Judging by the headlines and court cases, it is practically impossible to transfer water in California without first wading through years of red tape and litigation. Issues related to endangered species, conveyance, and third-party impacts preclude all but the largest and most profitable agriculture-to-municipal transfers. Or so it seems.

Without much fuss or fanfare, the Scott River Water Trust in Siskiyou County has pioneered the use of low-volume, low-cost water leases to enhance environmental flows. The trust pays farmers along the Scott River and its tributaries to leave water instream for salmon and steelhead, particularly during periods of drought and low flows.

The success of the Scott River Water Trust can be replicated throughout California, despite all of the red tape entangling instream flow transfers. This case also demonstrates how water markets can facilitate both economic growth and municipal development while also enhancing environmental flows and strengthening agricultural communities.

Use It or Lose It

Unlike eastern states, where riparian landowners have a coequal right to the reasonable use of water flowing by their property, the laws of most western states require users to divert water from a river or stream and put it to a beneficial use to maintain a water right. If a right holder does not divert the full amount to which she is entitled, a downstream user can take that water and, after a number of years of non-use, claim that the upstream user forfeited the right.

This “use it or lose it” principle is fundamental to the prior appropriation doctrine, but it compels right holders to divert water out of stream even when they don’t need it—just to maintain the water right.

California’s water code contains this use it or lose it provision and, unlike every other western state, also recognizes water rights for riparian landowners. With these compounding demands on California’s water, many rivers and streams are oversubscribed and dewatered, particularly during dry seasons and drought years.

Swimming Upstream Without Water

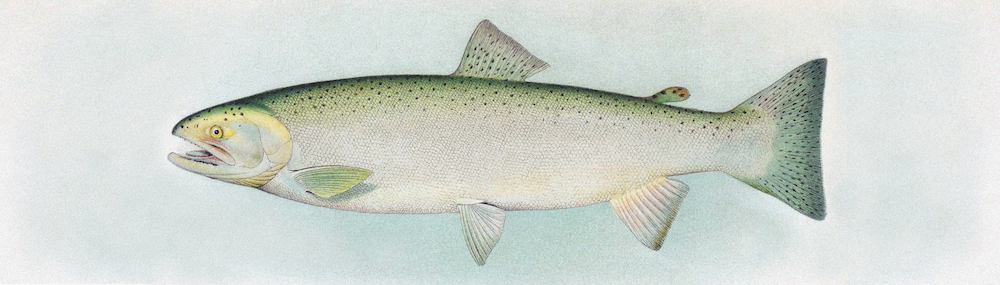

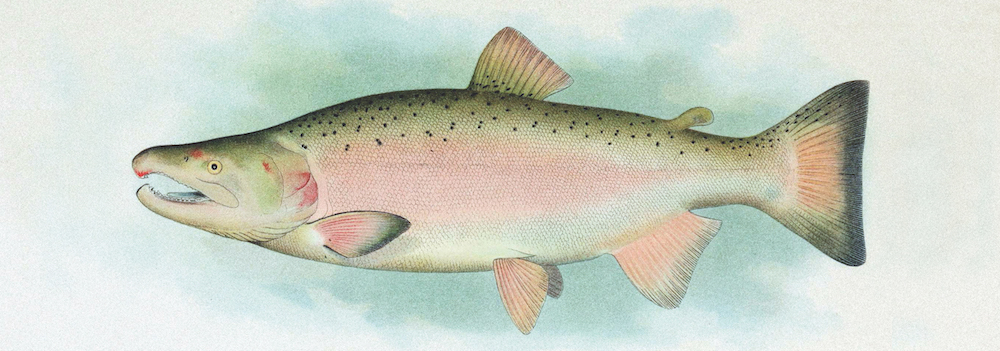

Seasonal dewatering has hammered salmon populations along California’s coast, but the collapse of the Central Valley’s fall run Chinook population is perhaps the most striking. Historically, up to two million of these fish returned annually to spawn in the Sacramento and San Joaquin river system. But in 2007, the Pacific Fishery Management Council recorded only 91,000.

The coast-wide trend prompted the council to completely shut down the 2008 and 2009 commercial salmon fishing seasons, costing California’s economy approximately $255 million annually. Despite the closures, the spawning numbers continued to fall, eventually bottoming out in 2009 at a paltry 41,000 fish.

The dewatering of spawning rivers and streams is not the only reason salmon numbers have declined along the Pacific coast. Dams block the fishes’ upstream travel, ocean currents impact food availability, harvesting rates can exceed sustainable numbers, and in central California two massive pumping stations in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta alter river flows and impair salmon migration.

Dewatering, however, is singularly important for salmon because the adults return to spawn in the river in which they were born, often to the exact area of their birth. Coho salmon and steelhead young must spend one or two years rearing in freshwater, including the low-flow periods of summer and early fall, before migrating to the ocean. If flows in that river become too low, their numbers can plummet. The question is how to get more water instream for the fish during critical periods of their life cycle.

Lease, Don’t Litigate

Not surprisingly, given that several salmon and steelhead populations are listed as threatened or endangered, environmental groups use litigation to try to reallocate water from farmers to fish. These lawsuits claim that the state and federal protections trump the property rights of water users. To date, the litigation has done more to breed acrimony and distrust between neighbors than to actually increase stream flows. The problem is that litigation is a time-consuming and zero-sum game wherein one side gains only if the other side loses.

