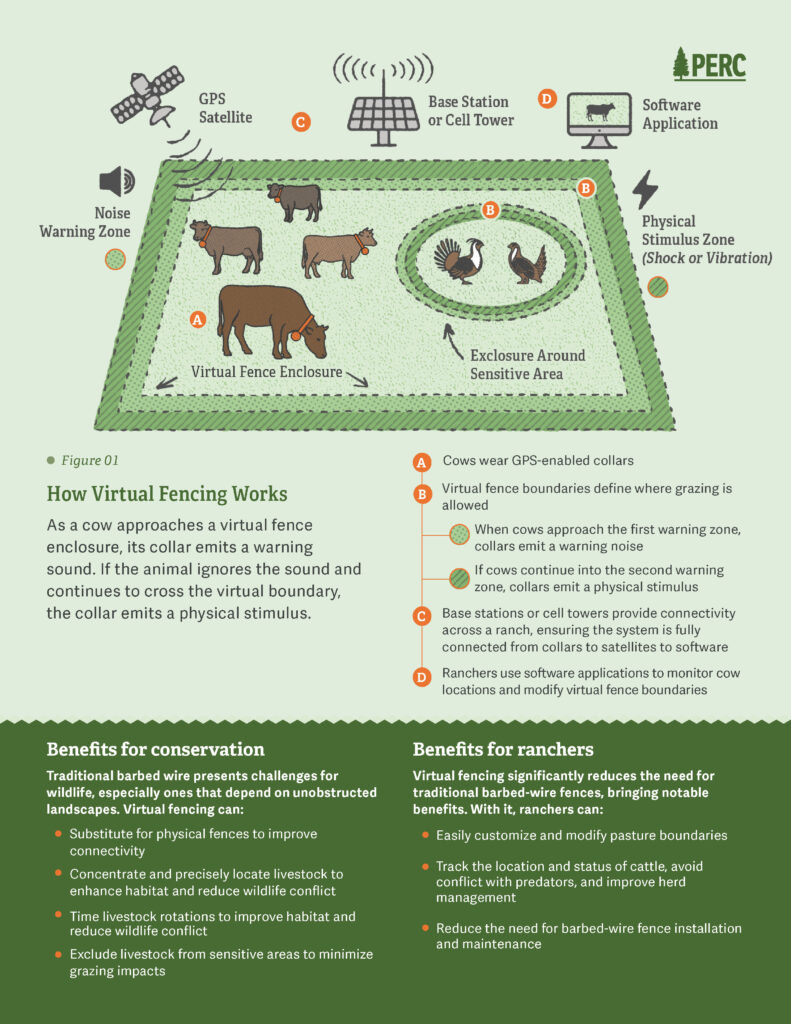

Virtual fencing has been under development for decades and has taken off over the last decade in the ranching world.8de Avila, H.A., Launchbaugh, K.L., Ehlert, K.A. and Brennan, J.R., 2025. Virtual fence: New realities beyond barbed wire. Rangelands, 47(1), pp.3-8. But its potential as a conservation tool is only starting to be widely recognized. Virtual fencing works by enforcing digital boundaries (the virtual fence) that can replace physical fencing on a landscape, using GPS collars that digitally “herd” livestock via sound and mild physical stimulus.9It is worth note that what we describe here is a general overview of the functionality of a virtual fencing system. There are several manufacturers of virtual fencing technology and each of their respective systems contain additional nuance. The standard design has relied on radio frequency towers, or base stations, that transmit collar locations to a digital platform via satellites, although some collar designs can function using cellular networks alone. The animals’ locations are precisely tracked and automatically compared to the virtual fencing boundaries, and warning sounds are delivered to the collared animals only if the boundaries are approached or breached, backed by a physical stimulus if the sound is ignored.10Antaya, A., Dalke, A., Mayer, B., Noelle, S., Beard, J., Blum, B., Ruyle, G. and Lien, A., 2024. What is virtual fence? Basics of a virtual fencing system. University of Arizona Extension. Recently, manufacturers have begun substituting vibrations as the physical stimulus instead of electrical shocks. On the digital platform, each collared animal can be tracked remotely, and digital boundaries can be moved, with the feedback from the collars helping the animals adjust to the new boundaries.

A key part of what makes virtual fencing effective and humane is the training period, when animals learn that the sound is a warning of an impending physical stimulus, and quickly learn to respond to the sound alone. Initial questions about animal welfare have been largely resolved; stress responses of livestock to the collars are low and comparable to those of physical fences,11Wilms, L., Komainda, M., Hamidi, D., Riesch, F., Horn, J. and Isselstein, J., 2024. How do grazing beef and dairy cattle respond to virtual fences? A review. Journal of Animal Science, 102, p.skae108. and precision training schedules during the initial training period mean that animals rarely experience physical stimuli. In rugged terrain and closed-canopy environments, however, GPS errors can lower effectiveness and potentially increase animal welfare concerns, making virtual fencing boundary selection a key component of success.12Versluijs, E., Tofastrud, M., Hessle, A., Serrouya, R., Scasta, D., Wabakken, P. and Zimmermann, B., 2024. Virtual fencing in remote boreal forests: performance of commercially available GPS collars for free-ranging cattle. Animal Biotelemetry, 12(1), p.33.

