Economic research has long been subject to a pitfall: it lacks a laboratory in which to carry out simple experiments. Unlike sciences such as physics or chemistry, economic data are messy, imperfectly measured, and affected by any number of unknown variables. This makes it difficult to understand how humans and markets actually work.

The field of experimental economics attempts to address these challenges. Using controlled laboratory experiments and computer programs, researchers are able to take a more scientific approach to understand human behavior, and they are often uncovering new revelations about the way human societies work. Long-time friend of PERC and former board member Vernon Smith won the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics for his experimental economics research, which sought to go beyond mathematical abstractions and understand the role human institutions play in creating social rules and order.

Bart Wilson is a colleague and coauthor of Vernon Smith at the Economic Science Institute at Chapman University and a 2013 PERC Lone Mountain Fellow. This week, Bart visited PERC to explore how societies form rules and order. He even tested a laboratory experiment on the PERC staff to further demonstrate how human institutions emerge and how those institutions respond to sudden and dramatic changes. The experiment reveals something about how societies avoid collapse.

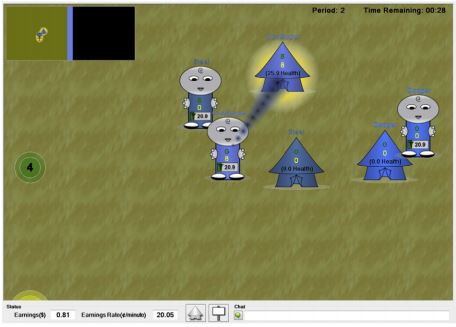

Here’s how it worked: Each PERC participant was provided a laptop and given instructions on how to navigate a virtual world resembling early human agricultural settlements. Players must harvest renewable resources—either green or yellow patches—to maintain a health rating. Each colored patch has a numerical value. The more health earned throughout the game, the more reward paid at the end of the experiment. The game is divided into “weeks” in which players can harvest and consume one resource per week.

Consuming the patches, however, has one caveat: Your health is improved if you consume an equal value of each color—for example, 6 green units and 6 yellow units. But because players can only consume one patch each period, they must learn to cooperate with each other to consume equal amounts of both colors in each period. To do so, players learn to trade units to other players.

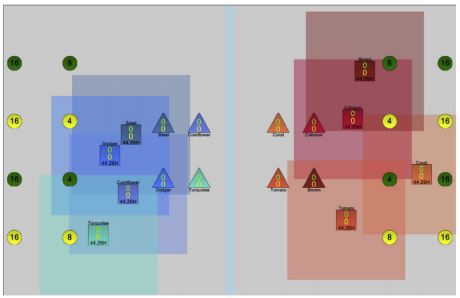

Not only must players learn to cooperate throughout the experiment, they must also face the consequences of an ecological shock. Partway through the game, an unexpected drought hits the resources for one subset of the players. Doing so allows the researchers to understand how the newly created institution of trading is affected by the shock. In addition to the shock, strangers begin to appear on players’ screen. Unknown to the participants, the players were initially divided into two worlds, where they established separate informal institutions for harvesting their resources. Now, because of the drought, they are forced to interact in their search for available resources.

By running multiple experiments of this sort, Bart and his colleague Erik Kimbrough find that whether societies collapse depends on the extent to which they cooperate and trade with each other, and this cooperation is highly dependent upon local circumstances. However, once the informal institutions for cooperation emerge within a group, cooperation between separate groups becomes difficult. When the two isolated groups are allowed to interact during a time of resource scarcity, the “other” group is treated with suspicion and a lack of cooperation.

The experiment, published recently in the journal Ecological Economics, reveals how sensitive institutional adaptation is to its social and ecological context. “Not only are informal rules of property and exchange path-dependent, but they are also particularly fragile when stressed by the sentiments of tribal solidarity that impulsively surface in the face of ecological distress,” the authors write. “Whether collective action in response to socio-ecological change is fraught with conflict or leads to new forms of cooperation may depend crucially on the context in which it arises.” It’s a reminder that our deeply rooted and context-specific human institutions must be able to adapt in an ever-changing world.

For more on Bart’s work, check out his PERC Q&A from 2011 on experimental economics and property rights.