When winter’s snow and cold begin to weigh heavily on northern Michigan’s Isle Royale National Park, the island’s wolf population doesn’t lack for food, thanks to the burgeoning moose population. But that bounty might not be enough to protect the island’s few remaining wolves from being the last of their kind in the national park, as a shallow genetic pool threatens to doom them to extinction.

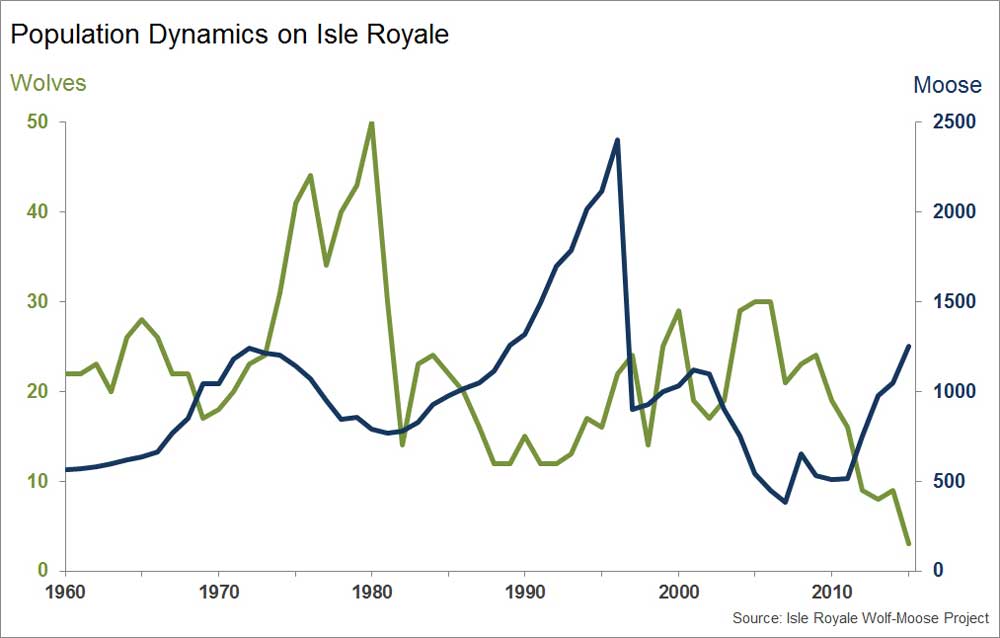

A dearth of new genes has left the wolves with severe inbreeding problems, and reproduction in recent years has fallen off. At the same time, the park’s moose population has more than doubled, to more than 1,000, over the past three years. If current trends continue, the remaining wolves could die off, and the growing moose population could remake the island’s forests by preventing regrowth of balsam fir, a signature tree of the boreal forest.

Park managers are embarking on an environmental assessment to examine options ranging from doing nothing to bringing in wolves that might infuse those on the island with a healthy dose of new genes. But that study, expected to get under way this year, could take three years or more, leading to calls that the National Park Service move forward with a genetic rescue.

“Does maintaining wolves on Isle Royale mean intervening more than once, to keep it on track? Yes, if the frequency of ice bridges continues on its historical trajectory, managed immigration might be required every few decades,” wrote Dr. Rolf Peterson, a biologist who long has studied the wolf-moose dynamics on Isle Royale, in an article for Yellowstone Science.

At Isle Royale, the Park Service seemingly faces a managerial conundrum: On one hand, the National Park Service Organic Act directs the agency to “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein” for the enjoyment of future generations. At the same time, the agency also has taken the position that it should “not intervene in natural biological or physical processes.”

For Isle Royale’s waning wolves, those two conflicting directives are meeting head-on. If they blink out, not only would it bring to an end “the longest continuous study of any predator-prey system in the world,” one that has spanned more than 50 years, but it also would lead to an out-of-control moose population.

THERE WERE NO WOLVES ON ISLE ROYALE when the park was established in 1940. The first wolves likely arrived 65 years ago by walking over 18 miles of Lake Superior ice that connected the island to an area near the Minnesota-Ontario border. From 1959 to 2011 the wolf population averaged 25 individuals, according to Dr. Peterson, but of late inbreeding has sent the wolves into a veritable death spiral. Contributing prominently to the problem has been the lack of “ice bridges” that tie the island to the Canadian mainland when winter weather turns bitterly cold and freezes the lake surface.

There has not been an invigorating infusion of off-island wolf genes since a Canadian male made that 15-mile ice bridge crossing in 1997. His arrival did provide a welcome burst of genes. He sired 34 offspring, which in turn produced at least 22 of their own.

“It was a total transformation of the population, and of wolf predation as well,” Dr. Peterson said during a phone interview. “In the next ten, 15 years, wolf predation went to the highest rate ever seen, and that had some remarkable effects on moose density. It pushed it down lower than we’ve ever seen, and (for) longer than we’ve ever seen. As a result, the trees responded incredibly. And it’s that response that will be truncated if predation continues to be largely absent.”

In short, if the moose population growth continues unabated, the animals will prevent a new generation of balsam fir from being established, he said.

By 2014, there were nine wolves remaining in the national park. Today, there are thought to be only three. There was hope that an ice bridge that formed in 2014 would enable wolves to arrive from Canada, but instead one female left and was killed by a gunshot wound near Grand Portage National Monument in Minnesota.

For the past two years, park managers have discussed island and wolf management with wildlife managers and geneticists from across the United States and Canada and have received input during public meetings and from Native American tribes of the area.

Last year, Isle Royale Superintendent Phyllis Green acknowledged there is a desire among the public for the Park Service to “bring new wolves to Isle Royale or to announce that we’re leaving their future gene pool up to wolves that may migrate from the north shore of Lake Superior when winters are cold enough for an ice bridge to the island.”

