Plenty of smart people are thinking about solutions to environmental problems and developing sound policy proposals. Why then is it so hard to get these practical solutions implemented? The first step to creating a law, of course, is to get a member of Congress interested enough to introduce the legislation to Congress. This step alone is difficult, but consider what happens after legislation is introduced. In the last Congress, 10,558 bills were introduced. Of these, only 464 became law—a success rate of just 4 percent.

Just what does it take to get a member of Congress to vote for environmental legislation?

Another measure of how difficult it is to pass environmental legislation is that the League of Conservation Voters (LCV), which rates members of Congress based on their votes to protect the environment, did not include the passage of a single piece of environmental legislation that subsequently became law in its 2006 ratings. They included votes on amendments to legislation and votes on legislation that never passed the Senate but not a single vote for a full piece of legislation that subsequently became law (and this in a time of unified Republican control of both chambers). So even with the proposals and sponsorship by a member of Congress, very few pieces of legislation become public law.

Party Matters

Just what does it take to get a member of Congress to vote for environmental legislation? First, party matters. We know from extensive research that members of Congress tend to vote with their party. For example, last congressional session, lawmakers voted with their party, on average, 88 percent of the time (Washington Post).

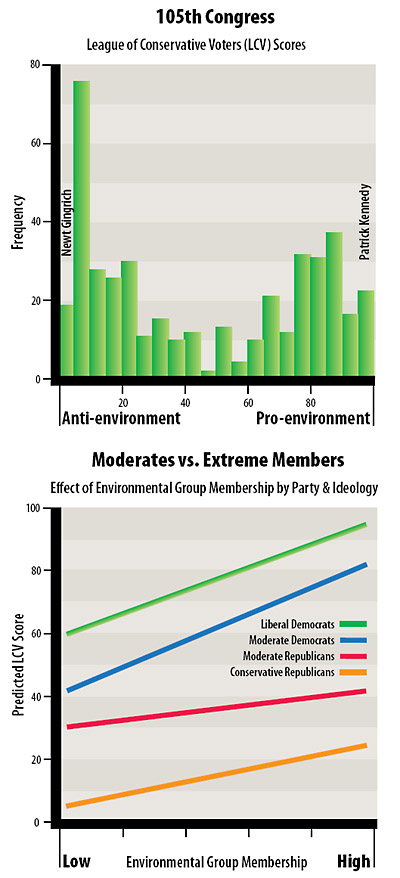

Democrats tend to vote for more environmental legislation than Republicans. The LCV’s average score for Democrats in 2006 was 66; for Republicans it was 26 (higher scores indicate greater agreement with the position of the LCV). But, controlling for ideology, the data show that the moderate Republicans vote more pro-environmental than the moderate Democrats. It’s counterintuitive but, when trying to get legislation passed, it makes sense to target moderate Republicans rather than moderate Democrats. The environment is an area of policy where moderate Republicans seem to have the freedom to select promising legislation and vote for it.

Moreover, the system of majority party control of the agenda means that a proposal must generally be supported by the majority party, or better yet, by both parties. A proposal that’s partisan, especially with the narrow balance of power, faces a tough battle. In this era of changes in party control, it makes sense to craft proposals that appeal to both parties.

Targeting Moderates

Second, ideology matters. More conservative representatives tend to have lower LCV scores, indicating that environmental issues separate along ideological lines in many cases. The baseline opinion of an individual member of Congress has an impact on whether that member will support legislation. For example, the 30 most liberal members of Congress in 2006, according to a measure derived from all votes in a year, have an average LCV score of 98. The 30 most conservative have an average LCV score of 7. Their universal ideology is a fairly good predictor of how they will vote on environment issues. On the other hand, the 30 in the middle of the spectrum have LCV scores that range from 0 to 92 and average 56. This confirms that the members to target are not those on either end of the spectrum, but the moderates whose votes can be swayed.

Constituencies Count

Finally, and this should be reassuring to us in our representative democracy, constituency matters. Members of Congress vote for more environmental legislation when they have more members of national environmental groups in their district (Anderson, 2007). If more of their constituents belong to environmental groups like the Sierra Club, National Wildlife Federation, the Nature Conservancy, and the Natural Resources Defense Council, members of Congress have higher LCV scores. Moreover, they are also influenced by such economic characteristics as employment in agriculture and mining. For a more concrete manifestation of this effect, consider Rep. José Serrano’s Bronx District, where there were only 25 Sierra Club members. If the Sierra Club membership in the Bronx would increase to 374, a statistical model would predict that Serrano’s LCV score would increase from 71 to 85, a vote for one more of the bills the LCV considered of environmental significance.1

In the area of environmental policy, the fact that constituency matters can complicate politics. Environmental policy often operates at the local level, but national environmental groups are big players in the national politics often required to influence legislation. These same national environmental groups are also effective at organizing at the local level. So, there can be a tension between the local and national constituencies.

While working as a staff member for a congressman, I saw this tension firsthand. In trying to provide additional protection for a threatened area of public land, we had support from the local stakeholders, including county commissioners, local citizens, and off-highway vehicle users groups. But, we failed to account for the organization of the national environmental groups. When they opposed the proposal, it failed. While all politics is local, the nature of environmental policy at the federal level means that all politics is also federal.

On the other hand, this sensitivity to constituent concerns should be heartening for those of us interested in solving environmental problems. Citizens consistently state in opinion polls that environmental protection is important. For example, a Pew Research Center poll in January 2007 found that 57 percent of respondents said that protecting the environment should be a top priority. Constituency opinion falls on the side of solving environmental problems, suggesting that there is pressure on members of Congress to vote for environmental legislation when it comes before them. In advocating for environmental legislation, we can cast it in terms of solving environmental problems and get support from voters, who in turn affect whether their members of Congress support the legislation.

Key Strategies

Once good policy has been proposed, research on Congressional voting suggests three key strategies. First, make it as bipartisan as possible. Why start with the opposition of almost half of the members of Congress? Second, target moderates and target moderate Republicans especially hard. These are the members whose votes on environmental legislation, given their ideology, can surprise observers of Congress. Third, work with local stakeholders, but involve the national environmental groups where possible. Members of Congress actually listen to the signals they receive from their constituents. By paying attention to the key strategies mentioned above we can influence the votes of members of Congress, increase that 4 percent success rate, and simultaneously improve the environment.

References

Anderson, Sarah. 2007. The Green Machine: Environmental Constituents and Congressional Voting. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association. August.

Washington Post. The U.S. Congress Votes Database. http:// projects.washingtonpost.com/congress/109/house/ party-voters/.