Originally appeared in the National Review on June 5, 2015.

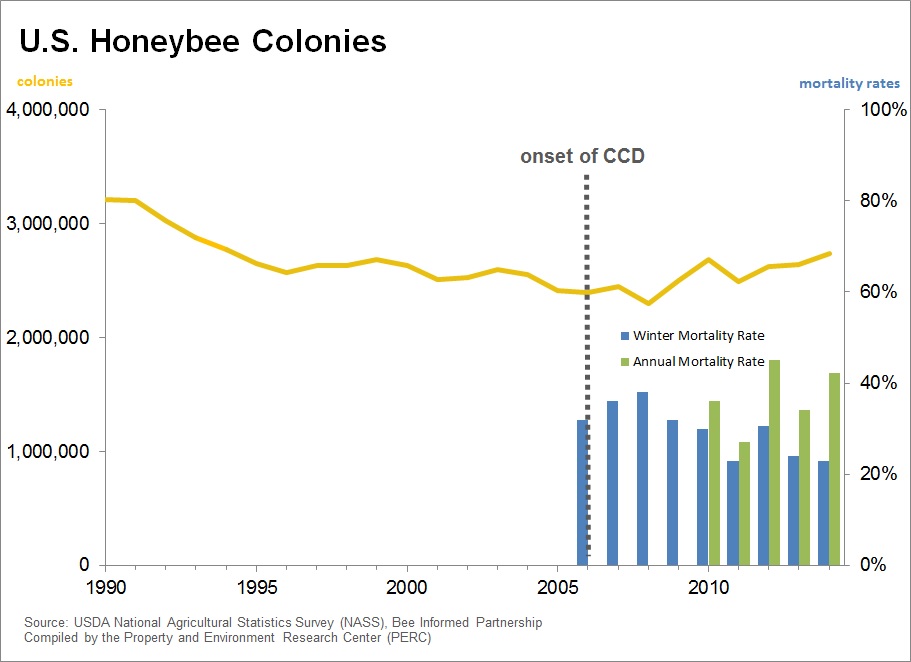

You’ve probably heard by now that bees are mysteriously dying. In 2006, commercial beekeepers began to witness unusually high rates of honeybee die-offs over the winter — increasing from an average of 15 percent to more than 30 percent. Everything from genetically modified crops to pesticides (even cell phones) has been blamed. The phenomenon was soon given a name: colony collapse disorder.

Ever since, the media has warned us of a “beemaggedon” or “beepocalypse” posing a “threat to our food supply.” By 2013, NPR declared that bee declines may cause “a crisis point for crops,” and the cover of Time magazine foretold of a “world without bees.” This spring, there was more bad news. Beekeepers reported losing 42.1 percent of their colonies over the last year, prompting more worrisome headlines.

Based on such reports, you might believe that honeybees are nearly gone by now. And because honeybees are such an important pollinator — they reportedly add $15 billion in value to crops and are responsible for pollinating a third of what we eat — the economic consequences must be significant.

Last year, riding the buzz over dying bees, the Obama administration announced the creation of a pollinator-health task force to develop a “federal strategy” to promote honeybees and other pollinators. Last month the task force unveiled its long-awaited plan, the National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators. The plan aims to reduce honeybee-colony losses to “sustainable” levels and create 7 million acres of pollinator-friendly habitat. It also calls for more than $82 million in federal funding to address pollinator health.

But here’s something you probably haven’t heard: There are more honeybee colonies in the United States today than there were when colony collapse disorder began in 2006. In fact, according to data released in March by the Department of Agriculture, U.S. honeybee-colony numbers are now at a 20-year high. And those colonies are producing plenty of honey. U.S. honey production is also at a 10-year high.

Almost no one has reported this, but it’s true. You can browse the USDA reports yourself. Since colony collapse disorder began in 2006, there has been virtually no detectable effect on the total number of honeybee colonies in the United States. Nor has there been any significant impact on food prices or production.

How can this be? In short, commercial beekeepers have adapted to higher winter honeybee losses by actively rebuilding their colonies. This is often done by splitting healthy colonies into multiple hives and purchasing new queen bees to rebuild the lost hives. Beekeepers purchase queen bees through the mail from commercial breeders for as little as $15 to $25 and can produce new broods rather quickly. Other approaches include buying packaged bees (about $55 for 12,000 worker bees and a fertilized queen) or replacing the queen to improve the health of the hive. By doing so, beekeepers are maintaining healthy and productive colonies — all part of a robust and extensive market for pollination services.

Economists Randal Rucker and Walter Thurman have carefully documented how these pollination markets work and how they respond to problems like bee disease. As it turns out, they work pretty well. A 2012 analysis by Rucker and Thurman found almost no economic impact from colony collapse disorder. (If anything, you might be paying 2.8 cents more for a can of Smokehouse Almonds.) They conclude that beekeepers are “savvy entrepreneurs” who have proven able to “adapt quickly to changing market conditions” with almost no impact on consumers.

What about beekeepers themselves? Rebuilding lost colonies takes extra work, but so far most beekeepers seem adept at doing so. Rucker and Thurman find that the prices for new queen bees have remained stable, even with increased demand due to higher winter losses. Pollination fees, the fees beekeepers charge farmers to provide pollination services, have increased for some crops such as almonds. But these higher pollination fees have helped beekeepers offset the additional costs of rebuilding their hives.

The White House downplays these extensive markets for pollination services. The task force makes no mention of the remarkable resilience of beekeepers. Instead, we’re told the government will address the crisis with an “all hands on deck” approach, by planting pollinator-friendly landscaping, expanding public education and outreach, and supporting more research on bee disease and potential environmental stressors. (To the disappointment of many environmental groups, the plan stops short of banning neonicotinoids, a type of pesticide some believe are contributing to bee deaths.)

This is not to deny that beekeeping faces challenges. Today, most experts believe there is no one single culprit for honeybee losses, but rather a multitude of factors. Modern agricultural practices can create stress for honeybees. Commercial beekeepers transport their colonies across the country each year to pollinate a variety of fruits, vegetables, and nuts. This can weaken honeybees and increase their susceptibility to diseases and parasites.

But this is not the first time beekeepers have dealt with bee disease, and they do not stand idly by in the face of such challenges. The Varroa mite, a blood-sucking bee parasite introduced in 1987, has been especially troublesome. Yet beekeepers have proven resilient. Somehow, without a national strategy to help them, beekeepers have maintained their colonies and continued to provide the pollination services our modern agricultural system demands.

“What are we doing on bees?” the president reportedly asked his advisers in 2013. “Are we doing enough?” With U.S. honeybee colonies now at a 20-year high, you have to wonder: Is our national pollination strategy a solution in search of a crisis?