DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

In January 2016, an armed militia group seized control of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in eastern Oregon. Their goal: to protest federal control over western rangelands. It’s the latest episode in a long history of conflicts over the use of federal lands in the West.

In this PERC Policy Series, Shawn Regan explores the underlying issues fueling conflicts such as the standoff in Oregon, as well as what might be done to resolve them. He argues that battles such as this are the result of federal land policies that encourage conflict instead of negotiation.

The central issue is the security and transferability of property rights to rangeland resources. Conflicts over grazing on federal lands are the product of poorly defined grazing rights and restrictions on the transferability of grazing permits. Environmental groups and other competing user groups often have little or no way to bargain with livestock owners to acquire grazing permits. As a result, federal rangelands are too often the subject of conflict and litigation instead of negotiation and cooperation.

This essay explores the challenges of resolving conflicts over the western range. It examines several case studies of innovative conservation groups who are attempting to overcome the barriers to trading rights to the federal rangeland. It also identifies opportunities for reforms that would promote more sensible—and more peaceful—solutions to conflicts over western rangelands.

This paper is part of the PERC Policy Series of essays on timely environmental topics. It is adapted from its original publication in Ranching Realities in the 21st Century (Fraser Institute, 2015) and supported by the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

Reviews

The national conversation about managing grazing on public lands is becoming more thoughtful and productive thanks to work such as this. Shawn Regan takes seriously the question of property rights in this comprehensive and understandable explanation of how convoluted and prone to conflict the legal and administrative structures that govern public lands have become.

— Leisl Carr Childers

Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Northern Iowa

Author of “The Size of the Risk: Histories of Multiple Use in the Great Basin”

The recent occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge headquarters, like the Cliven Bundy standoff of two years ago, is testimony to federal grazing policies that encourage political and legal conflict instead of mutually beneficial exchange. This timely report makes a persuasive case for facilitating exchange through secure and transferable private rights in the use of public rangelands.

— James Huffman

Dean Emeritus, Lewis & Clark Law School

Grazing on the federally managed public lands has been a conundrum, often governed by rigid and inflexible positions, as well as laws that make innovation difficult. There are several policy options worth discussion and PERC has made a case for several: rethinking base property requirements, the use-it-or-lose-it policy, and the requirement that permittees be in the business of grazing livestock.

— John Freemuth

Professor of Public Policy, Boise State University

Senior Fellow for Environment & Public Lands, Cecil D. Andrus Center for Public Policy

Introduction

For a few short weeks during the spring of 2014, the intricacies of the U.S. federal grazing system garnered national attention. Major newspapers ran front-page stories. Television crews rushed to cover the issue live from the western range. Cable networks broadcast videos of cattle grazing on the evening news. If only for a moment, it seemed as though the entire nation was debating federal grazing policy as a tense standoff unfolded between the Bureau of Land Management and one Nevada rancher named Cliven Bundy.

Mr. Bundy, as the story went, was a scofflaw—a recalcitrant rancher who illegally grazed his cattle on federally owned lands for decades without paying the required federal grazing fees. An outspoken critic of the BLM, Bundy refused to acknowledge the federal agency’s authority over the land outside Bunkerville, Nevada. “As far as I’m concerned, the BLM don’t exist,” he said during a presentation a few months earlier. He had a vested right to graze cattle on the vast rangelands outside of Bunkerville, he said, just as his family had for generations.1

“When I decided that I was paying grazing fees for somebody to manage me out of business, I said, ‘Hell no,’” Bundy told the audience in a presentation in February 2014. “And what did I tell them? I no longer need your service as a manager over my ranch, and I’m not going to pay you for that no more.”

The BLM, however, disagreed, and in April 2014 the agency began rounding up hundreds of Bundy’s cattle from the federal rangeland. The agency claimed that Bundy owed nearly $1 million in unpaid grazing fees and fines. The cattle were not only trespassing; they were trampling sensitive habitat for the desert tortoise, a federally protected species. The BLM dispatched hundreds of federal agents along with contract cowboys and helicopters to descend upon the Nevada desert to capture, impound, and remove Bundy’s cattle from federal land.2 When Bundy refused to back down, the situation escalated quickly. Dozens of anti-government activists rallied in support of Bundy to stop the roundup and fight back against the BLM.

