Friedman was ahead of his time when he suggested privatizing forests 36 years ago

Recollections by Richard L. Stroup

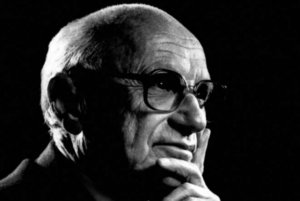

In 1971, John Baden and I attended the Mansfield Lecture program at the University of Montana in Missoula. Milton Friedman was the lecturer.

When Friedman landed in Missoula, retiring Forestry School Dean Arnold Bolle had just released the “Bolle Report” excoriating the forest service for mismanagement and environmentally ruining the forests they managed.

Friedman was asked by a reporter to comment on these allegations. His reply, in effect, was that we should remain calm and not do anything rash. Instead, he recommended taking several years—15 or 20 as I recall—to sell off the national forests so they would no longer be mismanaged. The audience was upset over his recommendation. John agreed with the crowd.

When Friedman gave a public talk the next day and opened the floor to questions, John jumped up from the audience and asked Friedman how he could possibly want to privatize the forests given all of the externalities—water quality issues, free rider problems, etc. Friedman asked John if he liked the way the public forest was being managed. John said “no” and went into more detail on the market failures. He knew far more about forests than Friedman, but Friedman knew about government weaknesses, and had good responses for John. The polite but earnest debate went back and forth for 15 minutes. I’d never heard of anyone standing up to Friedman for that long (nor have I since).

In any case, John and I continued to discuss the issue and, as a result, produced an article on privatizing the national forests. We went on to start a course at Montana State University-Bozeman titled “The Political Economy of the Environment.” Next came the idea to create the Center for Political Economy and Natural Resources. The center grew and evolved into the fine think and do tank it is today— PERC. We have Friedman to thank for inspiring us to apply markets to environmental problems back when nobody was considering the notion.

More recent thoughts on natural resource economics from Friedman

E-mail exchange between Milton Friedman and Robert L. Bradley Jr.

BRADLEY TO FRIEDMAN 9.06.03

Back around 1978 you wrote an essay, “The Energy Crisis: A Humane Solution” where you questioned the distinction between “renewable” and “nonrenewable” resources since oil, gas, and coal are “producible … at more or less constant or indeed declining cost because of the improvements in the technology of drilling and exploring and so on.”

This statement, during a time of record high oil and gas prices, was bold. It also predates most of the thinking of Julian Simon. The person making the point was Morry Adelman of MIT who remained focused on production costs unlike so many [Harold] Hotelling-inspired economists of the period.

1) How did you come to this view? Was it because of Adelman, your own reflections given a number of studies that came out from the Paley Commission (1952) and books from Resources for the Future in the 1960s, or both?

2) Do you believe there really is a natural resource economics in the sense that “depletable” resources have a fundamental difference from reproducible goods?

3) Do you believe, pending more research, that there might be an opposite “paradigm” (from depletionism) of resource expansionism where, indeed, natural resource prices on average can rise less than the rate of inflation because of the cascading effect of new knowledge and technology and expanding capital for mining? There is a lot of evidence right now that resource prices from the 19th century to the present have increased less than the general basket of goods, but I am wondering if there is something systemic that can be theoretically anchored in the “nondepletable” and indeed expanding nature of knowledge and capital (in capitalistic settings).

FRIEDMAN TO BRADLEY, 9.08.03

The basic point I believe in your natural resource discussion is that the economic product in question is not coal or oil or natural gas but energy.

The question is, what is the supply curve of energy? The use of coal or oil is simply a means of producing energy. The stock of coal, of oil, etc., is certainly in some sense finite, but that doesn’t mean that the potential amount of energy capable of being produced by whatever source is to be considered finite.

Energy will be produced in whatever way is cheapest at the time and as new means of producing energy are discovered the particular mode of producing energy will change from coal to oil to natural gas to atomic sources. That is the view expressed in the statement of mine that you quote.

In answer to your questions about that statement, I have absolutely no idea what led me to think of it except that it is straightforward simple economic analysis.

Regarding your second question, I do not believe there is a natural resource economics. I believe there is good economics and bad economics.

Three, I do not believe what is involved is an obvious “paradigm.” The question is a factual one whether the long-run supply curve of energy (or other natural resource output), whether it is upward or downward sloping, is trending down….

BRADLEY TO FRIEDMAN, 10.14.04

The categories “good” and “bad” economics may not go far enough in my view. I propose to take an additional step to delineate between technically correct (and worthwhile) economics and economics that is superior for real-world understanding and policymaking. There is a lot of economics that is technically correct but misleading, even diversionary. Such economics must be handled with great care, particularly with students and policymakers who need to get the big picture.

I believe that at least in an Economics 101 sense, “good economics” as you define it can be at odds. Here is my example:

Hotelling in his 1931 article “The Economics of Exhaustible Resources” complained that standard economic theory was “plainly inadequate for an industry in which the indefinite maintenance of a steady rate of production is a physical impossibility, and which is therefore bound to decline.” He did not qualify this statement elsewhere in the article and even brought in the real world relevance of his demonstration. Hotelling was wed to the fixity notion of resources, and not surprisingly, a whole literature developed in the 1970s looking for the depletion signal.

The collateral damage went further. Some economists at Resources for the Future, previously a bastion of expansive-resource thought, fell into the depletionist trap of predicting that oil and gas prices had to rise. And you know what [Jimmy Carter’s energy czar] James Schlesinger and others in government were saying. This came out of the seductive demonstration of Hotelling in part, maybe large part.

[Erich] Zimmermann’s “good economics”—which would have interpreted the 1970s price behavior in institutional terms—was completely lost in the debate, although Adelman and others brought in some of his ideas through the back door.

Thus as we return to a 1970s-type mentality, I am trying to resurrect Zimmermann’s approach as “better economics” to Hotelling’s “good economics.” I am trying to get the profession to not look for a “depletion signal” and focus on property rights and other institutional factors to explain the change in petroleum scarcity.

I believe that you see the approaches of Hotelling and Zimmermann both as good economics. Forgetting labels such as Zimmermann’s “functional theory” and Hotelling’s “fixity theory,” would you go so far as to say that Zimmermann’s approach is “superior” economics to Hotelling’s “good economics.” Perhaps there are two answers: one as a theoretical economist and one as a historian of economic thought…

Perhaps from the above there could be three rather than two categories: bad economics, correct economics, and good economics.

I appreciate this exchange and believe it will be a contribution to the history of economic thought.

FRIEDMAN TO BRADLEY, 10.15.04

If you use a tool that is designed well for one purpose for a purpose for which it is not suited, that does not detract from the goodness of the tool for its purpose. The same thing goes with economics. Hotelling’s analysis is good economics. If it is applied properly to the case of oil it produces the right result, namely that oil is not as an economic matter an exhaustible resource. That result follows from the Hotelling demonstration that an exhaustible resource will have a price that is rising over time. Since the price of oil was not declining over time, it is not economically an exhaustible resource.

Zimmerman’s using Hotelling properly and drawing the right conclusion rather than the wrong conclusion is good economics and to be applauded, but it is not a different kind of economics and it does not mean that his economics is superior to Hotelling’s economics…[But] I have no doubt that if [Hotelling] had applied his study of exhaustible resources and looked at the data, he would have come to the right conclusion from it.

I must confess that I tend to stay away from this kind of methodenstreit. I have always said that I would prefer to do economics to talking about how economics should be done or was done or is done….

Sincerely yours,

Milton Friedman

Visit www. friedmanfoundation.org for more information