PERC Reports Archive: VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1

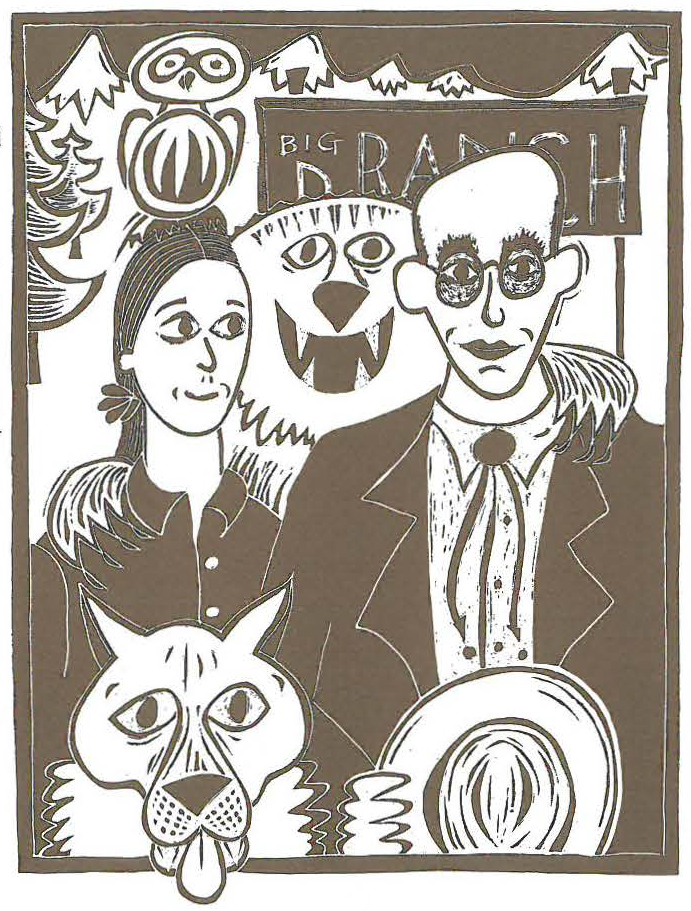

Dave Foreman, perhaps best known for co-founding Earth First!, now heads the Wildlands Project and is writing a book about the conservation movement that will expand on the following ideas.

There’s been some controversy at PERC over my libertarian orthodoxy. So I’ve been asked to address the question, “Is Dave Foreman a free market environmentalist?”

No. First of all, I’m not an environmentalist. I’m a conservationist. Environmentalism is concerned with human health; conservation is about wild lands and wildlife. Of course, I’m concerned with human health (particularly my own, even if I do eat bloody steaks, smoke cigars, and drink too much), but Nature is what I love. Moreover, the word “environment” makes my stomach curl up and shiver as it does when someone sneaks tofu onto my plate. “Environment” is as far from “Nature” as “Relationship” is from “Love.” It’s a word that only computers (not even computer geeks) should be allowed to use.

Second, although I think the free market is a great idea (it sure beats the hell out of corporate socialism), I do not believe in it like ayatollahs believe in Allah. Nor is private property a holy relic like a toenail of the Buddha under glass in a Sri Lankan temple. My ethical bottom line is not the free market, but Aldo Leopold’s land ethic: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” I am all for giving the market a first shot at achieving that ethic.

What I guess I really am is an old moss-backed conservative. I cast a suspicious eye on government (believe me, I have more reason to fear it than most of you do), but I don’t reject it out of hand. As a conservative, I don’t think people are perfectible. In fact, I think some of us are just plain bad. Both anarchism and libertarianism seem to base their rosy view on the perfectibility or basic goodness of everyone. But if we ever had either, it wouldn’t be long before the man on horseback took over. Thus, I believe in limited government. As a more traditional conservative, I also fear materialism. The dollar is a hell of a thing to pray to (Ayn Rand wasn’t the happiest person around).

I believe in public lands and in federal conservation laws. One of the great things about the United States is our heritage of public land. Federal conservation laws are necessary to manage public land, they are necessary for wildlife (who do not recognize political boundaries), and they are necessary for those problems which spread beyond states.