This basic virtual fencing design continues to evolve and improve: Collar design changes have increased retention and ease of maintenance (e.g., solar-powered collars), new tower designs are much cheaper and more portable than they used to be, and the technology continues to evolve in myriad ways. Warning sound applications are also improving, with directional left/right differences in volume letting animals “hear” which side the virtual fence is on, similar to how livestock orient within herds.13Halter, 2026. Virtual fencing for cattle: complete guide for ranchers. Available at: https://www.halterhq.com/en-us/articles/virtual-fencing-for-cattle. Accessed 1/10/2026. Cutting-edge analytics of changes in movement behavior recorded by collars are also showing promise for detection of sickness, predator interactions, injury, and reproductive phase. At the same time, applied rangeland research into virtual fencing effectiveness has blossomed,14Special issue of Rangelands, 2025. yielding excellent resources to help ranchers understand virtual fencing technology and its opportunities and constraints,15May, T.M., Burnidge, W.S., Vorster, A.G., Dalke, A.M., Aljoe, H., Lien, A.M. and Noelle, S.M., 2025. Is virtual fencing right for you? Producer considerations for successfully deploying and managing livestock with a virtual fence system. Rangelands, 47(1), pp.9-15. which are now widely available online, from podcasts and written materials, and through extension and peer-to-peer learning opportunities.

Although widely adopted in ranching, virtual fencing is only beginning to be recognized for its potential to resahape conservation across working landscapes.

Compared to physical fences, virtual fencing is still nascent across ranching landscapes in the U.S. This is partly because adoption of this relatively new technology is still propagating within the ranching community, although there are geographic pockets of very high adoption. Virtual fencing is perceived by some producers as unproven or risky compared to physical fencing, although as adoption increases and evidence of success spreads, this will likely change. The high costs of installing and maintaining physical fencing, combined with external factors such as wildfires that destroy physical fences or cost shares and other financial compensation approaches that reduce the cost of virtual fencing to ranchers, can make virtual fence adoption more appealing.16Harris, Tyler J. 2025. What influences rancher adoption of virtual fence? Masters of Science Thesis. University of Oregon. Still, expanding virtual fencing uptake beyond the “early adopter” group most willing to try new tools and technologies to less risk-tolerant parts of the ranching community will take time, effort, and innovative approaches to address cost and other adoption barriers.

Even as adoption increases, physical fences will likely remain an important tool for managing livestock and wildlife alike.17Smith, D., King, R. and Allen, B.L., 2020. Impacts of exclusion fencing on target and non‐target fauna: a global review. Biological Reviews, 95(6), pp.1590-1606. Physical fences are often required by state law to demarcate ownership boundaries and prevent wandering livestock and humans from damaging neighbors’ property.18Rumley, R. W. 2021. States’ “Fence Law” statutes. National Agricultural Law Center. Available at: https://nationalaglawcenter.org/state-compilations/fence-laws/. Accessed 1/10/2026. Indeed, many practices will focus on replacing interior fences where feasible while leaving boundary fences intact. Fences can reduce wildlife conflict and may be necessary to prevent wildlife from accessing attractants.19Walter, W.D., Lavelle, M.J., Fischer, J.W., Johnson, T.L., Hygnstrom, S.E. and VerCauteren, K.C., 2010. Management of damage by elk (Cervus elaphus) in North America: a review. Wildlife Research, 37(8), pp.630-646. They exclude elk and other large herbivores from haystacks; bears from beehives, orchards, and poultry yards; and large carnivores from boneyards and calving/lambing pastures across the United States and beyond. Similarly, excluding livestock and wildlife from roads will also likely involve physical fencing for the foreseeable future, given the proven efficacy of hard fencing in decreasing collisions and increasing connectivity for wildlife, in combination with well-designed wildlife crossing structures.20Denneboom, D., Bar-Massada, A. and Shwartz, A., 2021. Factors affecting usage of crossing structures by wildlife–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 777, p.146061. Physical fencing is also an important conservation tool for containing invasive and reintroduced animal species.21Watt, D., Whittington, J. and Heuer, K., 2025. A follow‐up assessment of wildlife‐permeable fences used in the reintroduction of bison. Wildlife Biology, 2025(3), p.e01171. Overall, adoption and success of virtual fencing will rely on rancher trust and interest in the outcomes the technology can create.

What Conservation Opportunities Does Virtual Fencing Unlock?

Conservation practitioners are beginning to use virtual fencing as a tool, and are attracting widespread interest among the research community as its potential becomes clearer. While much is left to be learned, conservationists and ranching partners are demonstrating ecological benefits and piloting new approaches.

