Q&A with beekeeper Todd Myers on National Honey Bee Day.

On August 22nd, beekeepers observe National Honey Bee Day to promote local beekeeping and encourage “support of beekeepers in their own communities.”

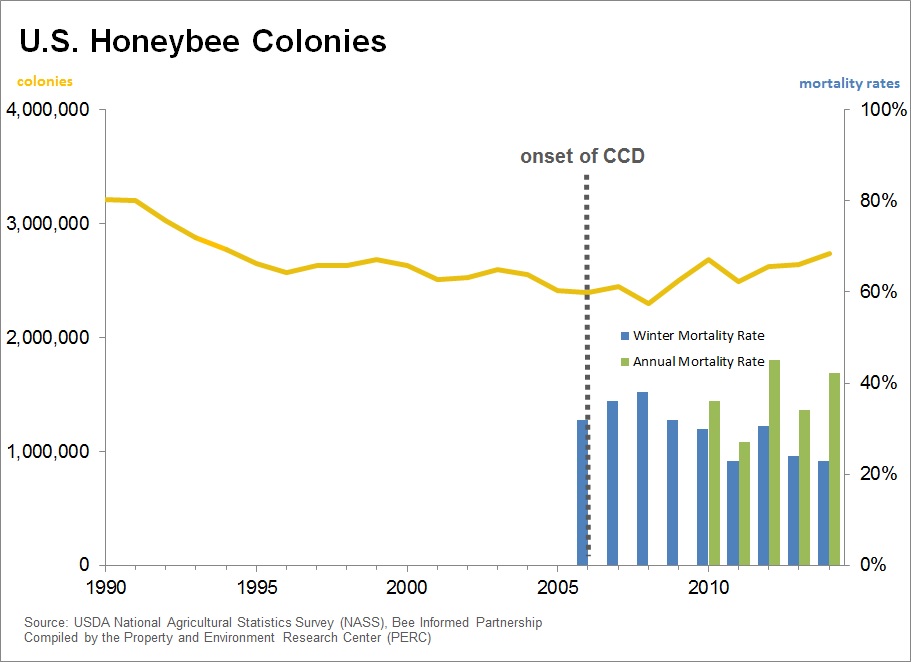

For centuries, even in the face of disease, parasites, and colony collapse, beekeepers have maintained healthy bee hives. And while most “beekeeping is local in nature,” this spring, the White House Pollinator Health Task Force unveiled a national strategy to reduce honeybee losses and restore pollinator health. Given the ability of beekeepers and their hives to rebound, and with U.S. honeybee colonies now at a 20-year high, do bees need a national pollination strategy?

To find out what practitioners think about a national honeybee policy, we talked to our friend Todd Myers, a beekeeper with hives in the foothills of the Cascade mountains. Todd, also an environmental policy analyst, has written about bees on the Washington Policy Center blog and for Business Pulse magazine.

Q: How did you get your start as a beekeeper?

A: My sister has been a beekeeper for about a decade and I got tired of hearing how interesting honeybees are, so I decided to give it a try. I am just a hobbyist beekeeper and I have four hives on a small farm near my house.

Additionally, having worked in environmental policy for more than 15 years, I see beekeeping as a great way to connect theoretical policy issues with the real-world challenges of natural resource management.

Q: What do you enjoy most about beekeeping?

A: Bees are just incredible. As much as you learn, there is always more to learn. There are always things you see that make you think and differing opinions that challenge your understanding. Everyone starts off asking me about honey, but when I tell them how bees can do calculus or how they create an immune system for the hive, people are amazed and interested in the complexity of honeybees. The more I learn, the more I work with them, the more fun it is.

Q: What is one component of the beekeeping business that most people are surprised to learn?

A: Most people don’t realize how significant the almond crop in California is to commercial beekeepers. A huge number of hives —accounting for more than 31 billion honeybees —travel to California early in the year. People would also be surprised to know how many beehives are near them, even in cities. Many people keep backyard beehives, even in areas people would think are simply too urban to support them.

Q: What role do bees play in the ecosystem?

A: Honeybees play an important role, but it is often exaggerated. First, honeybees are not native to North America. Second, many plants are wind pollinated. Third, there are many other pollinating insects. One often hears that without honeybees we would all die. That simply isn’t true. Furthermore, thanks to the resilience of beekeepers and their hives, there isn’t a risk that we are going to end up without honeybees.

None of this, however, means they aren’t important. Bees are critical for the almond industry and many other farmers who find that putting honeybees on their farm significantly increases crop yields. Bees are valuable pollinators. Their role need not be exaggerated to recognize how wonderful and important they are.

