As hundreds of bison make their annual winter migration out of Yellowstone National Park, most are hazed back into the park. Others are captured, quarantined, and occasionally slaughtered.

This year, more than 500 bison are being held by state and federal officials. If the bison test positive for brucellosis, a disease that can spread to livestock, they risk being killed.

However, new federal brucellosis regulations have the potential to change the hostile attitudes towards bison by state agencies and ranchers, who have long fought to keep bison inside Yellowstone and away from livestock rangelands. The new rules, released in December and open for public comment, may also lower the costs of bargaining between bison advocates, who want an expansion of bison wintering habitat, and nearby livestock owners.

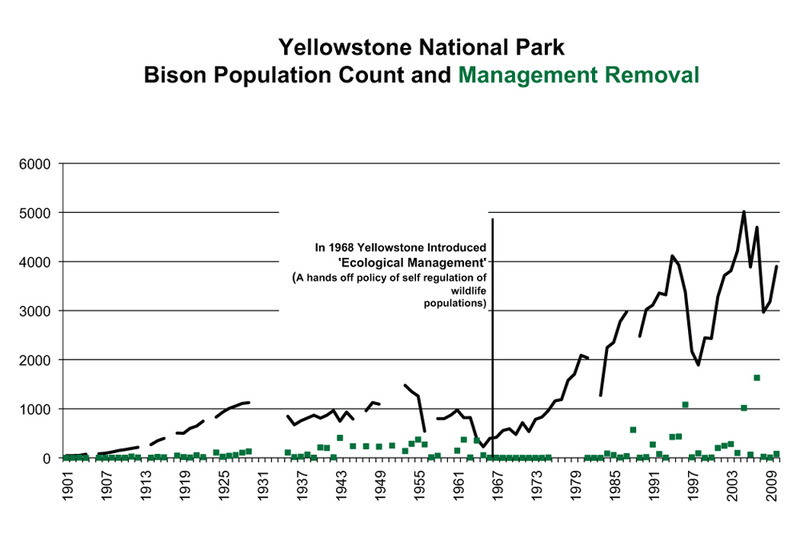

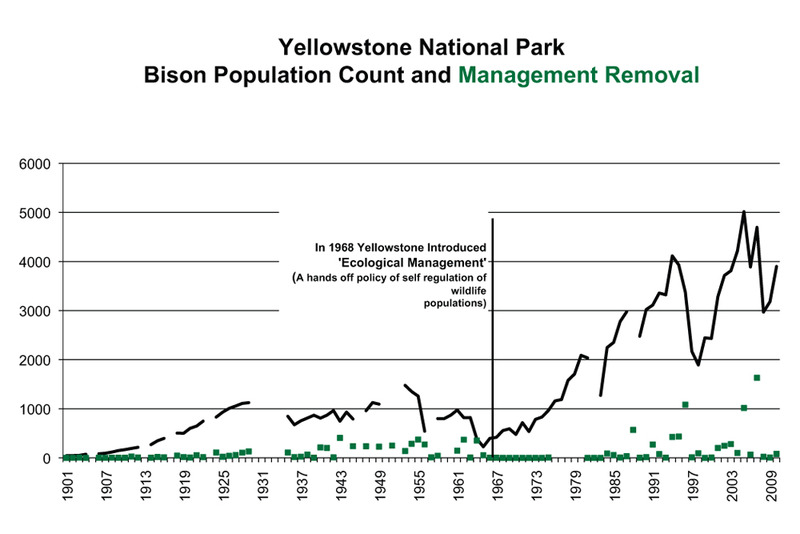

First, some background information. Bison once numbered in the tens of millions across North America. By the time Yellowstone was created in 1872, there were less than two dozen wild bison remaining. Aggressive park management resulted in rapid bison population growth throughout the first half of the twentieth century. So much growth occurred that culling the herd became necessary to maintain the population within the estimated carrying capacity of the park.

Opposition to the culling, however, brought changes to the park’s bison management policy. In 1968, an ecological management approach was introduced, leaving wildlife populations to self-regulate according to ecological conditions.

But Yellowstone is not a self-contained ecosystem for bison. As bison numbers increased, their required acreage increases as well—meaning that bison began to roam beyond the park’s borders. Without population control, Yellowstone’s bison numbers grew even more rapidly than before, from 556 in 1968 to as many as 5,015 in 2005.

Today, bison numbers remain high. The most recent survey counted 3,900. More bison means more land-use conflict as animals routinely cross the northern border into Montana in search of wintering habitat. There, the bison compete with livestock for forage and risk causing the state to lose its brucellosis-free status.

So what are bison advocates to do? To maintain a healthy herd, one of two things must happen: habitat must be increased or bison numbers reduced. Bison lovers want increased habitat, but nearby ranchers see bison as a liability. The current bison management plan attempts to resolve this issue through hazing, capture, quarantine, and slaughter. All have been controversial and costly.

The problem of wildlife threatening the livelihoods of nearby ranchers is certainly not new to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Many of the same conflicts arose during the reintroduction of wolves in the mid-1990s. Ranchers viewed wolves as a threat to their livestock and aggressively opposed the plan—that is, until an entrepreneurial environmental group stepped in.

Defenders of Wildlife created a compensation program that reduced ranchers’ liability of wolf reintroduction. The program, funded by supporters of the reintroduction plan, has paid out more than $1.4 million to livestock owners and helped wolf lovers realize the costs of reintroduction and ranchers realize the value of wolves.

Creating such a program for bison habitat has historically been difficult. If a wayward bison transmitted brucellosis to nearby cattle, federal regulations required that the entire livestock herd be killed. Compensation for such a loss would be largely unpredictable and cost prohibitive.

However, under the revised national brucellosis regulations, only the infected livestock are required to be slaughtered—not the entire herd. In addition, states will no longer automatically lose their brucellosis-free status if the disease appears in two or more herds during a two-year period. These new rules could enable environmental groups to follow the lead of wolf advocates and compensate landowners for their losses due to bison.

Striking agreements with landowners is not entirely new for bison advocates. In 2008, an agreement was reached with a large landholder to protect bison habitat outside the park. Environmental groups, along with state and federal agencies, purchased a 30-year lease along a narrow corridor of the Yellowstone River north of the park. There have also been efforts afoot to retire grazing permits on public lands adjacent to the park. Incorporating similar programs that compensate landowners for accommodating bison has the potential to promote cooperation where historically there has only been hostility.

As was the case with wolves, the rancher-bison conflict will remain as long as bison are seen as a liability instead of an asset by those who own potential habitat. If ranchers and other land users can realize a benefit from bison, rather than bear the brunt of the burden, they will be more willing to provide forage and land for them. Finding out how to reach an agreement, even in the absence of the lengthy and costly political process, is the key to letting the buffalo roam.