But, she said at the time, “This issue is bigger than only wolf genetics.”

“The plight of these nine wolves is a compelling story,” she continued, “but we are charged with a larger stewardship picture that considers all factors, including prey species, habitat, and climate change, which could, in a few generations, alter the food base that supports wildlife as we know it on Isle Royale.”

The Isle Royale wolf dilemma is a dramatic demonstration of the questions that the National Park System faces: What should be the future of America’s national parks?

Such a scenario, though, has prompted a suggestion that the Park Service alter how it manages wilderness and its resources not only at Isle Royale, which is 99 percent officially designated wilderness, but across the National Park System. In a paper presented last fall during a national park workshop in Bozeman, Montana, hosted by PERC, Dr. Daniel Botkin suggested that the agency should take a proactive role in managing some wilderness areas in the park system.

“The two laws that govern the national parks—the Organic Act of 1916 and, in some places including Isle Royale, the Wilderness Act of 1964—allow a set of human activities that lead to management that will be much more satisfactory to the public and to environmentalists and require less effort and cost than the existing alternatives,” wrote Dr. Botkin.

“At the heart of the matter is the prevailing view of American society about nature and people, especially about wilderness and people. The national park’s decision about the wolves of Isle Royale is consistent with, and reinforces, the still dominant belief in the balance of nature, the idea that nature is at its best left alone by human beings, and that left so, it achieves a balance that is constant, beautiful, most biologically diverse, and the only kind of nature within which a human being, allowed to be a visitor only, can find that spiritual connection to nature that our society associates with John Muir and Henry David Thoreau,” he added later in his paper. “If nature is only true if left alone, then we cannot interfere. But if nature is supposed to achieve a great balance, including a great chain of being—a place for every creature and every creature in its place—how can Isle Royale be changing? Many will believe there must be something people have done to destroy nature’s harmony.

“The Isle Royale wolf dilemma is a dramatic demonstration of the questions that National Park System faces throughout as its centennial in 2016 approaches. What should be the future of America’s national parks?”

FROM DR. BOTKIN’S PERSPECTIVE, the Park Service could utilize a range of three approaches to how it manages its wild lands:

1. No intervention. Let the area age on its own, let it essentially be an untouched by human managers. As such, the area would exist as kind of a baseline against which other areas that are managed to various extents could be compared.

2. In this second scenario, areas would be managed to appear as they were at a specific point in human history. “In the 20th century, this demand for reconstructing the past reached extremes with the work of zoologist Paul S. Martin, who called for resurrecting the biological diversity of sometime before 10,000 years ago, before American Indians arrived in the New World,” wrote Dr. Botkin. “He was asked in an interview published in American Scientist, ‘If you were suddenly put in charge of an effort to repopulate North America with species lost during the late Quaternary, where would you begin? What animals would you most like to see roaming the continent again?’ Martin replied, ‘I would like to see free-ranging elephants in secondary tropical forests of the Americas. Until the end of the Pleistocene, forest and savanna in the New World tropics supported three families of elephants.’”

3. Under the third scenario, which Dr. Botkin terms Dynamic Ecology Conservation Areas, landscapes would be “set aside to meet a variety of the reasons people value nature, and to sustain biological diversity, either for a specific species… (or) to perpetuate a specific kind of ecological community or ecosystem.”

FROM DR. PETERSON’S POINT OF VIEW, at Isle Royale some form of human manipulation, as envisioned for Dynamic Ecology Conservation Areas, makes sense in terms of the park’s wolf dilemma.

“I think preserving the wolf population there would preserve the ecological integrity of the park. I think it would be quite consistent with what Botkin was arguing,” said Dr. Peterson.

Too, he said, it likely would be consistent with recent views regarding managing a park’s natural resources in general and wilderness areas specifically.

“What the objectives of the Park Service are, in terms of natural resource management, according to the Revisiting Leopold Committee, which I think the director is pretty serious about, is maintaining ecological integrity in the face of what will be tremendous change” brought about by climate change, said Dr. Peterson.

Climate change, biodiversity, and the current state and understanding of ecosystem management all were unknown to A. Starker Leopold 50 years ago when he oversaw a report that became the National Park Service’s guide to managing wildlife in the parks. That so-called Leopold Report, though valuable for its time, was so obsolete that in 2011 Director Jarvis appointed a committee to rewrite the Leopold Report to make it applicable to the 21st century and its challenges.

In its pages the Revisiting Leopold report casts the National Park Service as the agency that can best rescue, protect, and preserve America’s natural resources. It envisions a National Park System that, while working with other federal, state, tribal agencies, and private groups, serves “as the core of a national conservation network of connected lands and waters.”

Against this scientific and policy backdrop, Superintendent Green is collecting all the various viewpoints and suggestions.

“At this point I am collecting them, reading them and will be passing them onto our planning team for review as we move forward with our planning process,” she said in an email. “It is inappropriate for me as a deciding officer to only discuss one study early vs. all relevant materials at the point of developing a preferred alternative or a final decision. I know you would prefer to discuss individual studies but I don’t feel that will do justice to all the material we will evaluate. Having said that, no options are off the table. All concepts will be evaluated.”

Whether the wolves will survive that analysis remains to be seen. Dr. Peterson, having watched the park mull the matter, is beginning to think park officials want the dilemma to sort itself out.

“They have been well aware of the problems since 2011. And they spent three years thinking about it, and now they’re going to spend another three years thinking about it,” he said. “It’s obvious that that sort of approach suggests that they don’t want to deal with it.

“Without new genes, (the wolves) will go extinct. I haven’t run into any geneticist that would argue otherwise.”

This article originally appeared in the National Parks Traveler.