Testimony provided to the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources hearing on “Funding the National Park System for the Next Century,” July 25, 2013.

1. Main points:

- Local managers know better than Congress how to address their maintenance and operational needs.

- Overreliance on congressional appropriations contributes to maintenance backlogs and causes park managers to respond to political forces rather than park users.

- Congress should continue to allow the National Park Service to charge recreation fees and retain most of the revenue onsite to reinvest in infrastructure and operations.

- The federal government should stop acquiring new land and use revenues from the Land and Water Conservation Fund for the maintenance and operation of existing federal lands.

- Congress should look to state parks for innovative management strategies such as public-private partnerships that can improve park operations and reduce funding needs.

2. Introduction:

Thank you, Chairman Wyden, Ranking Member Murkowski, and members of the committee, for the opportunity to provide testimony today on how to address the National Park Service’s backlog of deferred maintenance and operational needs. As the agency prepares to celebrate its centennial in 2016, creative solutions and responsible policies are needed to address the challenges of running parks in the twenty-first century.

In short, I will argue today that local park managers know better than Congress how to address their maintenance and operational needs. Congress should give the National Park Service broad discretion in how it allocates its appropriations and revenues. When funding is appropriated by Congress for specific projects, it reduces the ability of local park managers to address local park needs. Second, an overreliance on congressional appropriations can cause park managers to cater more to the demands of politicians than to the ongoing maintenance needs in their parks. Congress should continue to explore alternative funding strategies that reduce parks’ reliance on general appropriations.

I submit this testimony based on my experience from a number of perspectives. First, I am a research fellow at the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), a nonprofit institute dedicated to promoting market solutions to environmental problems. For more than 30 years, PERC has advanced public land management strategies that link fiscal responsibility with environmental stewardship. From our research into public land policy, we understand that when land managers are forced to respond to distant policymakers rather than park users, park management suffers.

Second, I am a former backcountry ranger for the National Park Service. My experience in the Park Service gave me a deeper appreciation for the challenges facing park managers and the extent to which deferred maintenance projects can negatively impact park resources. The backlog of road repairs, wastewater treatment, facility upgrades, and other critical infrastructure projects affects the quality of visitor experience as well as parks’ natural and cultural resources. In addition, I had a first-hand look at how political forces can distract from park managers’ ability to effectively run parks.

Third, I am a frequent park visitor. As a resident of Bozeman, Montana, I regularly hike and climb inside national parks. I care for their future and want to see their beauty protected for future generations. At the same time, I witness how the decisions made far away in Washington D.C. can impact local park managers, neighboring communities, and our national treasures.

Given these perspectives, I will argue today that Congress should consider the following proposals to address its critical infrastructure needs. First, Congress should reauthorize the Federal Land Recreation Enhancement Act, which allows federal agencies, including the National Park Service, to retain their recreation fees for use within the agencies. Second, Congress should divert funding for federal land acquisition to address the backlog of maintenance and operational needs on existing federal lands. Third, policymakers should look closely at how state parks have addressed similar funding challenges through the use of innovative public-private partnerships.

3. Reauthorize the Federal Land Recreation Enhancement Act

No one understands the maintenance and operational needs of parks better than park managers themselves. Congress should continue to allow federal land agencies to charge recreation fees and retain most of the revenue on site to reinvest in park infrastructure and enhanced recreation services as identified by local park managers. To this end, Congress should reauthorize the Federal Land Recreation Enhancement Act (FLREA). The FLREA is a positive step towards encouraging park managers to respond to visitor demands rather than the whims of distant politicians.

Recreation fees have been an important feature of parks since the creation of the National Park Service (NPS) in 1916. However, for much of the agency’s history, the fees collected at parks have been funneled back to the national treasury. Each year, parks relied on Congress to re-appropriate the revenue back to the agency. Often these appropriations were spent on politically determined projects rather than on important repairs and renovations. Over the years, Congress continually neglected maintenance projects in its park appropriations. In addition, because fee revenues went directly to the treasury, parks had little incentive to invest in fee collection.

Reliance on congressional appropriations has created an enormous backlog of deferred maintenance needs, which the NPS now estimates at $12 billion. These unmet needs include road repairs, wastewater treatment, and facility upgrades, among other critical infrastructure projects. To name just a few examples, at least $15 million is needed to replace water and wastewater facilities at Yellowstone National Park, and more than $16 million is need to ensure safe drinking water is available at Grand Canyon National Park.[1] Such unfunded maintenance needs adversely impact visitor experience and resource protection.

Today, the FLREA allows the National Park Service to retain the fees collected at parks without separate appropriation from Congress. The program began in 1996 as the Fee Demonstration Program and was extended in 2004 as the FLREA. The Act authorizes 80% of the fees collected by parks to be reinvested at the unit in which the fees were collected. Revenues from the FLREA can be used for deferred maintenance, interpretation, law enforcement, and fee collection.