To many observers in the East, the roundup was seen as a clear example of federal overreach. Within a few days, a full-on range war was brewing in Bunkerville. Mobs of angry protesters and armed militiamen confronted BLM agents as they attempted to corral Bundy’s cattle. At one point, guns were drawn. One protestor, one of Bundy’s sons, was shot by federal agents with a stun gun.

The standoff captured the nation’s attention. Almost overnight, Bundy became an icon in conservative media outlets for standing up against an oppressive and powerful federal agency. In other media circles, Bundy was portrayed as a “welfare cowboy” who blatantly disregarded the law and grazed his cattle at the expense of U.S. taxpayers. And to others, he was simply a criminal with a rogue militia gang—a clear indication that the violence and lawlessness of the wild, wild West is still alive and well in the deserts of Nevada.

In the end, the BLM backed down, citing concerns over the safety of their employees and the public. The cattle were released back on to the federal rangeland, where they remain today. The range war in Bunkerville gradually defused, and Bundy emerged unscathed. But for Bundy, the limelight did not last for long. A few days later, he was recorded making offhand racist remarks to a journalist and was swiftly denounced by the media. Almost as quickly as it began, the grazing debate—along with Bundy himself—faded from the headlines.

The Rest of the Story

The conflict between Cliven Bundy and the BLM transformed federal grazing policy into a salient political issue in the minds of many Americans, if only for a brief time. Bundy’s story, however, is far more complicated than it was portrayed on national television. The narrative that emerged in the media implied that the conflict was straightforward: A rancher refused to pay his grazing fees and, as a result, was nearly evicted from the land.

But in fact, the standoff on the Bundy ranch was the product of a longstanding confrontation between ranchers and environmental groups over the nature and security of federal grazing rights in the United States. That debate is embedded within the unique and complex history of U.S. grazing policy. It’s a story that illustrates one of the central challenges facing grazing policy today: how to resolve conflicting demands on the federal rangeland in an era of new and competing environmental values.

Consider the more nuanced version of Bundy’s dispute: For generations, Bundy’s family grazed cattle on the vast rangelands of the western United States. Like many ranchers in the West, Bundy had a federal grazing permit, issued by the BLM, which authorized him to graze a certain number of cattle on the 160,000-acre Bunkerville Allotment in southeastern Nevada. The federal grazing system requires that grazing permittees must own certain private properties that are legally recognized by the federal government as qualifying for federal grazing privileges.3 In this case, Bundy’s right to graze cattle on federal land was dependent upon his ownership of a 160-acre parcel located in Bunkerville, Nevada.4 In effect, his grazing permit was attached to this particular “base property.” Along with the ranch, Bundy also secured groundwater rights, which together with the base property enabled him to secure and maintain grazing privileges to the Bunkerville Allotment. The value of Bundy’s property was enhanced by and dependent upon the public grazing privileges it provided to the nearby allotment.

For years, Bundy grazed his cattle on the federal grazing allotment and paid the required grazing fees—which typically amounted to approximately $1.35 per animal unit month (AUM).5 But in 1993 the federal government made an adjustment to Bundy’s grazing permit. Under pressure from environmental groups, the agency significantly reduced the number of cattle that Bundy was authorized to graze on the allotment in an effort to protect desert tortoises, a species that had recently been declared as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This modification had a significant effect on Bundy’s cattle operation as well as the value of his base property. Because Bundy’s ranch came with federal grazing privileges, reductions to his grazing permit could cause a corresponding reduction in his base property value. And with just 160 acres of deeded private land—nowhere near the amount necessary to sustain a cattle herd in the arid West—reductions such as this could threaten Bundy’s future livelihood as a cattle rancher.6

Bundy refused to accept the BLM’s modified grazing permit and continued grazing his cattle on the Bunkerville Allotment. He also refused to pay the grazing fees and trespass fines levied against him. In 1994, the BLM formally revoked his grazing privileges for “knowingly and willfully grazing livestock without an authorized permit,” setting in motion Bundy’s decades-long battle with the BLM.7 After several court orders to remove the cattle and ban Bundy from grazing on public lands—in addition to nearly $1 million in grazing fees and fines owed by Bundy—the conflict finally reached a boiling point in April 2014 when the federal government began to roundup the trespassing cattle.

