Road maintenance required near the Firehole River in Yellowstone National Park.

Reed Watson provided testimony to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Natural Resources – Subcommittee on Federal Lands on “Identifying Innovative Infrastructure Ideas for the National Park Service and Forest Service” on March 16, 2017.

Introduction

Chairman Bishop, Ranking Member Grijalva, and Members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify on the important topic of federal lands infrastructure. My name is Reed Watson and I am the Executive Director of the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), a nonprofit research institute in Bozeman, Montana, that has studied public land issues for more than three decades.

My testimony today will describe several ideas Congress should consider if it hopes address the infrastructure needs of the National Park Service and the National Forest Service. None of these proposals rely on increased congressional appropriations, nor the privatization of federal lands. To the contrary, they would keep federal lands in federal hands while freeing our national parks and forests from the legal burdens that have made both agencies dependent on congressional appropriations and unable to maintain their infrastructure.

By removing unnecessary restrictions on revenue generation, collection, and spending, Congress can empower federal land agencies to be more fiscally self-sufficient. While maintaining federal ownership, the infrastructure on our federal lands can be managed in innovative ways that decentralize management decisions, cut maintenance costs and delays, and ensure access for future generations of recreationists and sportsmen.

Infrastructure in Collapse

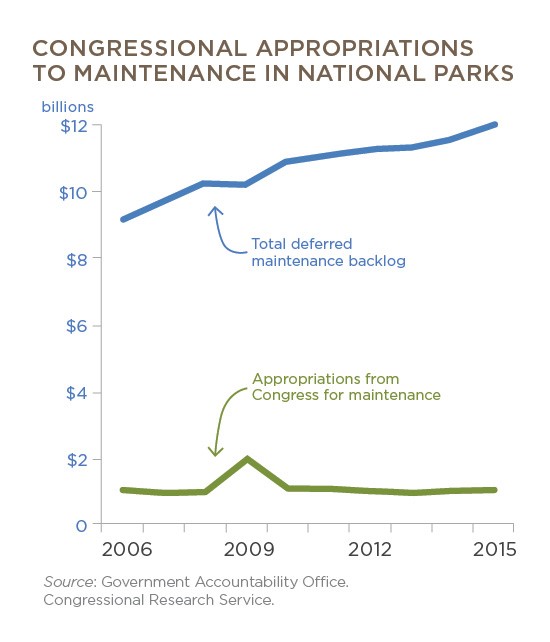

The National Park Service recorded a record-breaking 331 million visits during the agency’s centennial year in 2016, a 7.7 percent increase over 2015.1 This visitor growth is worth celebrating, but it has taken a significant toll on the agency’s infrastructure. Estimated at $12 billion, the Park Service’s maintenance backlog refers to the total cost of all maintenance projects that were not completed on schedule and therefore have been put off or delayed. The backlog is now nearly four times higher than the agency’s latest budget from Congress, and it has emerged as one of the major issues facing the Interior Department.2

Historically, Congress has not prioritized maintenance in national parks, choosing instead to prioritize the creation of new parks. The number of park units managed by the Park Service has grown significantly over the past decade—from 390 in 2006 to 417 today. Meanwhile, the agency’s overall budget, as well as the amount of funding devoted to maintenance projects, has remained relatively constant. Hence, funding for the deferred maintenance backlog makes up only a fraction of the annual appropriations the National Park Service receives from Congress each year.

Over the past decade, Congress allocated approximately $1 billion on average each year for maintenance projects in national parks.3 But that amount has covered only a small fraction of the National Park Service’s infrastructure needs, and the maintenance backlog grew by 31 percent during the time period. Unless changes are made, the National Park Service estimates the backlog will continue to increase as new units are created and its existing assets continue to deteriorate.4

A similarly dire situation exists on Forest Service lands, where the deferred maintenance backlog stands at a staggering $5.1 billion.5

Addressing the deferred maintenance of federal lands infrastructure will require innovative thinking in terms of both revenue generation and spending. It will also require a critical appraisal of congressional funding priorities and the laws that explicitly encourage the acquisition of new federal lands over the maintenance of existing federal lands and infrastructure.

