Not far from the city of Benicia in Solano County, California, sits an old hazardous waste dump. The site was once owned by the IT Corporation, whose primary business was the disposal of industrial waste. But today, part of the site is known as Ridge Top Ranch, and it’s home to an innovative conservation project to preserve endangered species.

The landfill was capped in 2002, and the state banned development around the facility to protect public health. When the IT Corporation entered into bankruptcy, the LandBank Group, a company that acquires and rehabilitates contaminated properties, obtained ownership of a majority of the ranch.

Despite its proximity to the San Francisco Bay Area, the property was devoid of development potential because the ranch is part of a buffer zone established around the hazardous waste site. Most landowners would have considered the property stranded and perhaps donated it to a land trust. But LandBank decided to turn a liability into an asset by creating a conservation bank.

How Conservation Banks Work

Under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, when a development project impacts a listed species, developers are often required to offset those impacts. Historically, this was done by enhancing and conserving nearby habitat for the endangered species. But this process is time consuming and expensive with no guarantee for success.

More recently, a new type of entrepreneur came up with another approach: Create a for-profit conservation bank. The idea is to take over the liability of species and habitat mitigation from developers. Conservation bankers purchase land that can be preserved and managed for the benefit of protected species. Long-term management is ensured through a conservation easement and an endowment fund to pay for habitat maintenance and monitoring.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issues credits to the conservation banker for the specific habitat that is preserved or restored. The conservation banker can then sell the credits to developers at a profit. Now, instead of having to find and secure endangered species habitat themselves, developers can buy existing credits from conservation bankers.

For several years, this model has helped mitigate impacts to wetlands and creeks. Credits are issued through mitigation banks, which are specific to wetlands and other sensitive aquatic resources. Conservation banks, on the other hand, are species-specific and relatively new to the marketplace, especially outside of California.

Identifying Habitat Potential

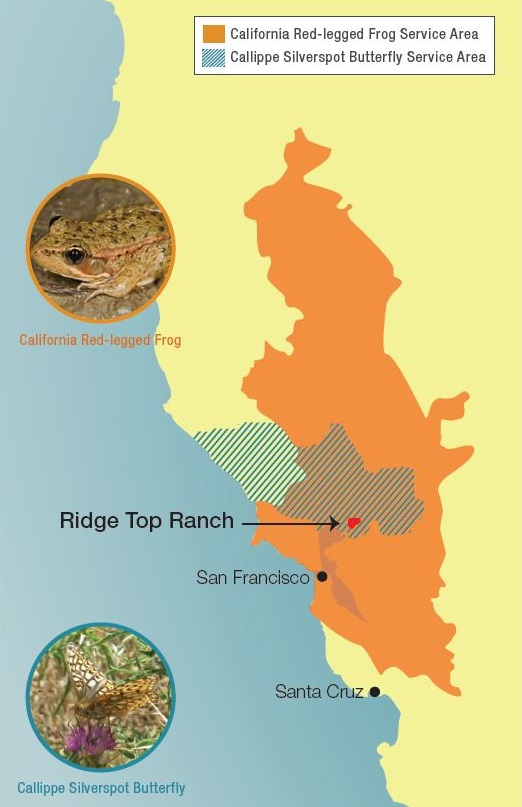

In the case of Ridge Top Ranch, WRA, a leading developer of conservation banks, first identified 745 acres of the ranch as potential habitat for the Callippe silverspot butterfly and the California red-legged frog based on its proximity to other occupied properties. Both species are listed under the Endangered Species Act, and much of their original habitat has been lost to development in central California.

Given the fast pace of residential development in the area, WRA determined there would likely be a profitable market for conservation credits for these two species. After conducting surveys, biologists identified several butterflies on the property and suitable habitat for both species. The California red-legged frog, however, was absent from the ranch. None were found in the cattle stock ponds on the ranch, even though they were known to live on nearby ranches. With the help of WRA, LandBank initiated a project to reintroduce the frog to the property.

Translocating Frogs

In collaboration with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, WRA worked to enhance habitat in two cattle stock ponds on the property for the threatened frog. This included planting wetland vegetation on which the frogs could attach their eggs and willow trees for overhead shade and cover.

Two egg masses were taken from a pond of a neighboring property and transferred to the restored ponds. Within a few weeks, tadpoles emerged, and later that year, juvenile frogs were observed. Once the frogs reached a certain size, they were implanted with tiny microchips so their location, weight, and size could be tracked. The following year, adult frogs were found in both ponds.

In February 2015, three new egg masses were observed. As of this publication, the egg masses have hatched and the tadpoles have metamorphosed into juvenile frogs, suggesting that the frogs are establishing themselves in their new habitat, despite multiple years of drought in California.

Protecting Butterfly Habitat

Habitat for the Callippe silverspot butterfly is also being restored on Ridge Top Ranch. The caterpillars rely on one species of native plant for their food: the golden violet, a low-growing wildflower that thrives in California’s perennial grasslands. Over the past century, however, European annual grasses and other exotic weeds have choked out many native plant species. This, in addition to habitat loss through development, has led to the decline of several species dependent on the native plants, including the Callippe silverspot butterfly.

WRA created a habitat management plan to improve habitat for the butterfly, primarily through managed grazing. By allowing livestock to graze the European grasses early in the growing season, there is less competition between them and the native golden violet.

Artichoke thistle, an invasive plant, has also invaded the property. A widespread eradication program is currently targeting the largest and densest patches of thistle. After that, weed management will focus on annual spot treatments of new or remaining patches. To date, the eradication program has reduced the amount of thistle on the property, and as a result, butterfly habitat is improving.

Financial and Ecological Success

Ridge Top Ranch demonstrates how conservation bankers are able to transform a property from a liability into an asset. If the LandBank Group had turned the property over to a land trust they would have received a tax write off but no additional revenue. Instead, for enhancing habitat, the mitigation banker received 739 frog and butterfly credits worth more than $20,000 each, based on current market values. As the San Francisco Bay Area grows and development expands further into the region, these mitigation values are likely to increase.

This project is a true win-win. Endangered species and their habitats are protected and enhanced without encumbering a profitable venture for the landowner. By harnessing markets for conservation banking, more properties will be protected and restored, creating important habitat for threatened species and generating broader environmental benefits for all.