Americans have unrivaled opportunities to hike, hunt, fish, and camp on millions of acres of public lands. In total, more than one-third of the nation is open to many or all of these uses through federal and state land ownership. The public’s ability to access these lands represents an important component of the American model of conservation.

But America’s portfolio of public land assets is at risk. Increasingly large numbers of outdoor recreationists are becoming “free riders” that bear little or no cost for public land management. As a result, traditional sources of funding are falling behind the needs of public land agencies to continue providing outdoor recreation opportunities.

Public access to these lands is the legacy of a complex history based, in part, on an understanding among hunters and anglers that the privilege of public access entails the responsibility of paying to play. Yet today, most recreationists have little appreciation for how public lands are funded—assuming it’s their tax dollars at work, or that their preferred form of recreation doesn’t cost anything to provide.

The reality is that our public lands need funding. As land management budgets diminish and outdoor demographics shift, America’s model for funding conservation needs to adapt.

PUBLIC LAND FUNDING HAS HISTORICALLY been provided through a mix of congressionally appropriated tax dollars, state tax dollars, license fees, excise taxes, and special-use permits. Today, these traditional funding sources are in decline.

Consider state natural resource departments. Historically, about 90 percent of state fish and wildlife budgets were derived from hunters and anglers. These were primarily generated from sales of hunting and fishing licenses, as well as excise taxes on guns, ammunition, and fishing gear. The rest was made up of general fund appropriations, sales taxes, lotteries, and other sources on a state-by-state basis.

But this funding model faces many challenges today. Over the last several decades, the number of licensed hunters and anglers has declined as a share of the overall population. In 2011, only 16 percent of Americans hunted or fished, down from 27 percent in 1975.

There is also a growing need for proactive forms of public land management arising from new types of recreation and environmental challenges such as endangered species and climate change. Without new revenue sources, less funding will inevitably translate into diminished land health and fewer recreational opportunities.

The story is much the same for the federal government. The National Park Service, Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Fish and Wildlife Service—which together manage 28 percent of the United States—face billions of dollars in deferred maintenance projects, yet budgets are flat-lined and staffing levels are in decline. In the meantime, routine maintenance, restoration, and enhancement projects go unmet.

AT THE CORE OF AMERICA’S CONSERVATION model is the concept of “user pays, user benefits.” The idea is simple: If sportsmen want to fish or hunt, they have a responsibility to fund the management and conservation of fish and wildlife. This has been accomplished primarily through license sales and self-imposed excise taxes.

The “user pays, user benefits” concept traces its history to two pieces of landmark legislation in the 1930s: the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, known as the Duck Stamp Act, and the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, known as the Pittman-Robertson Act. These federal statutes established special funds to be used exclusively for wildlife conservation—and paid for by the very same users who benefit from it.

The Duck Stamp Act authorizes the sale of federal bird hunting stamps, which are required to hunt waterfowl in the United States. Since 1934, these duck stamp sales have generated more than $725 million for the conservation of wetlands and other bird habitat, resulting in more than five million acres of protected habitat.

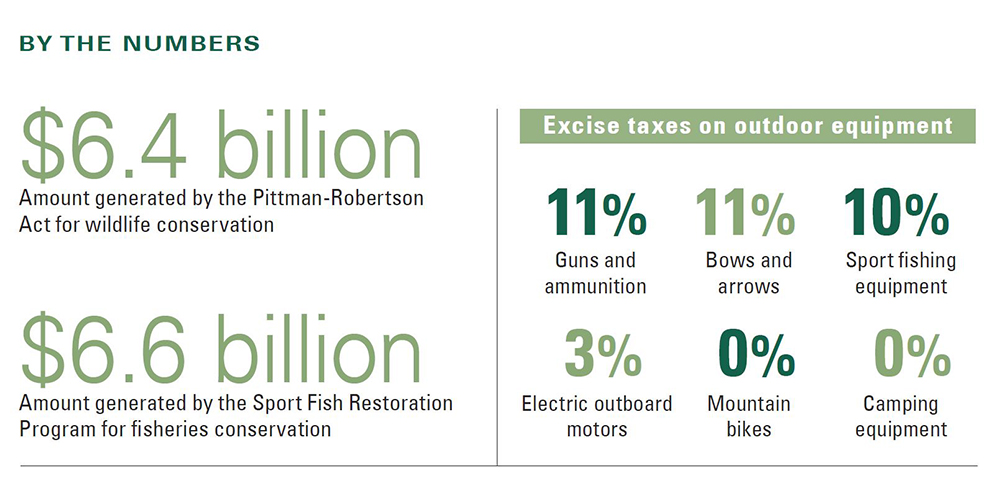

The Pittman-Robertson Act provides funding for wildlife habitat, research, and education through an excise tax imposed on sporting arms, ammunition, archery equipment, and handguns. Funds are apportioned back to states based on their size and the number of paid hunting license holders. The funds support up to 75 percent of the cost of a project, with states providing a 25 percent match—typically funded with hunting license fees. Between 1930 and 2010, Pittman-Robertson funds provided $6.4 billion for wildlife conservation.

