By Terry L. Anderson

[See research by Terry Anderson

and Dominic Parker]

But for an administration committed to integrating minorities into the mainstream of the American economy, Mr. Salazar will have to do more than manage natural resources. His department also oversees the poorest of all minorities: American Indians.

President Barack Obama courted the Indian vote. During the campaign, he visited Montana’s Crow Reservation last May and was adopted into the tribe under the Crow name "One Who Helps People Throughout the Land." There he said, "Few have been ignored by Washington for as long as Native Americans," and vowed to improve their economic opportunities, health care and education.

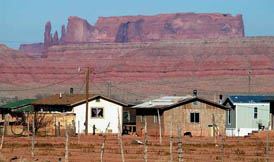

Two vital steps in this direction are to strengthen property rights and the rule of law on reservations. Virtually every study of international development shows that both of these are crucial to prosperity. Indian country is no different. The effect of insecure property rights is evident on a drive through any western reservation. When you see 160 acres overgrazed and a house unfit for occupancy, you can be sure the title to the land is held by the federal government bureaucracy. In contrast, when you see irrigated land in cultivation with farm implements, a barn and well-kept house, you can be sure the land is held in fee simple, whether by an Indian or non-Indian.

Land tenure in Indian country is complicated thanks to laws, dating back to the 19th century, which put millions of acres of tribal and individual Indian land under the trusteeship of the Interior department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs. These lands cannot be sold, used as collateral, easily inherited, or managed productively. Instead of giving Indians more federal welfare, Mr. Obama has the opportunity to increase their autonomy. It is, after all, their land. Let them manage it, borrow against it, and make it productive.

Some tribes have wrested control of the land from the bureaucracy and are demonstrating they can do better. On the Flathead Reservation in Montana, the tribally managed timber program netted $16 million between 1998 and 2005 — compared to $2.5 million for timber sales managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Also in Montana, the Crow tribe has negotiated a deal for a plant to convert coal to liquid fuels (such as jet fuel and diesel) that could generate revenues of $1 billion. That’s $80,000 per tribal member — not bad for a reservation where per capita income is $7,400.

Mr. Obama can also strengthen the rule of law in Indian country. Some reservations were placed under state jurisdiction in 1953: They have a stronger legal system than those with tribal jurisdiction, and they benefit economically. My own research, published in the Journal of Law and Economics, shows that for tribes with state jurisdiction, per capita income grew 20% faster between 1969 and 1999 than for their counterparts under tribal court jurisdiction. All Indians are less likely than whites to get home loans, but the likelihood of a loan rejection falls by 50% on reservations under state jurisdiction.

A stable judicial system is crucial for investment, and tribal courts have not provided this. Mr. Obama should set strict legal standards for tribal courts to meet, and if they don’t, they should have their legal jurisdiction turned over to state courts. This will sacrifice some tribal sovereignty, but it will help empower Indian economic well-being.

Mr. Obama’s rallying cry was "change," and that is exactly what he needs to bring about in Indian policy. The first Americans deserve to be freed from the bureaucratic shackles that have made them victims, and allowed to establish property rights and legal systems that can make them victors.