Editor’s note: The following is extracted from a talk by Patty Limerick (author of The Legacy of Conquest) delivered at a recent symposium celebrating the centennial of Wallace Stegner’s birth. Stegner, an American novelist, essayist, and environmentalist, is often called the “Dean of Western Writers.” His works include The Big Rocky Candy Mountain, Angle of Repose, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West, and The American West as Living Space.

Through the vitality and wisdom of his written words, Wallace Stegner remains an influential presence in the American West. When it comes to the consequences of aridity or the Western myth’s power to shape the behavior of its believers, no one is Stegner’s equal in expression. His fans and followers could take equal inspiration from his contradictions.

Angry as one may be at what careless people have done and still do to a noble habitat, it is hard to be pessimistic about the West.

Ardity

On the West’s lower rates of precipitation and higher rates of evaporation, Stegner’s quotable remarks are apt, forceful, and everywhere. In Marking the Sparrow’s Fall, describing life beyond the hundredth meridian, Stegner portrays a geographical line beyond which

. . . unassisted agriculture is dubious or foolhardy and beyond it one knows the characteristic western feel—a dryness in the nostrils, a cracking of the lips, a transparent crystalline quality of the light, a new palette of gray and sage green and sulphur-yellow and buff and toned white and rust-red, a new flora and a new fauna, a new ecology.

Stegner’s reflections on the color green carry particular punch. In his words, “You have to get over the color green; you have to quit associating beauty with gardens and lawns.” Contemplate that remark, and then think about the irony built in to a common habit of expression. The environmental movement uses the word “green” as a synonym for “environmentally friendly” or “compatible with and adapted to nature.” And yet, ladies and gentlemen, in the American West, green is the color of the Bureau of Reclamation. Green is the color of disturbed ground; it is the color of places where you have utilized water you have diverted from other places. Bright green, in other words, is the color of disturbance.

Western Myth

Stegner is equally thought-provoking when he takes on the power—and goofiness—of the Western myth. In a great passage from the essay, “History, Myth, and the Western Writer,” he speaks of what he calls the “amputated present” in Western writing:

I want only to underscore the point I made earlier about the absence of a present in western literature and in the whole tradition we call western. It remains rooted in the historic, the rural, the heroic that does not take into account time and change. This means that it has no future, either. Nostalgia, however tempting, is not enough; disgust for the shoddy present is not enough; and forgetting the past entirely is a dehumanizing error…Millions of Westerners, old and new, have no sense of a personal and possessed past; no sense of any continuity between the real Western past, which has been mythologized almost out of recognizability, and a real Western present that seems as cut off and pointless as a ride on a merrygo- round that can’t be stopped.… If you are any part of an artist, and a lot of people are some part of one…then I think you don’t choose between the past and the present, you try to find the connections, you try to make the one serve the other.

Stegner then puts an “Old Western” analogy to work:

In the old days, in blizzardly weather, we used to tie a string from house to barn so as to make it from shelter to responsibility and back again…. I think we had better rig up such a line between past and present.

With a clarity of vision that approaches the powers of x-ray, Stegner looked into the Western soul, and revealed the ways that Westerners themselves modeled their behavior on what they found in wild west dime novels, movies, and television shows.

Nobody devours Westerns more hungrily than the bona fide cowboy; nobody is so helplessly modeled by a fictional image of himself. What directly affects the cowhand indirectly affects people who have never had a close acquaintance with a horse or cow. A lot of clerks and soda jerks in western cities are partly what fact and history have made them and partly what the romantic imagination and traditional stereotypes tell them to be.

In an early phase of my own career, I put heart and soul into fighting the Western myth. Reading Stegner’s quotable words offered me a better understanding of why separating the myth from actuality proved to be such a tough and unrewarding task. Much of actual Western behavior has been shaped by people thinking they are riding the range as they go to work on Seventeenth Street in Denver and engage in stock transactions.

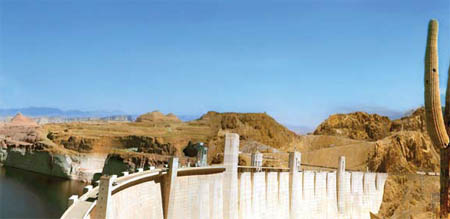

Everything about the dam is marked by the immense, smooth, efficient beauty that seems peculiarly American. Though no architect designed it and no one mind planned its massive details, it has the effect of great art.

