Editor’s Preface

Canada’s First Nation land tenure system was designed in the mid-nineteenth century. It was meant as a temporary measure: Indians would be placed on reserves until they were sufficiently acculturated to hold property in their own right, live independently of government supervision and protection, obtain the right to vote, and become subject to taxation. Reserves were isolated geographically and legally from the rest of society and were expected to disappear over time as the Indian population entered the surrounding world.

Much like Indian reservations in the United States, Indians were to be granted property rights only when they decided to leave their former way of life and enter “white” society. Until they did so, they would have to live under the land tenure system of Canada’s Indian Act, where the land they lived on was owned by the government. The idea behind this land tenure system was not to incentivize economic activity by the Indian population; quite the contrary. It was intended to incentivize leaving the reserves and the Indian way of life in order to gain the possibility of a “normal” economic and political life.

History has not accorded with this view. Yet, the land tenure system of the Indian Act continues to exist and to frustrate the economic aspirations of First Nations in Canada.

Reserve land under the Indian Act is Crown land, the legal title to which is held by the government for the use and benefit of an Indian band. Because the land is held by the Crown, a trust or fiduciary responsibility lies with the government regarding its management of the land. The land itself is inalienable and cannot be sold or mortgaged unless the Indian interest in it is yielded by the band to the government. As far as Indians are concerned, they can only hold a right of “possession” of a parcel of reserve land, which can only be sold or passed on to other members of the band. To lease reserve land to a non-band member requires the approval of the government.