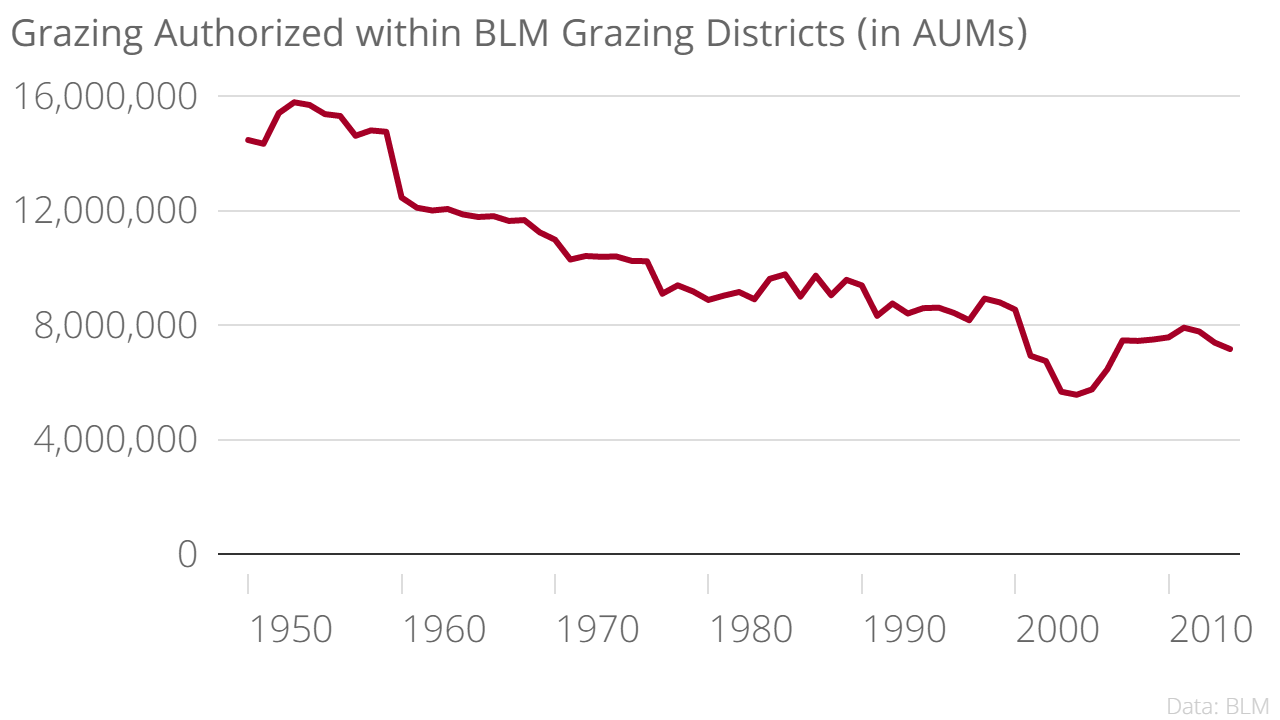

Bundy’s story is not unique. Ranchers across the West increasingly face similar challenges to their traditional grazing use of the federal rangeland. This has contributed in part to a general decline in grazing on federal rangelands and a perception among many ranchers that their future is threatened by the emergence of environmental regulations.8 Today, the amount of grazing authorized on BLM land is half of what it was in 1954.9 Bundy’s case is simply the most salient and well-documented dispute in recent years.

This more nuanced story illustrates the central challenge explored in this essay: In the United States, grazing conflicts such as Bundy’s are born out of a federal grazing system that encourages conflict, not negotiation. Competing user groups often have no way of coming together to resolve conflicting demands except through top-down political or judicial means. Environmentalists, for their part, frequently file legal challenges over land management, forcing federal land agencies to restrict grazing rights and declare more areas off limits to grazing and other historic land uses. Environmental statutes such as the Endangered Species Act and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) serve as regulatory weapons to reduce the impacts of grazing on federal lands, undermining the traditional grazing rights. The result is a federal land system strangled by what former U.S. Forest Service chief Jack Ward Thomas described as a “Gordian knot” of litigation and regulation.10

The problem of the “Gordian knot” is intensified by the vast reach of the federal government’s authority over western lands in general and over western livestock grazing in particular. Federal agencies control nearly half of the land in the western United States, including more than 60 percent of Idaho, 67 percent of Utah, and more than 80 percent of Nevada.11 As a result, livestock grazing in the West is a federal land issue in many cases. Due to the relatively small amounts of private land in the West, along with the region’s arid conditions, which require large amounts of land to sustain livestock operations, western ranchers have relied on access to federal land for forage resources for more than a century.