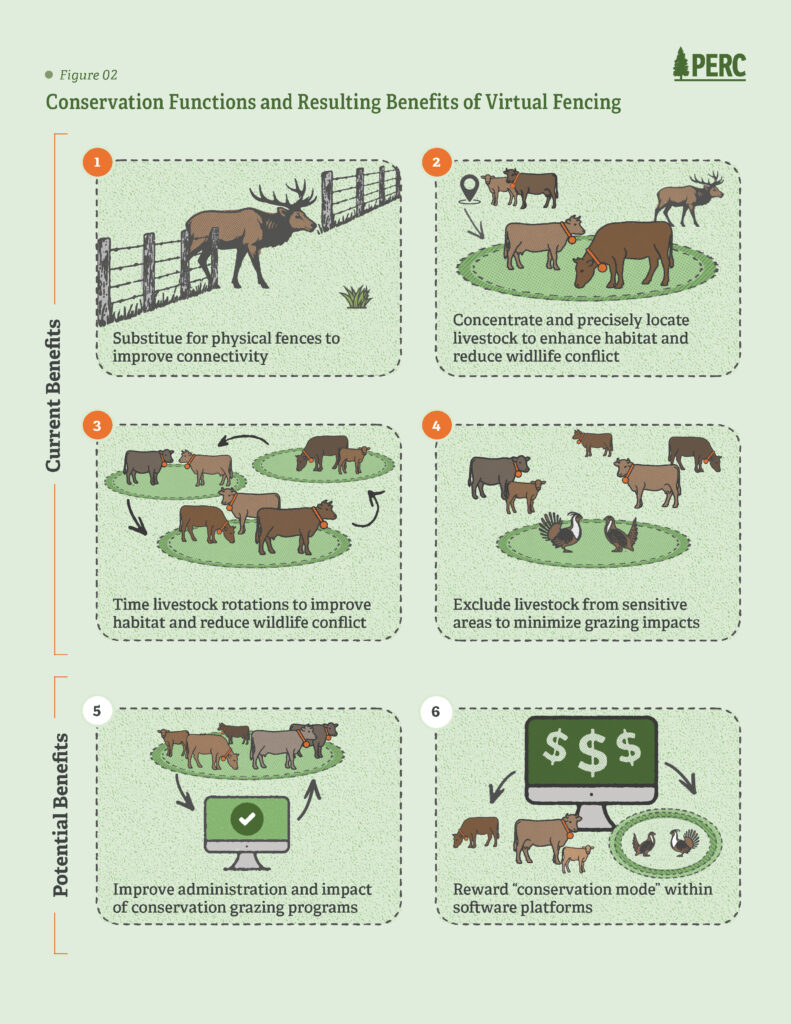

Currently, there are four primary conservation functions that can be created by virtual fencing:22Bennett, D.E., Brammer, T., Merkle, J. A., Smith, K., Regan, S., Stoellinger, T., Middleton, A., Barker, K., Hochard, J. P., Lendrum, P. E., Welty, E., Benjamin, C., Yablonski, B., 2025. Advancing Conservation Through Virtual Livestock Fencing (under review: Biological Conservation).

- Substitute for physical fences to improve connectivity.

- Concentrate and precisely locate livestock to enhance habitat and reduce wildlife conflict.

- Time livestock rotations to improve habitat and reduce wildlife conflict.

- Exclude livestock from sensitive areas to minimize grazing impacts.

We also identify two additional conservation functions that could be provided using virtual fencing in the future:

- Improve administration and impact of conservation grazing programs.

- Reward “conservation mode” within software platforms.

Current Primary Conservation Functions and Benefits

A growing body of evidence is pointing toward virtual fencing as a conservation tool that can deliver four primary conservation functions, along with many resulting benefits.

1. Substitute for physical fences to improve connectivity

Reduced need for physical fences could greatly increase landscape connectivity for wildlife. Fences are a growing problem for wildlife in the United States and beyond, and virtual fencing could not only slow their rampant growth but also restore connectivity across landscapes through the removal of existing physical fences. Additionally, virtual fencing could prevent the construction of new physical fences. For example, as housing demand drives increased subdivision of working rangelands, instead of using hard fences to delineate housing from pastures, virtual fencing could be used instead. Likewise, existing fencing across much of the western U.S. is aging, and these older fences pose a greater risk to wildlife from entanglement in loose wires. Virtual fencing could reduce the need for new physical fences and provide a substitute for dilapidated existing fences in need of replacement. Given that fences, including virtual fencing, are key operational infrastructure for farms and ranches, it should also be compatible with legal requirements of conservation easements that allow for agricultural improvements. However, when land impacted by virtual fencing is conserved with an easement, the producer should ensure compatibility with the terms and consult with the land trust. Importantly, virtual fencing will allow for the reduced reliance on hard fences without reducing the ability of livestock producers to manage their herds, supporting financial viability for families in rural communities.

2. Concentrate and precisely locate livestock to enhance habitat and reduce wildlife conflict

Concentrating and precisely locating livestock also holds great conservation promise. Precise, concentrated grazing using virtual fencing can reduce invasive plant species.23Allen, B.J. 2025. Central Sierra: Virtual Fencing Directs Cattle to Graze Medusahead Grass on California Rangeland. University of California Center for Natural Resources. Accessed 12/12/2025. And precise grazing can be used to create fuel breaks in some ecosystems, mitigating fine fuel for wildfires and decreasing fire severity.24Boyd, C.S., O’Connor, R.C., Ranches, J., Bohnert, D.W., Bates, J.D., Johnson, D.D., Davies, K.W., Parker, T. and Doherty, K.E., 2023. Using virtual fencing to create fuel breaks in the sagebrush steppe. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 89, pp.87-93. Providing livestock access to water is critical to operational success, and it can be targeted to areas with substrates that are more resistant to trampling. Virtual fencing offers livestock producers the adaptability to concentrate livestock without the need for permanent or temporary hard fences.