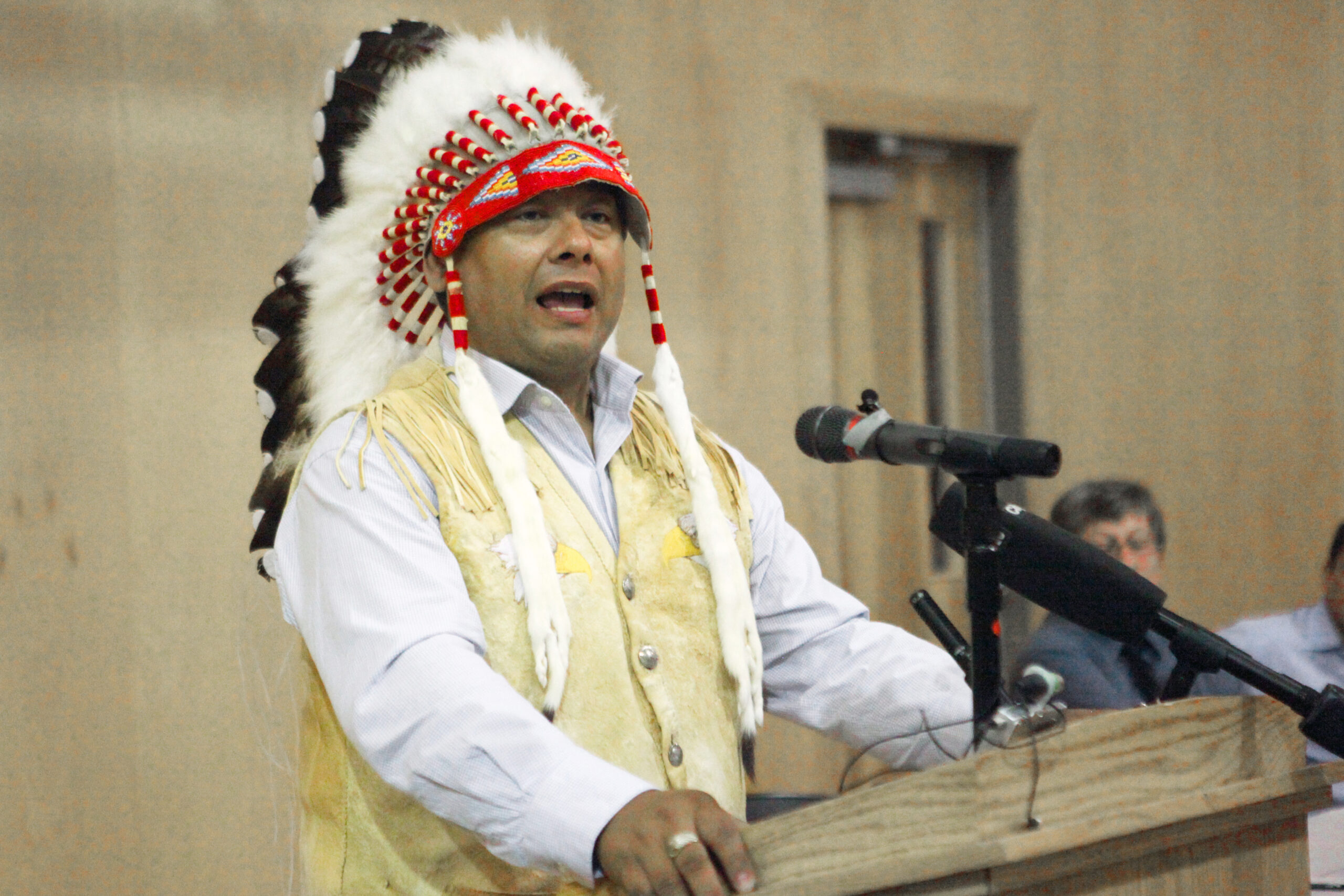

The First Nations Property Ownership (FNPO) initiative has been underway in Canada since 2006. The initiative is led by the First Nations Tax Commission, under the leadership of Chief Commissioner Clarence T. (Manny) Jules.

Overview of First Nations Property Ownership Initiative

- First Nations should have the option to hold the legal title to their existing reserve land.

- Individual First Nations should have the power to transfer the full legal title to individuals, while retaining their jurisdiction over the land despite any possible change in ownership.

- First Nation jurisdiction over their reserve land should be substantially expanded.

- Safeguards should be included to preserve the First Nation character of the land.

Who Should Own Our Lands?

It has been over 100 years but, to this day, Tk’emlups te Secwepemc home and native land remains “a tract of land… whose legal title is held by her Majesty.” We don’t own our land in the eyes of Canadian law and, consequently, we find ourselves with justice withheld and no real home.

Our former leaders believed we should own our land. Our community members today believe we should own our own land. I believe we should own our own land. This is why our community, along with other First Nations, is advocating for the First Nation Property Ownership legislation. This legislation would return Tk’emlups land to the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc. And when it does, we, and not the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, will make the decisions pertaining to our land.

We believe that taking back title to our land is the key to justice and the path out of dependency. FNPO will not only create real Tk’emlups land, but it will provide the Tk’emlups Nation with permanent legally recognized jurisdiction over this land. In short, it means we will govern our land and the people living on it, and we will be able to enjoy the same property rights that all other Canadians enjoy.

In the Shuswap Memorial our leaders said of the newcomers, “we shall help each other to be great and good.” They meant it then and we mean it now.

Our community has been an important part of the local economy for decades. We started one of the first industrial parks on First Nation lands in British Columbia in the 1960s. Today, our lands generate thousands of employment opportunities for our members and non-members alike. Our economy contributes millions of dollars to the regional economy and supports the tax base of every order of government. Our people have never been idle and we resent the assertion that we have been, that we don’t contribute, or that we are incapable of managing our own affairs.

We believe that taking back title to our land is the key to justice and the path out of dependency. FNPO will not only create real Tk’emlups land, but it will provide the Tk’emlups Nation with permanent legally recognized jurisdiction over this land.

Yet, we could do so much more. And this does not require special rights. We just need what other Canadians take for granted: the right to own our homes, access to a mortgage or a business start-up loan, the ability to bequeath our assets to the next generation, and the capacity to resolve disputes related to estates and marital breakdown with marketable assets.

Our poverty isn’t because of culture or race. We are as entrepreneurial and innovative as other Canadians yet we have lower incomes, more dependency on welfare, and higher incarceration rates than other Canadians.

Our problems are solvable. We lack the laws and legal framework that support markets, reduce the costs of doing business, and provide individuals with economic opportunities. We lack land registry, title, and surveying systems that provide certainty and security to lenders and investors. We lack the revenues to build infrastructure and implement our laws. All of these deficiencies can be addressed with a stroke of a pen through the passage of the FNPO legislation.

In 2013 in Canada, only the mentally incompetent, children, and First Nation people on reserve are not allowed to own land. Property ownership is a basic human right. We cannot continue our work of making all the people on our traditional territory “great and good” until our right to property ownership is restored. We should own our own land.

For more information on FNPO, visit: fnpo.ca/proposal.aspx