Today, the BLM administers nearly 18,000 grazing permits and manages more than 21,000 grazing allotments on 155 million acres of public lands managed for livestock grazing.12 The U.S. Forest Service also administers a federal grazing program in the agency’s national forests and grasslands, comprising more than 95 million acres of land with nearly 6,000 permittees.13 In 2013, together, these agencies provided 15 million AUMs worth of forage resources for livestock grazing, or enough forage to feed 15 million cow-calf pairs or 75 million sheep or goats for a month.

Federal control over grazing in the American West means that debates over who gets to do what on the land are ultimately determined through political or legal processes rather than a market process. As a result, disputes are ridden with acrimony, litigation, and in some cases even violence or intimidation. In 1997, when the BLM proposed to significantly reduce public land grazing in Owyhee County, Idaho, the local sheriff threatened to throw federal agents in jail if they enforced the reductions.14 Prior to the standoff on Bundy’s ranch, Nevada ranchers had repeatedly resorted to violence and intimidation to resist similar grazing restrictions. Environmentalists have even sabotaged grazing operations by cutting barbed-wire fences and otherwise disrupting public land grazing practices.15

This essay examines the U.S. federal grazing system and explores its ability—or its inability—to resolve competing demands through negotiation rather than conflict. Federal grazing policies in the United States have largely proven unable to reconcile conflicting demands on the western range. In many cases, existing policies may even exacerbate the problem. The central issue, this essay will argue, is the security and transferability of property rights to rangeland resources. In particular, conflicts over grazing on federal lands are the product of poorly defined grazing rights and restrictions on the transferability of grazing permits. Environmental groups and other competing user groups effectively have no way to bargain with livestock owners to acquire grazing rights. Their ability to trade is prohibited or severely limited under existing federal grazing policies. As a result, federal rangelands are too often the subject of conflict, litigation, or regulation, rather than exchange, negotiation, or cooperation.

In the sections that follow, this essay explores these challenges and identifies key issues and opportunities for reform. It offers a framework for thinking about how grazing conflicts are resolved, borrowing from a theory known as raid or trade, and explores several efforts by conservation groups and private landowners to overcome the barriers to trading rights to the federal rangeland. The essay concludes by exploring the lessons learned from these limited efforts in the United States and discusses how the federal grazing experience might inform rangeland policy in other jurisdictions. In the process, it suggests several opportunities for reforming the U.S. federal grazing policy to promote more sensible, peaceable solutions to conflicts over the western rangeland.

Raid or Trade?

How to resolve competing demands over the western range is the most challenging and important federal grazing policy question today.

This question, explored in the context of the federal grazing system, can be examined within the raid-or-trade framework introduced by Anderson and McChesney to explain violence on the American frontier.16 Anderson and McChesney modeled an important decision that white settlers and Indians faced when conflicts arose over land claims: Would the two groups fight or negotiate to resolve disputes? Or in other words, would they raid or trade?

According to Anderson and McChesney, the answer depended on the relative costs of raiding and trading. If the costs of fighting decreased, perhaps because one side developed superior weaponry or commanded significantly more manpower, then disputes were more likely to turn violent. But if the costs of negotiation fell, perhaps because a tribe’s land rights were clearly defined and recognized by other tribes, then groups were more likely to bargain to get what they wanted. Trade, after all, is mutually beneficial. Fighting is costly. Looking through the frontier accounts of Indian-white relations, Anderson and McChesney found that this straightforward economic logic explained much about the interactions between the two competing groups.

The raid-or-trade theory extends beyond the old western frontier, however, and is also helpful for understanding modern-day conflicts over western rangelands. On federal grazing lands today, it is simply too easy to raid and too costly to trade. Environmental groups, for instance, use policies such as the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act as regulatory weapons to force restrictions on federal grazing to protect land and species. Raids like the one on Cliven Bundy’s ranch are common across the West, as ranchers’ grazing permits have been reduced or suspended by the federal government at the behest of environmental groups or as a result of decisions coming through the legal system. Because federal grazing permits are attached to specific base properties, raids such as these can cause substantial losses for ranchers, creating considerable controversy and fueling bitter political battles.