3. Time livestock rotations to improve habitat and reduce wildlife conflict

Flexible, digital boundaries allow for many other potential innovations, including increasing habitat heterogeneity and soil quality via rotational grazing, or even moving livestock to follow seasonally varying resources (e.g., upward in elevation in the spring). Targeted and rotational grazing can also be used to shape plant community composition and heterogeneity, including to increase biodiversity.25Davies, K.W., Boyd, C.S., Bates, J.D., Svejcar, L.N. and Porensky, L.M., 2024. Ecological benefits of strategically applied livestock grazing in sagebrush communities. Ecosphere, 15(5), p.e4859. They also allow for seasonal avoidance of migrating or reproducing wildlife. Once the effectiveness of virtual fencing is better known in the conservation community, many creative approaches could be unleashed to take advantage of its dynamic capabilities. These types of rotational or seasonal movements would be difficult and expensive with physical fences or human herders.

4. Exclude livestock from sensitive areas to minimize grazing impacts

Virtual fencing could also allow for much more precise and dynamic livestock exclusion from sensitive areas such as riparian zones, known wildlife migration corridors, or critical seasonal wildlife habitat such as sage grouse leks or breeding sites. This ability to “precision exclude” livestock from sensitive areas is particularly relevant to producers using public grazing allotments, where the ability to demonstrably avoid protected species and areas may allow them to continue to access allotments that would otherwise be unavailable to them.

Additionally, virtual fencing would allow for these exclusionary practices without the need for physical fences. Physical fences, particularly those along riparian corridors, can further fragment landscapes and create difficulties for wildlife trying to access water sources.

Potential Future Conservation Applications

By researching and piloting novel conservation applications of virtual fencing, conservation groups can leverage the technology to generate additional benefits in the future:

5. Improve administration and impact of conservation grazing programs

Virtual fencing has the potential to streamline and automate conservation grazing programs in several additional, interesting ways. One is by improving the administration of conservation grazing programs that pay livestock producers for shifting livestock locations or the timing of rotations.26Wätzold, F., Jauker, F., Komainda, M., Schöttker, O., Horn, J., Sturm, A. and Isselstein, J., 2024. Harnessing virtual fencing for more effective and adaptive agri-environment schemes to conserve grassland biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 297, p.110736. These conservation strategies currently face cost and logistics challenges stemming from the measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of impact. Virtual fencing could help reduce these MRV burdens for both ranchers and the conservation groups and agencies providing the payments. The combination of digital boundary setting and livestock location data means ranchers could more easily measure and report, and conservation groups and agencies more easily verify, that grazing practices changed. Likewise, regulatory compliance with range management plans will also likely become less burdensome for both producers and agencies. For example, cattle are currently excluded from grazing on public land for two years post-wildfire in sage-steppe ecosystems. This means that producers must either keep their livestock out of an entire physically fenced paddock within a grazing allotment or install new physical fencing to partition the area. With virtual fencing, cows can be excluded from burned areas easily, effectively, and measurably.27Boyd, C.S., O’Connor, R., Ranches, J., Bohnert, D.W., Bates, J.D., Johnson, D.D., Davies, K.W., Parker, T. and Doherty, K.E., 2022. Virtual fencing effectively excludes cattle from burned sagebrush steppe. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 81, pp.55-62. Importantly, conservation benefits can be realized even when livestock do not obey virtual fencing perfectly.28Silber, K.M., Dodds, W.K., Mushrush, C.R., Capizzo, A.P., Gibler, G., Burnett, E., Moriello, M.E. and Boyle, W.A., 2025. The effectiveness of using virtual fencing for cattle to achieve conservation goals in tallgrass prairie. Rangelands, 47(1), pp.50-60.

6. Reward “conservation mode” within virtual fencing software

Similarly, conservation could be streamlined or included as a default mode in virtual fencing software. Virtual fencing companies could collaborate with conservation groups and agencies to create easy-to-use “conservation modes” within virtual fencing software, for example by mapping riparian buffers and other sensitive areas to exclude livestock from them. Ranchers could then be compensated by conservation groups for using such a mode. Relatedly, virtual fencing software could facilitate landscape-wide programs to pay producers for changing grazing practices, with goals such as increasing landscape connectivity in migration corridors, jointly administered and funded by government and private actors, with shared goals, maps, and monitoring and agglomeration bonuses for neighboring landowners who jointly participate.

