From Arizona to Swaziland, entrepreneurs are flourishing. Entrepreneurs are applying their talents and the tools of the marketplace to the protection of landscapes, wild animals, and even historic buildings. On these pages, meet a few of these enviro-capitalists.

A Passion for Trees

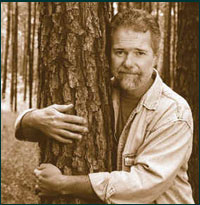

Chuck Leavell

Chuck Leavell is a highly admired pianist who plays rock and roll, blues, gospel, and country. He has toured with the Rolling Stones for two decades and accompanies artists from Eric Clapton to George Harrison.

Leavell and his wife Rose Lane Leavell also own Charlane Plantation in Dry Branch, Georgia, where they have achieved high standards of forest management. They were named the National Outstanding Tree Farmers of the Year in 1999 by the American Forest Foundation. For their stewardship, the Leavells have been honored by organizations such as the National Arbor Day Foundation, the Georgia Wildlife Association, and others.

The Leavells entered forestry in 1981 when Rose Lane Leavell inherited a family plantation. Rather than row crops, they decided to grow trees. Chuck Leavell started learning about forests, studying his correspondence course while on tour.

Today Leavell is a prominent forester who sponsors educational tours, supports a scholarship fund, and lectures at universities. A spokesman for good forest management, he has written a book, Forever Green, to promote responsible forestry and improve understanding of today’s forest conditions. On the cover, Mick Jagger writes: “Chuck is always talking about trees on tour . . . sometimes it drives me crazy!”

Water’s Emerging Market

Andrew Purkey

By Clay Landry

Andrew Purkey did not not simply position himself in an emerging market. He helped to create one. He is a major figure in the growing market for instream flows.

In the western United States, small streams that are vital for fish and other wildlife can dry up within weeks when drought hits. One reason is that farmers and ranchers may be using the water to grow crops, and in dry

Purkey has also worked with state officials to change the law to give Oregon landowners more options for keeping water in streams and protecting their rights at the same time. He has obtained water donations and has pioneered ways of valuing water rights. His work has inspired others to create water trusts in Washington and Montana.

Bringing Nature Home

Peter O’Neill

By Matthew Brown

Today it is not surprising to see affluent residential developments with creeks, woods, and wildlife. But that was not the case when Peter O’Neill began the River Run development in Boise, Idaho, in the late 1970s. “The whole essence of River Run was to maximize the natural environment,”

Wild animals have welcomed River Run. “The ultimate compliment is that we’ve had a number of beaver dams on the artificial creeks,” says O’Neill. “Bald eagles, ducks, kestrels, songbirds and geese, both migrating and resident, are found in the area.”

O’Neill could have left it at that—a scenic, wildlife-rich development that also made money. But he did more, turning an ugly Corps of Engineers canal into a trout-spawning stream. Few know the challenges he faced in obtaining government approvals of this novel idea.

River Run has won a number of awards, and O’Neill should be riding high. In a way he is. But new regulations supposedly designed to protect river banks and open space are proving to be new obstacles. “You simply could not afford to do all that we did with River Run because of the city ordinances,” he says.

Trophy Elk, Tribal Gain

Jon Cooley

By Terry L. Anderson and Donald R. Leal

Many American Indians live on reservations surrounded by spectacular beauty, yet poverty is a way of life. One tribe, the White Mountain Apache in east-central Arizona, has found a way to spur economic growth while protecting, enhancing, and using its natural surroundings.

The White Mountain Apaches’ hunting story goes back to 1977, when the state of Arizona was in charge of elk hunting on the reservation. Like most state game departments, Arizona sold a lot of permits at a low price. The tribe received none of the revenues.

That year, the tribal council took over management of hunting and fishing on the reservation. The tribe started sophisticated game management to allow elk to grow to trophy size. The first step was to cut the number of elk permits from 700 to thirty and raise the price to $1,500. The tribe also changed logging and cattle grazing practices on the reservation to benefit elk.

Elk have prospered, as has the reservation’s natural environment. In 2002, it will cost $14,500 to hunt for a trophy elk. But the tribe also holds inexpensive hunts for animals from javelina to wild turkey. It also protects the endangered Apache trout, and the recreation program provides job opportunities for young people.

Banking on Preservation<

Kent Gilges

By Jane S. Shaw

In the beautiful Clinch Valley in southwest Virginia, many landowners periodically clear-cut the wooded hillsides. The hills are too steep and their tracts too small to make money by selective cutting. So, from time

What if these owners could pool their land with others and receive a steady stream of income from the pooled property? That is the idea behind the Forest Bank, a business venture headed by Kent Gilges and developed by the Nature Conservancy. Gilges offers landowners who “deposit” their land in the Forest Bank a modest but reliable income over time. In return, Gilges will oversee management of all the banked properties, taking into account the ecology of the entire watershed. The Securities and Exchange Commission recently approved the formation of this bank, and the Nature Conservancy has set aside about $1.5 million to start the Clinch Valley process.

Gilges doesn’t stop there. He thinks that the Nature Conservancy should be supported by investors as well as donors. He wants to set aside some purchased land for preservation but let other tracts earn a return from logging or other uses that will keep money flowing in. That’s his next objective.

From Cloak Rooms to Brew Pubs

Mike and Brian McMenamin

By Clay Landry and Tim Fitzgerald

Taxpayer dollars are often poured into historic preservation, but Mike and Brian McMenamin do it themselves. The brothers, based in Portland, Oregon, are constantly saving old and decayed buildings, restoring them to a new use—as restaurants, hotels, and brew pubs—while

Edgefield, once a county poor farm in Troutdale, Oregon, is now a resort. McMinnville’s Old Oregon Hotel is thriving, and a former Masonic Lodge and retirement home in Forest Grove is now a destination resort, the Grand Lodge.

Portland has benefited handsomely. Its Kennedy Elementary School, closed for years and twice threatened by the wrecking ball, is now a hotel. The classrooms, named for their teachers, are guest rooms. Visitors can play basketball in the school gym, watch movies in the auditorium, and swim in the pool. (The Honors Bar features a smoke-free environment; the Detention Bar harbors smokers.)

And there are others. A Swedish tabernacle, the art deco Baghdad Theater, and the famous Crystal Ballroom, closed for nearly 30 years, have all been given new life. The motivation? As often with entrepreneurs, that remains a mystery: “We’re just looking to have place to sit and have a beer,” says Brian.

Full color copies of the December 2001 PERC Reports – Enviro-Capitalists for the 21st Century – are available at PERC.