The institutions that govern federal grazing lands have failed to evolve to accommodate new environmental demands in a manner that encourages trading instead of raiding. The blueprints of the federal grazing system were conceived at a time when environmental demands were far less prevalent. Today, however, that system has proven unable to reconcile competing environmental demands in an effective or cooperative way.

In particular, current federal grazing policies impose significant barriers to resolving conflicting demands through trading. Competing user groups have little or no means to exchange rights to federal rangeland resources. In contrast to other areas of western natural resource management, such as western water law, in which many states allow environmental groups to purchase water rights from agricultural rights holders and hold them for conservation purposes, no similar trading mechanism has emerged on a large scale within the U.S. federal grazing system.17 As a result, raiding is far more common than trading as a means of resolving rangeland disputes on federal land.

The raid-or-trade model provides a clear and useful lesson for rangeland management: If property rights are well defined and transferable, then disputes among even the most diverse groups are more likely to get resolved peacefully and in a mutually beneficial way. Therefore, if grazing rights are clear and tradable, then conflicts over the federal rangeland are more likely to get resolved through trading. Thus, finding ways to define and secure grazing rights will encourage more trading and less raiding on federal rangelands.

As Mr. Bundy discovered when his grazing rights were curtailed in the early 1990s, federal grazing permits are far from secure property rights. They can be reduced or revoked by the federal government at any time. Federal grazing rules refer only to “grazing privileges” rather than formal grazing rights, and the security of those privileges have been gradually weakened by environmental regulations.18 Despite repeated attempts to clarify and establish more formal rights to rangeland resources, the federal government has been unable or unwilling to grant secure grazing rights.

There have been several proposals to establish secure and transferable forage rights on the federal rangeland as a means of resolving grazing disputes through trading. In 1963, Delworth Gardner, a leading agricultural economist, called for the government to “create perpetual permits covering redesignated allotments… and issue them to ranchers who presently hold permits in exchange for those now in use.”19 These new permits “would be similar to any other piece of property that can be bought and sold in a free market.” Likewise, resource economist Robert Nelson has called for the creation of a formal “forage rights” on federal rangelands.20 These rights could be traded to environmental groups to use for non-grazing purposes such as conservation.

Economists such as Gardner and Nelson are not alone in their recommendations. Mark Sagoff, a leading environmental philosopher, views markets in tradable grazing permits as a practical institutional arrangement that would “enable traditional antagonists to gain the benefits of exchange.”21 In addition, several prominent environmental activists and conservation groups have also acknowledged the benefits of establishing clear and transferable grazing rights. Dave Foreman, a radical environmentalist and founder of the Earth First! Movement, has expressed support for transferable grazing rights that can be purchased by environmental groups, arguing that the most practical and fair way for environmentalists to resolve grazing conflict was simply “to buy ’em out.”22 Andy Kerr, another environmental activist, has likewise advocated for transferable grazing permits that could be bought out by environmental groups or the federal government itself. Kerr argued that under current federal grazing policies, environmentalists have “no option but to exercise traditional environmental protection strategies in the areas of administrative reform, judicial enforcement, and legislative change” which “can cause social and political stress and are not always successful.”23

The establishment of formal grazing rights would likely promote more responsible rangeland management and alleviate the bitter conflicts that are common over grazing. “The lack of any clear rights on federal rangelands has resulted in blurred lines of responsibility which have been as harmful to the environment as they have been to the conduct of the livestock business,” writes Nelson.24 He argues that the creation of secure and transferable grazing rights on federal lands “offers the best means available for resolving the severe gridlock and polarization that have beset federal rangelands for the past quarter century or more.” Environmental groups “would have a realistic way to accomplish their goals, other than by seeking to influence the exercise of government command-and-controls”—that is, they could trade instead of raid, allowing the debate over western land use to no longer be resolved solely by federal regulations, bureaucratic planners, or judges, but rather “by the competitive workings of the marketplace.”25

Despite these calls for reform, however, efforts to establish clear and secure grazing rights have had limited success. A few environmental groups have completed buyouts of grazing permits to protect grazing allotments, but these have occurred on a limited basis and are carried out at high costs. Other groups have purchased base properties but in some cases have been forced to graze cattle to comply with the use-it-or-lose requirements of the current federal grazing system. In other cases, environmental groups have been able to work within existing federal grazing policies to accomplish their conservation goals, but these efforts are limited. Despite these small victories, raiding is still rampant on federal grazing lands, and the reforms necessary to encourage more trading have not come.