But a different approach has gained traction in the Scott River Valley of northern California’s Klamath Basin. There, seasonal dewatering occurs along reaches where steelhead trout, coho salmon, and Chinook salmon spawn, but rather than litigate, the environmental and agricultural interests are negotiating mutually-beneficial agreements to share the water.

The Scott River Water Trust is a non-profit organization that negotiates voluntary agreements with water right holders to leave water instream. The trust pays farmers not to divert water during specified low-flow periods, typically 30 to 90 days, after which the farmers can once again use their water for irrigation and/or stockwater.

Unlike with outright purchases, the trust never acquires an ownership interest in the water, allowing it to bypass the complicated and time-consuming regulatory review process. Instead, ownership remains with the farmer, and no one other than the trust and water user are involved in this relatively simple transaction.

Another option is the more formal process of changing a water right under the California Water Code section 1707. In this case, the farmer changes his or her water right with the State’s Division of Water Rights to reflect the temporary or permanent use change to environmental flows. A high level of scrutiny is involved in this 1707 review process, which can be lengthy and expensive regardless of the volume of water left instream. In testing each option, the Scott River Water Trust has learned several valuable lessons about negotiating for water with members of an agricultural community.

Community Negotiation

The mission of the Scott River Water Trust is to improve instream flows for salmon and steelhead while protecting the local family farms. What’s interesting is how these two goals have proven to be both complementary and contradictory. They have proven complementary in the sense that, by paying farmers to leave water instream, the trust is adding to the farmers’ bottom line. Because the agreements are totally voluntary, presumably the farmers don’t sign on unless doing so makes economic sense. And while the payments might not cover the full cost of leaving the water instream, receiving a check from the Scott River Water Trust is far better than having to pay attorneys to defend the water right in litigation.

The two goals of supporting the community and increasing stream flows proved to be somewhat contradictory when the trust first began negotiating the terms of forbearance agreements with each farm. Some farmers were willing to accept a lower price than others, and when the word got out that some deals were better than others—an inevitability in a small agricultural community—the deals became a source of discord.

In addition, non-participating farmers have occasionally diverted water that their upstream neighbors left instream for the fish. This action is perfectly legal if the water was left instream pursuant to a lease (as opposed to an outright purchase) and the water right is a lower priority. This outcome, however, obviously undermined the trust’s effectiveness.

The solution was for the Scott River Water Trust to develop a more sophisticated pricing structure. First, the trust decided to offer a flat price per acre-foot, one that varies by the water year conditions (wet, average, dry, or critically dry) but is otherwise fixed and non-negotiable. The second change the trust instituted was to offer bonuses for neighbors who enrolled collectively. This created an incentive for water to be left instream for longer stretches of river, rather than just from one headgate to the next.

Buy That Fish a Drink

The results have been impressive. Summer leases during the first three years of operation added approximately 279 to 330 acre-feet of water to priority streams, improving 3.7 to 6.1 miles of instream rearing habitat. Fall leases during the same time period accounted for an additional 280 to 481 acre-feet added to the Scott River’s mainstem, benefitting up to 53 miles of spawning habitat. Not surprisingly, the salmon numbers responded. In 2008, there were a measly 62 adult coho salmon documented in the Scott River watershed. This number increased more than five-fold by 2011 when the return totaled 340.

In addition to the environmental benefits, the trust has helped build a sense of cooperation in the community. Scott Valley rancher Jim Morris said, “We value the water for livestock as well as for groundwater recharge. We care about the fish and we’re glad that the water trust allows us to help meet the salmon’s water needs during an emergency situation.” In critically dry 2013, the trust accomplished nine summer leases on four streams adding 477 acre-feet to benefit 11.9 miles of habitat and has added at least 800 acre-feet to the Scott River during the fall spawning runs. And during an extreme drought in 2014, the water trust played an instrumental role in a rescue and relocation effort to save spawning fish. Scott River Water Trust staff worked to forge 12 leases with farmers and ranchers, which kept 766 acre-feet instream and improved habitat along 16.5 miles of the river.

The water trust tested one relatively simple, small instream dedication through the state’s 1707 process, but it took two years and $30,000 to obtain. As a result, its board of directors is seeking a more streamlined process with the state before embarking on any further dedications. The temporary forbearance agreement option continues to be its primary tool.

Catching Up in California

In 1991, the California legislature amended the water code to permit the use of water rights for the purpose of preserving or enhancing wetland habitat, fish and wildlife resources, and recreation. It was this change that relaxed the “use it or lose it” rule and allowed users to leave water instream without forfeiting their appropriative water rights. Nonetheless, the number of changes and transfers to instream flows has been lower in California than in other western states, particularly when excluding leases by state and federal agencies.

One reason so few rights have been changed to instream flow is the state’s burdensome review process. Petitioners must demonstrate that any proposed change won’t harm other legal water users, including riparian landowners whose rights are not specified in volumetric terms unless an adjudication has occurred. In addition, when a proposed change would result in an export of water out of county, petitioners must demonstrate that the change will not unreasonably affect the overall economy of the exporting county. These requirements add significant cost to the transfer process, often in the tens of thousands of dollars, and reduce the number of water right changes to instream flows.

One way for Californians to avoid the courtroom controversies that pit economic productivity against endangered species is to streamline the administrative review process for instream flow transfers. The success of the Scott River Water Trust demonstrates that price incentives and negotiation works better than litigation at balancing competing water demands. But more could be accomplished in the Scott River Valley and elsewhere in the state if the instream dedication process was made easier.