Fee Collection to Align User-Manager Incentives

To repair and maintain infrastructure on federal lands, the National Park Service and National Forest Service will have to become less dependent on congressional appropriations and more fiscally self-sufficient. That means relying on infrastructure users for a larger portion of their respective operating budgets.

Today, the majority of user fees can be retained where they are collected, rather than being sent back to the U.S. treasury, providing park and forest managers with an important—albeit insufficient—funding source to address infrastructure maintenance without relying entirely on congressional appropriations.6 However, the authority to collect fees is temporary and unnecessarily narrow.

Enacted in 2004, the Federal Lands Recreation Enhance Act (FLREA) originally sunset in 2014 and has since been only temporarily renewed.7 As currently written, FLREA specifically prohibits the Secretary of the Interior from charging entrance fees for federal recreational lands and waters managed the National Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, or the Bureau of Reclamation. The law does allow, but strictly limits, the Secretary’s authority to charge “standard” and “expanded amenity recreation fees” on these lands.8 Consequently, user fees and donations comprise approximately 12 percent of the National Park Service’s annual budget, with annual appropriations making up the rest.9

Congress should act to permanently reauthorize federal land agencies to collect entrance and recreation fees and to expand the discretion of park superintendents and forest rangers to set their own fee schedules without having to obtain additional approvals from Congress or the Secretary. For example, park superintendents could be given the discretion to charge higher fees during holiday weekends and other popular times, thus allowing them to collect more revenue for maintenance and use prices to limit congestion.

According to the Inspector General’s Office of the Department of Interior, “over the years NPS has proven itself reluctant to raise its entrance fees. Uncertainty over whether FLREA will be repealed or reauthorized hampers NPS’ flexibility in managing its Recreation Fee Program, including setting and adjusting park fees, which in turn has seemingly provided a disincentive to raise visitor fees.”10

Federal land managers should also have full discretion to charge entrance fees, recreation fees, and even tolls without congressional limitation. Land managers at the collection sites have a more accurate understanding of what forest and park visitors are willing to pay for than Congress does. Giving them full authority to charge fees, set their own fee schedules, and retain those fees on site aligns the incentives of infrastructure managers and users. It also provides federal land managers with a funding source for infrastructure maintenance that varies with visitation and use instead of congressional priorities.

Federal Funding for Conservation, Not Expansion

Another important source of funding for federal lands is the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), yet the majority of LWCF appropriations have actually exacerbated the federal lands infrastructure crisis by stretching the agencies’ maintenance budgets over an ever-expanding the federal estate. First passed in 1965, the LWCF aims to “preserve, develop, and ensure access to outdoor recreation facilities to strengthen the health of U.S. citizens.”

Each year, Congress devotes $900 million to the LWCF, largely derived from offshore federal oil and gas lease revenues, although any actual spending under the program must be appropriated by lawmakers. The funds are appropriated for three general purposes: federal land acquisition, state-level matching grants for outdoor recreation projects, and a third catch-all category referred to as “other federal purposes.”

The annual funds appropriated through the LWCF for these multiple purposes have varied substantially over time, with the majority of the appropriations ($10.5 billion or 61 percent) spent on federal land acquisition. This federal portion of LWCF funding can only be used for land acquisition by federal land agencies; it cannot be used for routine maintenance or operations, or to enhance access opportunities on existing public lands. So while the LWCF allows the federal government to purchase more land, it provides no means of taking care of those lands—nor does it address the critical needs that exist on the hundreds of millions of acres the federal government already owns.11

The program is set to expire in 2018, and its potential reauthorization has been the subject of recent debate. If Congress hopes to improve infrastructure on federal lands, it should first sharply reduce the level of federal land acquisitions. If additional land acquisitions are made, Congress should ensure they are done in a way that does not place additional financial burdens on already-overburdened land agencies.

Secondly, Congress could redirect LWCF appropriations to address critical needs on existing federal lands, including deferred maintenance, habitat restoration, management shortfalls, and legally acquired access across private land. This could be done by clarifying the criteria for appropriating LWCF funds to the “other purposes” category to include infrastructure maintenance.