Catalysts of Conservation

How can the conservation community accelerate the use of virtual fencing as a transformative conservation tool? Virtual fencing’s conservation potential will not be fully achieved unless it is first and foremost widely accepted and adopted in the ranching community, and ranching as a livelihood is economically successful and durable across generations. Adoption at scale depends on ranchers first trusting the technology. To achieve this, conservation groups can act as honest brokers, sharing successes as well as lessons learned and limitations. Conservation groups can also use their networks to convene conversations among producers, allowing peer-to-peer learning opportunities. Widespread adoption is important not only because it has direct conservation benefits, but also because it makes innovative conservation uses, such as new pay-for-practices programs, much easier and cheaper if virtual fencing is already used by a particular producer—or, better yet, an entire landscape of producers. For example, if a producer is already using virtual fencing, they may be more likely to think about enrolling in a conservation organization’s riparian-exclusion compensation program; likewise, if virtual fencing is widespread, a conservation organization seeking to develop such a compensation program would face lower costs and improved impact reporting. Essentially, promoting adoption of virtual fencing within the ranching community can become an effective conservation strategy, as can actively working to overcome barriers to adoption, whether related to lack of trust, learning challenges, lack of efficacy, or economic, social, and policy or legal barriers. Going further, conservation organizations or agencies can incentivize changes in grazing practices by providing virtual fencing access and technical assistance in exchange, as PERC is piloting in our Conservation Innovation Lab (Figure 3).

Virtual fencing may also increase the profitability and intergenerational durability of ranching as a livelihood in the face of increasing financial uncertainty in the agricultural industry. This would promote conservation by increasing the likelihood of working lands remaining operational, rather than being converted into “ranchettes” or another lower-conservation-value use. Currently, virtual fencing can benefit ranchers’ bottom lines in several key ways, including by increasing forage utilization, improving grazing distribution (e.g., rotational grazing), and reducing labor and capital costs of fence maintenance over time.29May, T.M., Burnidge, W.S., Vorster, A.G., Dalke, A.M., Aljoe, H., Lien, A.M. and Noelle, S.M., 2025. Is virtual fencing right for you? Producer considerations for successfully deploying and managing livestock with a virtual fence system. Rangelands, 47(1), pp.9-15. Locating lost animals is another important function, which should also reduce carnivore depredation, as well as increase the probability of cause-of-death determination, enhancing the ability to access compensation payment. Monitoring animal health and reproductive activity are promising new avenues for increased profit, although these functionalities are still in development.30Melo-Velasco, J., Wilson, K.R., Heimsoth, J. and Myers, R.L., 2024. “There will always be collars in my future”; Exploring US ranchers’ and company representatives’ perspectives of virtual fencing for livestock. Smart Agricultural Technology, 9, p.100632. Moreover, there is potential for virtual fencing as a novel digital technology to make ranching more appealing for the next generation of ranchers, a crucial factor for durable stewardship of working lands.