Q: What is Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) and why does it cause such concern?

A: Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), first identified in the U.S in 2006, is hard to pin down. It is most commonly associated with a situation where bees suddenly disappear from a hive, leaving it for no apparent reason. This, however, occurs in a tiny percentage of cases where a hive dies. According to Bee Informed, a national hive survey conducted annually by the USDA, CCD is responsible for less than ten percent of total hive loss. The vast majority of hive deaths are associated with other issues, such as starvation, harsh winters, and parasites like the varroa mite. For beekeepers, there are many other areas of greater concern. In the media and for politicians, however, it’s easier to focus blame on one thing, so CCD has been conflated with concerns about increased hive mortality.

Q: Rising concern for bees and CCD has led to the creation of a Pollinator Task Force to reduce honeybee losses nationwide. What do you expect to result from the White House plan?

A: Not much. Real solutions will come beekeeper by beekeeper based on the problems they face. The White House plan does some good things, like increasing forage for bees. But, it wasn’t a sudden drop in forage land that caused hive mortality to increase around 2006. So, this is a helpful step, but it doesn’t address the real cause, which the EPA, beekeepers, and others recognize as a confluence of factors, including the varroa mite and a range of other threats to healthy hives. The critical factor in reducing hive mortality will be the actions of beekeepers caring for their own hives.

That personal, local approach to hive mortality is important for a variety of reasons. For example, the USDA Bee Informed survey finds significant differences in the causes of hive mortality between commercial beekeepers and sideline/hobbyist beekeepers. This may be due to lack of skill among hobbyist beekeepers, who report a higher level of “don’t know” when asked why their hives died. It could also be that commercial hives face very different stresses – like being transported long distances and exposed to different crops – than the hives of hobbyists and sideline beekeepers. Ultimately, adaptation to these types of local circumstances will dictate the response and solution to the increase in hive mortality.

Q: What type of government policy could help beekeepers?

A: There is no silver bullet here because there is no single or uniform cause of honeybee loss.

First, there is some indication that corn ethanol subsidies have reduced forage for honeybees, increasing hive mortality in the Midwest. Randy Oliver, who runs the Scientific Beekeeping blog, noted that, “bee pasture in the Midwest is disappearing under the plow, largely due to our environmentally-irresponsible taxpayer-subsidized policies that encourage farmers to plant every square foot of land into corn.”

Second, the Administration correctly notes that we need more forage for bees, but what that means varies. In some cases it means adding cover crops for bees in fields that would sit fallow. In other cases, it means leaving existing plants for the bees. The Washington State Legislature, for example, passed legislation designed to increase bee forage in a way that doesn’t destroy the best forage plants – invasive species like Himalayan Blackberry and Japanese Knotweed.

Lack of beekeeping knowledge can also be a threat to honeybee populations. Traditionally, state beekeepers played an important role in improving the overall quality of beekeeping, teaching the many hobbyist and sideline beekeepers how to avoid and prevent the spread of disease. Given the financial situation, many states have cut or left empty the position of state beekeeper, and it is unlikely that these positions will be replaced or adequately funded. Beekeeping organizations and universities should work together to replace this service to improve the overall quality of beekeeping and share the latest science.

Ultimately, however, increasing the honeybee population is in the hands of those who know and care about them – individual beekeepers.

Q: Is there any sense of interdependence among beekeepers?

A: Beekeepers support each other by sharing information and promoting research on what is impacting bees. There is certainly competition for work in price and other aspects of beekeeping, but beekeepers have been very willing to participate in national surveys like Bee Informed and other efforts to understand the risks to honeybees.

Q: What are your expectations for the immediate and long term future of beekeeping?

A: While bee colonies have recovered since the 2006 CCD scare, there was an increase in hive mortality over the last year, so beekeepers still have work to do. But beekeepers have the best information and incentive to improve the health of honeybees. Lost hives can be expensive and beekeepers are the ones most likely to identify the causes and cures of hive death. The fact that the number of hives nationally is increasing is evidence that beekeepers can adjust even in very serious circumstances. It will take more time to put us on a consistent path to reducing hive mortality and understanding the risks to bees, but we are already seeing good steps forward and I am optimistic that we will continue to see improvement in the next decade.

Todd Myers is a hobbyist beekeeper, the Director of the Center for the Environment at Washington Policy Center, and the author of Eco-Fads: How the Rise of Trendy Environmentalism is Harming the Environment.

To learn more about honey bees, Colony Collapse Disorder, and its economic implications, read “Colony Collapse Disorder: The Market Response to Bee Disease,” the 2012 PERC Policy Series by Randy Rucker and Wally Thurman.