I believe the federal government has usurped far too many powers from the states. But I fear too much devolution to the states and counties. I’m from New Mexico, so this may have colored my views, but state government I find even more inept, corrupt, controlled by industry, and bureaucratic than federal. And counties? Well, the worst repression in the United States of America is a rural county if you express your reservations about local custom and culture. (A recent poll showed majority support for wolf reintroduction in rural southwestern New Mexico where there was believed to be no support for wolves. I wasn’t surprised since I lived in Catron County for 8 years if you are willing to share the land with lobos in Catron County, you don’t tell the local gentry your opinion.)

I think that conservationists have relied too much on federal government law and regulation. Part of the reason is that many conservationists (and even more environmentalists) have come from an activist liberal background. There’s a problem? Pass a law! Another reason is that big business has been so thoroughly irresponsible. By their lack of land stewardship and good citizenship, extractive industries (logging, mining, grazing, and energy) have created a demand for federal government action.

It has also been easier to pass federal laws than to work out good conservation through the free market or through voluntary agreements. I’m happy to see this is changing and I’m happy to be part of that change.

I believe that in following Leopold’s Land Ethic we should try free market and voluntary solutions first, and federal government solutions only later. Now in saying this, I am not recanting my past, nor am I newly converted to the market. I was baptized into politics by Barry Goldwater in 1964 and went on to be New Mexico State Chairman of Young Americans for Freedom in college. Earth First!, that bugbear of a radical, left-wing environmental group, was originally a right-wing wilderness group. We really were Rednecks for Wilderness back in the early 1980s.

The Wildlands Project, with which I now work, has a goal of protecting and restoring the ecological richness of North America. Private property and voluntary agreements play a big role in that. There are regions, though, like the Northern Forest of Maine and New Hampshire, where we support government acquisition of land- because of gross corporate irresponsibility. (By the way, shouldn’t free-marketers differentiate between private property—owned by individuals and families—and corporate property?)

Enough of my grumpy middle-aged rant. (When I go off on one of these tirades, my wife rolls her eyes and wonders if she’s married to her grandfather.) Where do I see market approaches as answers to conservation problems?

Certainly the Endangered Species Act should be more land owner-friendly. It is self-defeating and unfair to penalize private landowners for hosting threatened and endangered species. Let’s admit, though, that most of the horror stories about ESA agents running roughshod over property owners are as true as the story about the lady who put her poodle in the microwave to dry it off. It’s hard to work out a problem when one side’s stock in trade is a pack of lies.

I support Defenders of Wildlife’s compensation fund for livestock growers who lose stock to reintroduced wolves. Even better are DOW’s payments to ranchers who allow wolves to den on their ranches. Landowners who host endangered species should be honored as good members of the community and as good stewards of their land. It’s not just greenback compensation they deserve, but recognition as outstanding citizens.

I support open bidding on public land timber sales and grazing permits. Successful bidders should be allowed to choose not to cut the trees or to graze stock. I’m tired of head-butting with ranchers over grazing in wilderness areas and riparian zones. Conservationists should buy them out. The Diamond Bar Allotment in New Mexico’s Gila Wilderness is a good example. The battle has been a disaster for everyone involved—the rancher, the Forest Service, conservationists, and politicians. To study the problem, the Forest Service has already spent three times what the allotment is worth!

In this real world of declining federal budgets, new sources of funding are needed for public lands and conservation programs. User-pays seems like a workable and ethical approach. Entrance fees to national parks should be raised, private concessionaires should pay a fair fee, and the money should stay with the park for management. There should be a national fee for wilderness area recreation, and it should be used for wilderness management and to acquire private inholdings and grazing permits. A national sales tax on backpacking, climbing, and river running equipment should also go into this fund. A tax on birdseed, binoculars, and field guides should help fund the Endangered Species Act.

So am I a free-market conservationist?

Naw, I’m an agnostic. But I’m a friendly agnostic.

Editor’s Note: This essay generated several letters to the editor, which you can read here.