The FLREA helps address a number of issues: First, it helps fill gaps in congressional appropriations. In the wake of federal sequestration and other budget cutting measures, these gaps are likely to increase. Second, unlike most congressional appropriations, the revenues collected from the FLREA are often used to address critical maintenance needs. In recent years, park managers have allocated more FLREA funding to deferred maintenance and facility improvement than other project types. The NPS funded more than 1,300 projects through the FLREA in fiscal year 2012, about half of which addressed deferred maintenance and facility needs.[2] Finally, the Act encourages park managers to rely on park users for a portion of their funding, which gives them the right incentives to provide visitors with enhanced recreational opportunities.

Congress should do more than just reauthorize the FLREA, which is set to expire in December 2014. It should encourage parks to become more autonomous by allowing them to charge more creative and realistic recreation fees. Modest changes to park fees are unlikely to have a significant effect on park visitors, but could generate much-needed revenue to cover the costs of park maintenance. Studies at Yellowstone and Yosemite national parks show that entrance fees made up just 1.2 percent and 1.5 percent of visitors’ overall trip expenditures, respectively.[3]

A recent report by the National Park Hospitality Association and National Parks Conservation Association discusses many potential revenue-enhancing fee adjustments, including:

- Increasing the price of the one-time senior lifetime pass from $10 to $80. Alternatively, the report recommends retaining the $10 senior pass price, but making it an annual rather than lifetime pass.

- Changing most fees to per-person rather than per-carload rates.

- Changing most entrance fees to a daily fee rather than a week-long fee.

- Differential pricing to encourage visitation during non-peak periods, both weekly and seasonally.

- Fee waivers for those whose ability to pay is limited.[4]

Recreation fees alone will not solve the NPS’s budgetary problems—fee revenue represents about 10% of the agency’s total budget. But if parks are able to freely use the funds they generate, fees represent an important strategy to improve visitor services, maintain and enhance park resources, and reduce project backlogs.

4. Reform the Land and Water Conservation Fund:

The National Park Service backlog is made worse by the continued acquisition of federal lands. Congress should divert funding for land acquisition to address the unfunded maintenance and operational needs on the land the government already owns.

The Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) is the federal government’s primary means of acquiring land. The fund is authorized at $900 million each year for land acquisition, with most of the revenue derived from offshore oil and gas leasing. The LWCF is appropriated annually by Congress and split between a state-level matching grant program and a federal land acquisition program. The federal portion of the fund is limited to land acquisition and is not authorized to be used for the maintenance and operational needs on current federal lands. In short, the fund allows the government to purchase more land, but does not provide for the care and maintenance of existing land.

The LWCF is set to expire in 2015 and represents a significant opportunity for Congress to address the management needs on the lands already under federal ownership, including national parks. Congress should amend the LWCF to require funds for the federal program to be used for the maintenance and operation of existing federal lands. The amount of funding that could be derived from the LWCF for these purposes is substantial. From 1985 to 2010, the fund allocated $6.6 billion for federal land acquisition. Instead of using these funds to address its maintenance needs, the government acquired millions of additional acres. These additional lands only contribute to the burden of backlogged park projects.

The federal government currently owns 635 million acres, or roughly three out of every 10 acres in the United States. Much of this federal ownership is concentrated in the West, where roughly half of the land is federally owned. The National Park Service manages 80 million acres, or 13 percent of all federal lands.[5] Given the size of the federal estate, and the extent of the management needs on those lands, spending millions each year through the LWCF acquiring news lands is irresponsible. Amending the LWCF to require funds to be spent on existing federal lands can supplement fee revenue to address the NPS maintenance backlog. These LWCF funds, however, should be made available for park managers to use in ways that best address their individual park needs rather than earmarked for specific projects or purposes.

5. Innovative Funding Options from State Park Management

Congress should also look to state parks for innovative management strategies. State parks receive 700 million visits each year, more than twice as many visits as the National Park Service but on less than 20 percent of the acreage. Similar to the NPS, most state parks rely on appropriations and user fees for funding. When state budgets are tight, state parks are among the first to be cut. To address these funding challenges, some states have entered into creative public-private partnerships that improve visitor service, reduce management costs, and keep parks open, often with no reliance on government appropriations. Congress should explore similar partnerships for national park management.

Consider, for example, Arizona’s state park system. Facing massive budget cuts, the state cut appropriations for Arizona State Parks to zero in 2010. Deferred maintenance needs totaled more than $200 million. Drinking and wastewater systems were not up to code and the integrity of park infrastructure was in question. “Arizona Parks are crumbling before our eyes,” according to a park task force. “The entire system is on the verge of collapse.”[6] The state was forced to close 13 parks.

Public-private recreation partnerships have demonstrated the ability to address many of these challenges, all with little or no change in the underlying services and recreation opportunities provided by the parks.[7] State agencies contract with private firms to provide the operational services for parks under strict guidelines and requirements. Often the agreements are for whole-park operations, rather than traditional in-park concessions such as stores, marinas, and bike rentals. Under these whole-park private leases, the public agency maintains control and ownership of the unit and defines the specific goals of park management. The private lessee is responsible for operational tasks, such as visitor services, fee collection, maintenance, cleaning, and some infrastructure maintenance.