Environmental values are increasingly recognized as important and legitimate demands on the western rangeland, but they currently have little or no way to express themselves other than through controversial regulatory or legal processes, which have the potential to rip apart the social fabric of many western communities.

History of U.S. Grazing Policy

To understand why raiding displaces trading on the federal rangeland, consider the history of the U.S. federal grazing system, which has evolved over more than a century. The evolution of federal grazing policy helps explain today’s complicated—and in many ways antiquated—federal grazing system. To many observers, the contours of today’s system defy explanation apart from this historical understanding, which helps explain many of the barriers to resolving modern-day conflicts on the western range.

The Open Range

“There is perhaps no darker chapter nor greater tragedy in the history of land occupancy and use in the United States than the story of the western range,” notes a 1936 Department of Agriculture report.26 In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, overgrazing was common on the public domain rangelands of the western United States. U.S. land policies gradually encouraged more settlers to venture westward, where they were met with vast open rangelands on which they grazed livestock, primarily cattle and sheep. Today, this unregulated system of open-range grazing is often seen as the root cause of severe range depletion, erosion, and other devastating environmental consequences.

However, as many historians have documented, the legacy of uncontrolled grazing on public rangelands was largely the result of federal policies that limited the establishment of property rights to the open range and, in effect, created an open-access rangeland regime.27 U.S. land policies such as the Homestead Act limited settlers to 160-acre claims, which were ill-suited for the realities of the western landscape. Because traditional agriculture practices were often impractical in the West’s dry and remote landscapes, grazing was the dominant land use of the era. Even with the expansion of homestead claims to 640 acres in 1916, this was still not enough land in many areas of the arid west to sustain livestock on a year-round basis.

The General Land Office, the former agency responsible for public domain lands in the United States, refused to issue larger homestead claims that were better suited for the West’s arid landscape. Due to the land’s low carrying capacity, and the inability of settlers to establish rights to properties to sustain ranching operations, livestock owners relied upon the public domain without formal rights to the rangeland. Predictably, open-access conditions often prevailed during this period, resulting in overgrazing, erosion, and poor livestock conditions.28

Taylor Grazing Act

Efforts to regulate public domain grazing began in the early twentieth century, but it was not until 1934 that Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act, which created the foundation for the federal grazing system in the United States today.29 Responding to the perception that the self-interested private actions of ranchers were the root cause of overgrazing and abuse on the public domain, the act established federal control over grazing on the remaining public domain lands. The act was intended “to stop injury to the public grazing lands by preventing overgrazing and soil deterioration” as well as “to provide for their orderly use, improvement, and development.”30 The act also led to creation of the U.S. Grazing Service, which later merged with the General Land Office to form the Bureau of Land Management in 1946.31

The Taylor Grazing Act gave the Secretary of the Department of the Interior the authority to create regulated grazing districts on unclaimed public lands, issue permits to graze livestock on these lands, and charge a grazing fee. Ranchers were eligible to receive grazing permits if they met two conditions: First, they must have ownership of a nearby “base property” and second, they must demonstrate a recent history of grazing on the open federal rangelands. The base property, which may also include water rights, is often a nearby ranch that qualifies as a base for the permittee’s livestock operation, as determined by the BLM. Grazing permits cannot be held by or transferred to individuals that do not hold qualifying base properties. When these base ranches are sold, the permits are transferred along to the new property owners.32 Permits are issued for a period of up to ten years, and permit holders have priority over others to renew the permit for additional ten-year periods without competition.

Under the act, preference was given to those within or near a grazing district and who are “engaged in the livestock business, bona fide occupants or settlers, or owners of water or water rights,” largely to ensure that ranchers who had been using public rangelands would still be able to graze cattle on the federal rangeland. The act also states that “grazing privileges recognized and acknowledged shall be adequately safeguarded,” but it states that the issuance of a grazing permit “shall not create any right, title, interest, or estate in or to the lands.”33 The Secretary may also “specify from time to time numbers of stock and seasons of use.”

Federal Land Policy and Management Act and Public Rangelands Improvement Act

Enacted in 1976, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) directs the BLM to manage its lands “under principles of multiple use and sustained yield” in a manner that protects “scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resource, and archeological values.”34 The act did not repeal the major provisions of the Taylor Grazing Act, but rather it expanded the other recognized uses of public grazing lands to include environmental and aesthetic values, as well as provided federal land planning procedures. FLPMA also marked the official end of homesteading by repealing the earlier homestead acts. The act established that the federal government was no longer in the business of disposing of public land, and instead would retain federal ownership of the remaining federal lands.