Concession Contracting and Park Franchising

Federal land agencies currently have the authority to contract with independent parties for infrastructure maintenance and other services, however, that authority and the terms of concession contracts is needlessly prescribed by law. For example, the National Park Service Concessions Management Improvement Act of 1988 details the criteria by which the park service can consider concession proposals, the criteria for selecting the best proposal, and the maximum amounts and term of any contract awarded.12

Limiting the discretion of federal land managers in this way needlessly slows and increases the cost of even basic infrastructure maintenance.13 Federal land agencies and their employees should be free to outsource routine management operations of various public lands to the private sector while maintaining public ownership and oversight. Over the past three decades, these types of public-private partnerships have proven successful for the U.S. Forest Service, which today uses private operators to manage and maintain more than 1,000 of its campgrounds.

Performance-based contracts can be designed so that a managing federal agency defines site rules, parameters for visitor fees, management goals, and maintenance expectations. The contracted lessee would then collect visitor fees, maintain resources and facilities, and pay a portion of receipts back to the managing agency.

Under this approach, private contractors have a financial incentive to provide good stewardship of the site or road and to be accountable to visitors to ensure high-quality experiences. They are dependent upon the revenues they earn to cover costs, while also being held accountable by their contract with the federal land agency providing oversight.

A more significant management innovation involves the development of a national park franchising system. For properties proposed as new additions to the national park system, franchise agreements could be struck between the National Park Service and private management parties. Franchised parks would be held under the National Park Service umbrella but individually managed by non-profit organizations, businesses, or individuals.

With congressional authority, the National Park Service would set franchise requirements, and interested parties would create management plans that satisfy those requirements. Some franchise parks could also be required to be financially self-sufficient, whether funds were acquired through user fees, partnerships, or donations. A franchise could give park units the flexibility to manage for local priorities as determined by on-the-ground managers, the protection and status provided by the national parks brand, and the incentives to meet visitors’ desires at low cost.

Conclusion

It is ironic and unfortunate that many of the laws and regulations intended to enhance the value and accessibility of our national parks and forests are, in fact, accelerating their deterioration. If Congress hopes to address the infrastructure issues facing our federal land agencies, it would be wise to remember the words of Nobel laureate Milton Friedman, who said “One of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results.”14

Without increasing appropriations, Congress can empower our federal agencies to restore and maintain their infrastructure by simply removing the legal requirements that made infrastructure maintenance unlikely, if not cost prohibitive. Harnessing user fees, redirecting LWCF funding, expanding concession contracts, and rolling out park franchising can provide our federal land agencies with the means to address the current deferred maintenance backlog.

Video of Reed Watson’s testimony is available here.

For more information on deferred maintenance and public lands, check out A New Landscape: 8 Ideas for the Interior Department and Breaking the Backlog

2. “NPS Deferred Maintenance Reports, FY 2015.” National Park Service.

3. “National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve Efforts.” Government Accountability Office. December 2016.

4. “Deferred Maintenance Backlog.” National Park Service, Park Facility Management Division. September 24, 2014.

5. “Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2005-FY2014 Estimates.” Carol Vincent Hardy.

6. Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act. 16 U.S.C. 87.

7. Ibid, at § 6809.

8. Id., at § 6802.

9. “National Park Service: Revenues from Fees and Donations Increased, but Some Enhancements Are Needed to Continue This Trend.” Government Accountability Office.

10. “Review of the National Park Service’s Recreation Fee Program.” Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of the Interior.

11. For further discussion, see “5 Myths About the Land and Water Conservation Fund” by Robert H. Nelson, Shawn Regan, and Reed Watson. PERC Policy Brief. April 28, 2016.

12. National Park Service Concessions Management Improvement Act of 1988. 16 U.S.C. 5901 § 403-4.

13. “NPS Transportation Innovative Finance Options.” National Park Service and Department of Transportation.

14. “The Open Mind.” Interview with Richard Heffner. Public Broadcasting Service. 1975.