And now we get to contradiction as an important feature of Stegner’s long-term legacy to Westerners. Our minds, like Stegner’s mind, are quilts and mosaics; our principles and convictions are hybrid, mixed, and rarely pure. In truth, when our thinking is pure, it is time to see a neurologist to see where the malfunction lies and if it is treatable. No one would find much to admire in a quilt or mosaic that was consistent, pure, and only of one texture or color. In the same way, it is a pretty dull literary heritage that is pure and consistent. In a writer’s work, some contradictions are sequential, the record of the changes in a person’s attitude through time. But some contradictions are simultaneous, reflecting the workings of a complicated mind and an equally complex soul. Rather than wincing over and trying to unsnarl the contradictions in an admired writer’s works, fans and followers are well advised to embrace them.

Stegner forthrightly put a spotlight on his own contradictions when he included the essay, “The Rediscovery of America: 1946,” in his collection, The Sound of Mountain Water. As he wrote in the preface,

These essays… probably show me getting my education in public. For example, I am amazed to find myself, in “The Rediscovery of America,” speaking admiringly of Hoover Dam and Lake Mead. I know better now, or at least know enough not to speak well of reclamation dams without looking closely at their teeth. But I have not changed the essay or any of the essays.

Good for him for leaving his early opinions on record, unchanged. Here is what Stegner said of Lake Mead. I do not quote this to mock it, to regret it, or to do any hindsight quarterbacking at all to it. One reason to let it stand is that the spirit in this passage is pretty close to what I myself felt in September of 2007, the last time that I was at Hoover Dam (called Boulder Dam at the time of Stegner’s visit).

Two days on Lake Mead and an afternoon and evening going through the Dam and the powerhouses have made boosters of us. Nobody can visit Boulder Dam itself without getting that World’s Fair feeling. It is certainly one of the world’s wonders: that sweeping cliff of concrete, those impetuous elevations, the labyrinths of tunnels, the huge power stations. Everything about the dam is marked by the immense, smooth, efficient beauty that seems peculiarly American. Though no architect designed it and no one mind planned its massive details, it has the effect of great art.

Stegner goes on to talk about the positive economic contributions of the Dam. Should his fans find all of this an embarrassment, as he himself did years later? In truth, I find more credibility and persuasiveness in critiques of reclamation written by authors who recognize and acknowledge the power, impressiveness, and even the beauty of the dams. Such critiques are more grounded and more realistic. Purity and consistency would produce mosaics and quilts of one color, and judgments of one dimension.

We are a wheeled people; it seems to me sometimes that I must have been born with a steering wheel in my hands…

That same essay from 1946 contains a passage that provides material for a fun guessing game. Read it aloud to friends, and ask them to guess which noted Western writer composed it, and I doubt you will get many winning guesses. In this passage, Stegner undertakes to tell us

…how it feels to be out on the road again, dry camping in the desert, hitting the road after five years of rationing and restrictions, doing what a good third of America is doing this summer of 1946, if the polls and the prophecies mean anything. For many people—and I sympathize with them—one of the least bearable wartime deprivations was the loss of their mobility. We are a wheeled people; it seems to me sometimes that I must have been born with a steering wheel in my hands, and I realize now that to lose the use of a car is practically equivalent to losing the use of my legs. Returning to the road after a layoff of several years is like re-establishing intimacy with a wife or a lover. There are a hundred things once known and long forgotten that crowd forward upon the senses, and there is the sharp thrill of recognition in all of them.

This is a fine summation of the seductiveness of the automobile, and it is an equally excellent reminder of our complicity with many of the structures and customs we have grown fond of denouncing. There are, after all, people in the Rockies who occupy the highest ground of environmental principle and who regularly put their mountain bikes or skis on their SUVs to drive to appropriate places to use that equipment. Since they are driving in a state of ideological grace, it may well be that their emissions are cleansed of carbon dioxide and other atmospheric troublemakers. Under these circumstances, it is great that a writer of Stegner’s standing gives us such a memorable tribute to the joy of driving a car through the Western landscape. That does not mean that we have to stick loyally and uncritically by that joy; in truth, this honest admission of complicity adds to Stegner’s validity and force as a critic of our habits.

I end with the most cited of Stegner’s legendarily quotable remarks, carrying a resonant phrasing that does indeed guide us through space and time. Stegner knew that much of what had happened in the American West had undermined or contradicted the hope he puts forward here. And yet, speaking of contradictions, it remains a sentiment worth our respect and attention.

Angry as one may be at what careless people have done and still do to a noble habitat, it is hard to be pessimistic about the West. This is the native home of hope. When it finally learns that cooperation, not rugged individuals, is the pattern that most characterizes and preserves it, then it will have achieved itself and outlived its origins. Then it has a chance to create a society to match its scenery.