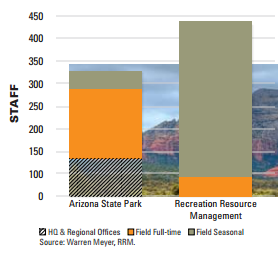

One such private park operator, Recreation Resource Management (RRM), illustrates the success of this approach. In 2010, RRM offered to lease six state parks from Arizona State Parks after the agency threatened to close them. The company pays an annual lease, or rental fee, and a percentage of the total fees earned. All operational expenses are covered by user fees, meaning that no appropriations from the state are required. Today, RRM operates more than 175 sites in 11 states (state parks, U.S. Forest Service campgrounds, and other recreation sites), including 35 recreation sites in Arizona.

Figure 1: Arizona State Parks and RRM Employees

Unlike most public park management, private park managers would be out of business without visitors. As a result, RRM has an incentive to attract visitors and provide high-quality, cost-effective recreational opportunities. In addition to earning a profit, the company often generates revenue back to the state agency by reducing management costs and assembling a more flexible labor force. Visitor comments are generally positive and many are simply unaware that park operations are run by private company. The company has invested in maintaining and replacing infrastructure to improve the park experience. These include installing new composting toilets, showers, and visitor center renovations.

Congress should encourage similar public-private partnerships for national parks. Contrary to one common misconception, such partnerships with private companies will not result in the construction of a McDonalds next to Old Faithful or luxury condos overlooking the Grand Canyon. Under the terms of the operating contract, private park operators cannot change fees, facilities, or impact the natural resources within a park without the approval of the public agency. Private park operators must manage within public agency’s mission. While the NPS currently uses private concessionaires for many in-park operations, Congress should encourage more public-private partnerships for national park management across the agency, building on the success of companies like Recreation Resource Management.

As Warren Meyer, president of RRM, recently stated: “The objective is to form a partnership combining the public oversight and unique environmental knowledge of the state park agency with the efficiency and customer service of a private company that can clean and maintain the parks without the need for a taxpayer subsidy.”[8] If this model were replicated for national parks, it would address ongoing funding concerns, help alleviate deferred maintenance and operational needs, and improve overall park management.

6. Conclusion

As the National Park Service enters its second century, a host of challenges lie ahead. The agency will be unable to address those challenges with the burden of a $12 billion backlog in deferred maintenance and operational needs. This week, the House of Representatives proposed legislation containing $2.3 billion for the National Park Service, a decrease of 9% from the enacted level in fiscal year 2013. Clearly, general appropriations cannot address the magnitude of the agency’s unmet needs. Creative solutions are needed.

In this testimony, I have outlined three proposals Congress should consider: extending and strengthening the Federal Land Recreation Enhancement Act, reforming the Land and Water Conservation Fund, and exploring innovative public-private partnerships for national park operations. These reforms will reduce the agency’s reliance on general appropriations, improve the maintenance and operations on existing lands, and prepare our parks for the challenges of the twenty-first century. Thank you for taking up this important issue and for giving me the opportunity to testify today.

7. Biography

Shawn Regan is a research fellow at the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) in Bozeman, Montana. PERC is a nonprofit institute dedicated to improving environmental quality through property rights and markets. He is a former backcountry ranger for the National Park Service. He holds a M.S. in Applied Economics from Montana State University and degrees in environmental science and economics from Berry College. His research and writing have appeared in Regulation, High Country News, Quartz, and newspapers across the country.

[1] National Parks Conservation Association. 2011. Made in America: Investing in National Parks for Our Heritage and Our Economy. 14

[2] National Park Service. Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2014. Rec Fee-2 – Rec Fee-3.

[3] Duffield, J., D. Patterson, C. Neher, and N. Chambers. 2000. Evaluation of the National Park Service Fee Demonstration Program: 1998 Visitor Survey. Report prepared by the University of Montana in conjunction with the National Park Service.

[4] National Park Hospitality Association and National Parks Conservation Association. 2013. Sustainable Supplementary Funding for America’s National Parks: Ideas for Parks Community Discussion. March 19.

[5] Congressional Research Service. 2012. Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data. February 8.

[6] Governor’s Task Force. 2009. Governor Brewer’s Task Force on Sustainable State Parks Funding. Phoenix, AZ: Arizona State Parks.

[7] Fretwell, Holly L. 2011. Funding Parks: Political versus Private Choices. PERC Case Studies. Available at: https://www.perc.org/articles/funding-parks-political-versus-private-choices

[8] Meyer, Warren. 2011. A Successful Model for Keeping Arizona’s State Parks Open Exists… Right Here in Arizona. May 3. Available at http://parkprivatization.com/2011/05/press-release-a-successful-model-for-keeping-arizona-state-parks-open-exists-right-here-in-arizona/