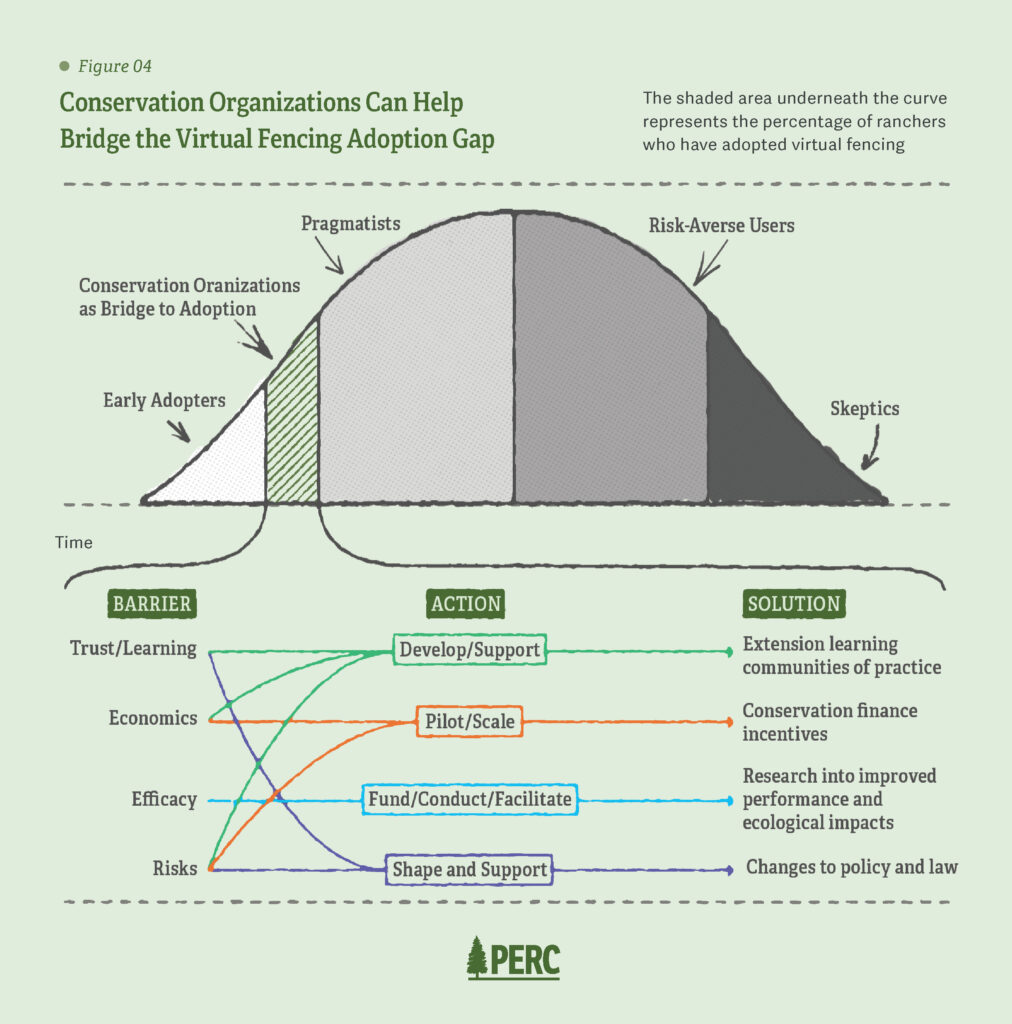

To achieve widespread adoption of virtual fencing technology and the resulting conservation functions and benefits, conservation interests must understand the barriers to producer uptake and contribute to overcoming them. In the U.S., adoption is still relatively low. Making the leap across the adoption gap, from “early adopters” who actively seek out and experiment with new technologies and methods to the majority of the ranching community, is a key next phase for unlocking conservation success. Success with early projects can have wide-spreading ripples, as can failures—the recovery time from setbacks with individual ranchers can be lengthy, and so beginning with a good plan and realistic expectations is critical. There are four major barriers to adoption: lack of trust, unworkable economics, lack of efficacy, and legal and policy risks. Conservation organizations can help dismantle all of them using four core strategies: expanding education, innovating financial tools, improving performance, and reforming policy (Figure 4).

Expand extension education and communities of practice

Educational extension and communities of practice can lower barriers across all four limiting factors. Ranchers currently do not have sufficient trust in virtual fencing technology, virtual fencing companies, government agencies seeking to increase uptake of virtual fencing, or conservation groups championing virtual fencing. The conservation community could help build trust and structures to expand knowledge in several ways. Fostering vibrant and growing communities of practice, in collaboration with industry groups and university extension faculty, would allow for knowledge transfer directly between practitioners. Hosting or supporting a repository of virtual fencing information and tooling would allow for asynchronous, digital learning. Leading virtual fencing education seminars and workshops from a conservation perspective but with explicit information on lessons learned and ranching performance metrics included alongside would also help increase trust and learning. Partnering with extension services and working ranches who have already adopted virtual fencing, to provide virtual fencing education from a purely agricultural perspective, will also increase trust and learning. These same actions would also reduce the real and perceived risks of adoption and reduce the economic uncertainty while clarifying the economic benefits and timelines for returns. For example, the University of Arizona, with support from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has invested heavily in a virtual fencing education center via the digital Rangelands Gateway, including tools to compare economic factors across virtual fencing companies, and educational opportunities and training.

Innovate, pilot, and scale conservation finance and incentives

Conservation groups can also pilot and scale conservation finance and cost-share programs for virtual fencing adoption, regardless of whether they are tied to a specific virtual fencing conservation practice. While virtual fencing can pay for itself, depending on a number of variables (see a simple cost calculator here), those payoffs sometimes do not occur for years, or at all. Currently, most ranchers must either self fund or finance the adoption of virtual fencing. Public funding is available for virtual fencing in some circumstances, for example, through NRCS EQIP grants in some areas, but coverage is not universal, and the future of such federal funding is unclear. Private conservation groups should consider offering new financing solutions that harness the broad conservation finance toolbox. Additionally, private conservation investments in the technology can tolerate higher risk and pave the way for more federal or state investment. For example, the PERC Virtual Fence Fund, in combination with direct support from Conservation Innovation Lab staff and partners within the academic research community, has proven to be critical for successful pilot projects. A recent analysis highlighted the importance of sharing initial costs in generating long-term net benefits for producers, making cost-sharing key to unlocking virtual fence scaling under current economic conditions.31Duval, D., Audoin, F., Dalke, A., Mayer, B., Antaya, A., Quintero, J., Blum, B. and Lien, A., 2025. Foundations of Virtual Fencing: Economics of Virtual Fence (VF) Systems. Thinking more broadly about the ranching system, conservation groups could consider financing intergenerational ranch ownership transfers as a conservation approach. Members of the next generation of ranchers may be more likely to become early adopters of “digital ranching” tools like virtual fencing than the current generation. All of these financial options could be combined with ongoing support, education, and community-building efforts to participating ranchers.