The Public Rangelands Improvement Act (PRIA), passed in 1978, further clarified the BLM’s grazing management goals. The act specifically called for improving range conditions on BLM lands. The policy led to a number of conservation-oriented range management projects and cutbacks in grazing permit allocation levels, all aimed at promoting the improvement of public rangeland conditions. Together with FLPMA, the act shifted the BLM’s priorities from livestock and grazing management to the protection of specific rangeland resources, including riparian areas, threatened and endangered species, and historic and cultural resources.

PRIA also provided a formula for determining annual federal grazing fees on both BLM and Forest Service lands.35 Grazing fees are paid based on the number of animals grazed per month, known as animal unit months (AUMs). PRIA was designed to establish an “equitable” grazing fee that ensures that the western livestock industry is protected from significant economic disruptions. The grazing fee formula is adjusted each year based on three factors: (1) the rental charge for grazing cattle on private rangelands, (2) the sale price of beef, and (3) the cost of livestock production. Annual fee adjustments cannot exceed 25 percent of the previous year’s fee. The minimum fee that can be charged is $1.35 per AUM. Since 1981, the federal grazing fee has ranged from $1.35 per AUM to $2.31 per AUM. The federal grazing fee in 2015 was $1.69.36

PRIA also defined the term “grazing preference” as “the total number of animal unit months of livestock grazing on public lands apportioned and attached to base property owned or controlled by the permittee.”37 This definition remained until 1995, when the BLM issued new regulations that many believed weakened the security of ranchers’ grazing rights to federal land. The 1995 regulations introduced the term “permitted use” to refer to the authorized number of AUMs allocated during the applicable land use plan. In other words, grazing privileges could be curtailed as part of the broader federal land-use planning process. Many ranchers argued that these new rules effectively reduced the security of their grazing privileges by eliminating their prior right to graze predictable numbers of livestock from year to year. Moreover, they argued that the new regulations violated the Taylor Grazing Act’s provisions that required grazing privileges to be “adequately safeguarded.”38

Grazing Rights vs. Privileges

The enactment of FLPMA and PRIA, along with the new BLM regulations promulgated in 1995, highlights a longstanding debate over the nature and security of grazing rights to federal rangelands. Do ranchers have secure grazing rights to public lands, or do they merely have grazing privileges that can be reduced or revoked by federal agencies? This question has been at the center of many rangeland conflicts over federal range policy.

The question still remains unclear today. Public land agencies insist that grazing permittees do not have actual property rights to rangeland resources. Indeed, the Taylor Grazing Act speaks only of grazing “privileges,” not formal rights. The act states that the secretary of the Interior can specify “from time to time numbers of stock and seasons of use.” However, the act also states that grazing privileges “shall be adequately safeguarded.” Moreover, in many ways, grazing permits have historically been perceived as implying formal grazing rights.39 Federal capital gains and estate tax calculations reflect the value of the grazing permit. Ranchers’ base property values are affected by the grazing permits attached to them. The values of grazing permits are effectively capitalized into the value of these base properties. Banks collateralize loans to ranchers on the basis of grazing permit values. In effect, grazing on federal lands has historically been treated as a right in practice, even if only considered a “privilege” on paper.

The U.S. Supreme Court took up several related issues in Public Lands Council v. Babbitt (2000). The Court affirmed the BLM’s authority to reduce grazing levels to comply with new environmental laws and upheld the 1995 regulations that redefined grazing preferences. The Court also took up the issue of whether environmental groups could acquire grazing permits for “conservation use,” a practice that was prohibited under the existing rules. Specifically, the Court focused on whether grazing permittees were required to be engaged in the livestock business. In the end, the Court upheld an appeals court ruling that a BLM regulation that allows conservation use but excludes livestock grazing for the full term of a grazing permit was invalid.40

Apart from the legal debate over grazing rights and privileges, the inability of the federal government to clearly define property rights to rangeland resources has contributed to the rangeland health issues on federal lands. Economists such as Gary Libecap have argued that insecure tenure encourages overstocking and discourages investments in rangeland improvements.41 Libecap identifies “fundamental flaws” in the current institutional arrangements that rely on bureaucratically assigned grazing rights.42 Since bureaucrats do not hold property rights to the rangeland resources, they do not bear the costs or receive the benefits of their management policies. As a result, Libecap argues that grazing rights are inherently tenuous because agencies continually reallocate rangeland resources and adjust grazing privileges to meet changing political conditions. Moreover, without the right to acquire grazing permits for conservation uses, environmental groups are forced to rely on these changing and uncertain political processes rather than individual market transactions.

