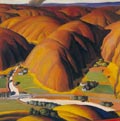

Gary Libecap, an economic historian at the University of Arizona, studied the Los Angeles Water Board purchases of land and water in Owens Valley, California, between 1905 and 1935. Los Angeles transported the water across the state through the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

Today, these purchases are viewed as theft. In the words of the Economist magazine (July 19, 2003, p. 15), they are the “most notorious water grab by any city anywhere” and their legacy has “poisoned subsequent attempts to persuade farmers to trade their water to thirsty cities”.

In “Rescuing Water Markets: Lessons from Owens Valley,” Libecap reveals that the emotion surrounding the trades has distorted the facts. Yes, property values in Los Angeles grew enormously as a result of the purchases—Los Angeles County land and buildings increased in value by nearly 600 percent between 1900 and 1930. But so did the values in Owens Valley! Although the property values were much smaller in total, they, too, rose by about 600 percent. That increase far exceeded the increase in property values in nearby agricultural counties that kept their water.

Owens Valley farming changed from crops to livestock, but the value of agricultural production did not fall much between 1910 and 1930. The Owens Valley landowners “did better by selling to Los Angeles than remaining in irrigated agriculture,” says Libecap.

Initially, both Los Angeles officials and the farmers wanted to make deals. The fast-growing city needed water and the Owens Valley farmers saw financial opportunity in selling their land. But the negotiations proved contentious, bitter, and occasionally violent. Libecap says that the sordid image surrounding the trades began to develop after negotiations stalled and Owens Valley farm- used negative publicity to pressure the city to pay higher prices.

At the same time, there were genuine problems in reaching deals. These were practical hurdles that any water trades must face. In economists’ lingo, they are: valuation disputes, bilateral monopoly, and third party effects.

Valuation Disputes

Looking back on the Los Angeles/Owens Valley trades, we should not be surprised at the difficulty the two parties had in agreeing on the value of the lands and the water they contained. Farmers knew that their water would help make Los Angeles enormously rich, so they wanted to sell their land at prices reflective of that wealth. But Los Angeles officials thought themselves generous because they were offering more than the going price for land in Owens Valley.

Bilateral Monopoly

Each group held something of a monopoly. Only a single buyer—the Los Angeles board—was going after Owens Valley land. And Owens Valley farmers formed sellers’ pools that attempted to hold a united front on prices. Negotiations under these circumstances “are apt to drag on because there are few options for either the buyer or the seller,” says Libecap.

Third-Party Effects

When farm prices fell during the agricultural depression of the 1920s, people in the valley blamed the drop on the sale of farmland—even though few of the sales had been concluded by that time.

Similar difficulties are likely to crop up in water trading today. Now that the problems are identified, says Libecap, “the challenge is for entrepreneurs to come up with ways to overcome them.”

Jane S. Shaw is editor of PERC Reports. Gary Libecap’s paper can be found online.

This article was originally published in the April 2005 issue of U.S. Water News.