Fund and facilitate research to discover new functions and benefits

More research into virtual fencing-based conservation interventions could build a stronger body of evidence for virtual fencing efficacy while also providing opportunities to improve the technology. Evidence-based research may also address concerns related to trust in the technology, both from a producer standpoint, but also from conservation groups. Initial research has been very promising in terms of conservation outcomes, and interest in ranching and conservation functions of virtual fencing is producing a growing body of peer-reviewed research, such as a recent special issue in Rangelands. Yet even as virtual fencing systems continue to improve in terms of overall efficacy, there are many outstanding questions about the conservation impacts of the approach, including the unintended consequences. There are also novel, high potential, but risky applications, such as using virtual fencing approaches on lands with high-conflict-probability or highly endangered wildlife, which could steer collared cattle (or even collared wildlife) away from risky areas proactively rather than relying solely on our current “lagging indicator” tools, such as hazing, relocation, government-administered compensation funds, and lethal removal, to manage conflict. For example, virtual boundaries could exclude livestock from known carnivore dens or rendezvous sites, or herd them away from real-time locations of GPS-collared carnivores or wild herbivores like elk that can transmit disease or compete for forage. Camera traps are increasingly being fitted with “edge computing” software, allowing for near-real-time classification of images onboard the cameras, which send alerts to wildlife managers if certain species are detected.32Rastogi, S., Bhattacharyya, S., Vimal, K., Dinerstein, E., Shah, W.A., Nagano, Y., Hirari, S., Gulick, S., Lee, A. and Sekar, N., 2024. Promoting human–elephant coexistence through integration of AI, real‐time alerts, and rapid response. Conservation Science and Practice, p.e70186. If a “conflict risk” warning could be sent to livestock producers when specific types of wildlife are detected on cameras nearby, ranchers could dispatch range riders or digitally herd livestock away from the conflict area. The same principle could apply to other means of dynamically detecting conflict wildlife, such as acoustic sensors. Each study of a conservation function would also offer an opportunity to improve the technology and methods while simultaneously measuring animal welfare outcomes.

Foster policy change to increase adoption

Finally, for virtual fencing to reach its full potential for conservation, changes to state and federal policy and law will be needed. Responsibility for building and maintaining fences for livestock is widely variable across states and continues to change. Initially, when vast western rangelands were open and unfenced, most states’ grazing policies required landowners to “fence out” neighbors’ livestock. Since the days of the wide open range, some states have since shifted to require landowners to “fence in” their stock, although some fence-out state policies remain where there is designated open range. In yet other states, conditional fence-out laws apply, where the responsibility for fence maintenance is shared by a livestock owner on their land and by neighbors.33Orngard, S., 2024. Virtual Fencing: Pushing the Boundaries of Legal Livestock Fencing in the United States. Drake J. Agric. L., 29, p.137. Fence-in laws may be easier to adapt to virtual fencing than fence-out laws, since a livestock owner cannot control their neighbors’ herd with virtual fencing, whether or not the neighbor is using virtual fencing.

Likewise, federal grazing permits have historically been “use it or lose it,” and consequently, conservation organizations could not pay a rancher to reduce stocking rates or buy out their grazing rights.34Regan, S., Stoellinger, T. and Wood, J., 2023. Opening the range: reforms to allow markets for voluntary conservation on federal grazing lands. Utah L. Rev., p.197. Virtual fencing could provide a means for conservation organizations to pay a permit holder to institute conservation practices while remaining within the terms of their permit, in the absence of policy reforms allowing for secure and transferable grazing permits to conservation interests.35DeLay, N.D., Mooney, D.F., Ritten, J.P. and Hoag, D.L., 2024, September. Virtual Fencing: Economic and Policy Implications of an Emerging Livestock Technology for Western Rangelands. In Western Economics Forum (Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 54-64). Permanent virtual fencing tower installations on federal land would require permitting under NEPA and other relevant environmental laws,36Hoag, D.L., Reuter, R., Mooney, D.F., Vitale, J., Ritten, J., DeLay, N., Evangelista, P.H. and Vorster, A., 2025. The economic fundamentals of virtual fencing compared to traditional fencing. Rangelands, 47(1), pp.92-101. although a categorical exclusion, or use of moveable or temporary towers,37Stauder M. DIY Mobile Base Station Conversion Guide. EOARC Technical Bulletin 234. Oregon State University. could reduce this barrier.

Beyond grazing policy and law, there are also other legal barriers to virtual fencing adoption. Novel issues of liability exist for virtual fencing infrastructure, including towers, collars, batteries, and solar panels. Virtual fencing radio frequency towers or base stations are currently company specific, meaning ranchers must buy their collars and towers from the same manufacturer. Similar to the structure of cell phone networks, virtual fencing companies could consider brand-neutral towers to help scale the use of the technology. This could create concerns about security of trade secrets, which would need to be addressed. Additionally, local land use planning may offer another barrier to virtual fence deployment at scale. If virtual fencing towers are categorized similarly to radio towers or cell towers, it could limit their geographic placement to zoned areas. Given that virtual fencing is mostly used in rural areas, this concern seems unlikely to be relevant, but if livestock producers near communities want to consider using virtual fencing, they should be sure to confirm they are not in violation of any local zoning or land use laws. Trespassing law is also relevant, because physical posting of no-trespassing signs often relies on fencing, and open gates and lack of fences typically conveys open access to the uninformed. Electronic posting (also known as “e-posting”), which is already used in North Dakota, allows landowners to post legally sufficient notice that public access is prohibited through digital platforms rather than physical signage. When combined with virtual fencing, e-posting enables the removal of unnecessary fences and the use of open or wildlife-friendly gates, enhancing wildlife connectivity while giving landowners more flexible, cost-effective tools to define and enforce private property rights.