Building on the success of these “user pays, user benefits” programs, the Sport Fish Restoration Program was created in 1950 for fisheries conservation. Much like Pittman-Robertson, the program levies an excise tax on select fishing equipment and boat fuels. From 1952 to 2010, the program distributed $6.6 billion back to the states for a wide variety of habitat improvement, access, research, and education projects.

These “user pays, user benefits” programs are perhaps more accurately called “user pays, public benefits” programs. Their benefits extend far beyond the individual sportsmen to the public overall in the form of habitat acquisition and restoration, species restoration, public access, as well as education and research. Taken together, no other set of conservation efforts can claim a greater financial contribution to fish and wildlife conservation than these three programs.

MANY OF TODAY’S FASTEST GROWING outdoor activities—hiking, kayaking, mountain biking, and rock climbing—require few, if any, licenses or fees. And unlike fishing and hunting gear, the equipment used for these activities does not generate revenue for public land management.

Although they are often considered “non-consumptive users,” these recreationists have come to expect well-maintained trails, well-managed forests and rivers, and search and rescue services—all of which require significant amounts of funding. Mountain biking requires trails, kayaking requires river access, and wildlife viewing requires wildlife habitat. Yet such users are often free riders who do not pay to play. Should these recreationists be required to pay a recreation fee or purchase a license, much like hunters and anglers do? Should there be an excise tax on outdoor equipment that helps fund outdoor recreation?

Should mountain bikers, kayakers, and other recreationists pay an excise tax to help fund outdoor recreation?

A range of alternatives have been explored to better fund natural resource conservation and public recreational use. At the state level, voluntary check-off programs, wildlife license plates, and conservation stamps have provided pulses of funding, but they have generally failed to deliver reliable and sustained support.

Mandatory mechanisms to generate funding have emerged in some states. A small portion of the general state sales tax in Missouri and Arkansas is dedicated to natural resource conservation. Real estate transfer taxes in Florida and South Carolina help fund the states’ natural resource agencies. And in Texas and Virginia, a share of the sales taxes collected on outdoor gear is directed to conservation projects in the states.

On the federal side, Congress has considered legislation to provide new appropriations for natural resource management but has stopped short of passing effective legislation—or has failed to provide funding for legislation they have passed. In 1980, for example, Congress passed the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, which authorized annual funding of $5 million for the development, revision, and implementation of state conservation plans and programs for non-game fish and wildlife. Although the program was reauthorized in 1986 and 1990, no funds have been requested by the administrations in power, and no funds have ever been appropriated by Congress.

In 1991, the Teaming With Wildlife initiative built a coalition of 3,000 organizations and businesses in favor of expanding an excise tax to a broad range of recreational equipment, including backpacks, sleeping bags, birdseed, binoculars, and field guides. Proponents estimated the new excise taxes would raise an additional $350 million annually for wildlife conservation. But opposition from the outdoor recreation industry and anti-tax members of Congress killed the proposal before it ever got off the ground. By 1998, the concept of an expanded excise tax for conservation was gone, and proponents were forced to try to carve out a piece from existing revenue sources—a reality we continue to face more than a decade later.

THE WILDLIFE RESTORATION and Sport Fish Restoration programs offer a proven, targeted, and accountable “user pays, public benefits” mechanism. Funded projects must result in an identifiable conservation outcome, qualify as “substantial in character and design,” and receive 25 percent matching funds from states and other partners. States receiving grant funds are audited every five years, risk assessments are conducted to ensure that grant requirements will be fulfilled, and any diversion of existing agency funds triggers a loss of funding. The programs are also administratively lean, with 98 percent of the funding going to on-the-ground projects in 2013.

At a time when demands on public lands are changing, budgets for state and federal land management are unable to keep up. Federal agencies face shrinking budgets with little prospect for growth, and although several states have approved mechanisms to expand funding beyond sportsmen’s licenses and excise taxes, these efforts are piecemeal and fragmentary. It’s clear that increased and reliable funding is needed by all states, not just a select few, and that the funding is needed to address strategic long-term efforts, not just the species or issues of the day.

In order to expand the “user pays, public benefits” model, the first step should be to unite a broad group of public land users under a single tent with a recognition that public lands require sustained management and funding—and that those management costs should be more fairly borne across a wider range of users. It’s time for hikers, mountain bikers, and others who enjoy the outdoors to join hunters and anglers in maintaining their playground.