In the future, virtual fencing could ease the way for best practices in range management to be more easily implemented by ranchers on all land and more easily monitored where applicable on public land. For example, virtual fencing could exclude livestock from digitally mapped riparian buffers in accordance with land management plans and the Clean Water Act, and collared livestock could be easily monitored. Recent studies show promising results in terms of potential for successful livestock exclusion from riparian zones, even in arid systems.38Mayer, B., Dalke, A., Antaya, A., Noelle, S., Blum, B., Blouin, C., Ruyle, G., Beard, J.K. and Lien, A., 2025. Using virtual fence to manage livestock in arid and semi-arid rangelands. Rangelands, 47(1), pp.24-33. But with virtual fencing and physical fencing alike, exclusion from sensitive areas is not guaranteed because some livestock will inevitably cross fence boundaries. Compared to hard fences, virtual fences make it easier to detect breaches of boundaries around sensitive areas. Detection of these virtual breaches, therefore, may suggest to range managers that virtual fencing is not effective and suggest to ranchers that virtual fencing presents a risk to their grazing permits—unless grazing policy is clarified as it pertains to virtual fencing. Data privacy may also be a concern on federal land, if the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) is interpreted as applying to virtual fencing data from digital platforms shared by ranchers and grazing allotment managers employed by the federal government.

Virtual fencing could reduce costs for federal grazing permit holders, who are often responsible for maintaining hard fences and other infrastructure, which can increase grazing costs to similar levels as those of private grazing leases.39DeLay, N.D., Mooney, D.F., Ritten, J.P. and Hoag, D.L., 2024, September. Virtual Fencing: Economic and Policy Implications of an Emerging Livestock Technology for Western Rangelands. In Western Economics Forum (Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 54-64). Paying for virtual fencing could also be considered a range improvement on federal grazing land, potentially opening another avenue to fund installation of the virtual system. The range betterment fund, created by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), sets aside half of grazing fees for range improvements, such as fence construction, weed control, water development, and fish and wildlife habitat enhancement. Funding virtual fencing via the FLPMA or by conservation organizations, along with water development to replace access to virtually excluded riparian areas, could be a high-return conservation investment.

Practical Project Recommendations

After more than two years of experience piloting more than 10 projects using virtual fencing to achieve various conservation goals (Figure 3), PERC has learned valuable, practical lessons regarding how to structure contracts, build needed relationships, and monitor virtual fencing outcomes, as detailed below.

For a conservation group considering a virtual fencing program, we recommend the following, based on PERC’s experience with our virtual fencing pilot program, as well as our partners’ and collaborators’ experiences:

Structure sound contracts with landowners:

- Avoid blanket virtual fence contracts.

- Determine the operational and/or conservation benefits that the landowners or managers want to create.

- Build monitoring plans and contracts around landowner and manager goals.

- Structure initial contracts around changes in grazing practices, not conservation goals, until the practices-to-outcomes pathway is well established.

- Allow ranchers to maintain ownership of virtual fencing data and technology.

- Fund flexibility, so that producers can spend funds on towers, collars, or both, depending on their needs.

Build relationships with virtual fencing companies to ensure:

- Virtual fencing companies understand conservation as a source of funding for projects.

- Conservationists, ranchers, and virtual fence companies can set expectations early.

- Eventually, companies structure tech/software to include evidence-backed conservation settings.

- Pilot projects are used to build relationships with companies and help them test new conservation functionality in a low-risk way.

- Ranchers connect with companies most likely to help them succeed.

- Industry groups are established to share insights between conservation, ranching, and virtual fence companies and researchers.

- Conservation groups can be honest brokers and understand when virtual fencing may not be the right decision for a producer.

Monitor virtual fencing projects in the following ways:

- Start with a learning period for ranchers, preferably one year.

- Then work with ranchers to determine agriculture goals, and select conservation goals that overlap.

- Start by focusing on one or two conservation goals.

- Carefully consider the seasonality of conservation goals—some are better suited for summer, others for transition periods in spring and fall.

- Monitor and reward inputs—changes in grazing management practices enabled by virtual fencing—and not only conservation outcomes.

Conclusions

Livestock grazing on rangelands is highly compatible with robust wildlife populations. Supporting working rangelands and their stewards, while also working to improve practices with conservation in mind, is a win-win for all. Conservationists have an opportunity to catalyze the adoption of virtual fencing, a transformative technology that maintains the boundaries necessary for successful livestock operations, while also unlocking a number of new conservation benefits. Virtual fencing can improve conservation outcomes by reducing the need for physical infrastructure, concentrating and locating livestock, excluding livestock from sensitive areas, and timing grazing rotations to increase flexibility and habitat heterogeneity. Applied as a broader conservation tool, virtual fencing could potentially automate conservation via a “conservation mode” within virtual fencing software to reduce monitoring, reporting, and verification burdens for conservation grazing programs.

Key to unlocking this conservation potential is getting virtual fencing to be price- and performance-competitive with physical fencing, and promoting widespread adoption so that ranchers can more easily be engaged in virtual fencing-dependent conservation practices. To help increase adoption of virtual fencing among the ranching community, conservation organizations and agencies can help dismantle economic, social, and efficacy barriers to adoption through four strategies: 1) developing and supporting extension services and communities of practice; 2) piloting and scaling conservation finance tools; 3) funding and facilitating research into improved reliability and conservation impacts; and 4) shaping and supporting policy change. In a world with escalating fragmentation of and disturbances within ecosystems, virtual fencing and related technologies can help conservation keep up and accelerate positive impact.