Even today, despite federal policies intended to protect and preserve rangeland conditions, rangeland health suffers. In 1994, the BLM reported that rangeland ecosystems are still “not functioning properly in many areas of the West. Riparian areas are widely depleted and some upland areas produce far below their potential. Soils are becoming less fertile.”43 In particular, the agency concluded, riparian areas “have continued to decline and are considered to be in their worst condition in history.” According to the BLM, nearly a quarter of current BLM grazing allotments are not meeting or making significant progress toward meeting the agency’s own standards for land health.44 A recent assessment of BLM grazing practices by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, a watchdog group, found that 29 percent of the agency’s allotted lands (16 percent of allotments) have failed to meet the BLM’s standards for rangeland health due to livestock impacts.45

Barriers to Trade

The lack of well-defined and transferable federal grazing rights presents serious obstacles to resolving rangeland disputes in a cooperative and mutually beneficial manner. These obstacles have important effects on the decisions to raid or trade among groups seeking to influence federal rangeland policy. As a practical matter, conservation groups have been prohibited from acquiring grazing permits to use for conservation purposes, effectively taking the trading option out of the equation.

A detailed understanding of the history of U.S. federal rangelands helps identify several specific obstacles to trading within the federal grazing system.

First, the use-it-or-lose-it provision requires ranchers to graze livestock on their permitted allotments or risk losing their grazing privileges.46 If permittees abandon grazing activities on a significant portion of an allotment, the BLM would have an obligation to transfer the permit to another rancher willing to use the allotment for grazing purposes. While under some conditions grazing allotments can be “rested” for short periods, permittees cannot end grazing altogether on permitted allotments. This clearly creates obstacles for environmental groups attempting to acquire grazing permits for non-grazing purposes.

Second, the base property requirements under the Taylor Grazing Act create similar barriers to trade. That is, groups seeking to acquire grazing rights must purchase or already own qualifying private base properties to which grazing privileges can be assigned.47 Moreover, unlike the grazing system on state trust lands in the United States, grazing rights are not determined by competitive bidding.48 This requirement raises the cost of trading grazing rights and restricts who can hold federal grazing permits.

Third, federal grazing permits have generally been restricted to those operating in the livestock business. In 1995, new BLM regulations sought to eliminate this requirement. The regulations, however, were challenged in court by the livestock industry. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the BLM regulations in Public Lands Council v. Babbitt (2000), but the use-it-or-lose-it requirement effectively limits grazing permits to livestock owners.49 Therefore, while the exact requirements may have been lifted, the federal grazing system still imposes barriers to holding permits for non-grazing purposes.

These obstacles tip the scales towards raiding rather than trading as a means of influencing outcomes on the federal rangeland. This is unfortunate because, as several prominent environmental leaders have acknowledged, trading may represent the most practical and effective conservation strategy to ensure environmental protections on the federal rangeland. Andy Kerr, for example, has stated that purchasing grazing rights would be an “easier” and “more just” approach to environmental protection than traditional command-and-control strategies. Kerr has called for the federal government to buy-out western ranchers’ grazing permits and retire them. Ranchers should be compensated for the loss of their permits, rather than simply raiding them, according to Kerr, who calls the plan “a solution to an environmental problem that requires less government regulation and lets the free market work.”50

Kerr helped organize a campaign to promote buyouts as a practical solution to the legal and political battles over grazing.51 Federal rangelands often have low economic value for grazing purposes, so many environmental groups likely have sufficient resources to buy out ranchers’ permits. But even if environmentalists did not purchase grazing rights, some believe there is a strong case for the federal government to buy out ranchers. Because the costs of administering the federal grazing system are so high, and the revenues derived from those lands so low, the federal government consistently loses money managing federal lands for grazing purposes.52 Thus, some have argued that it would pay to abolish the existing grazing program and buy out all grazing rights.

To that end, Kerr helped launch the National Public Lands Grazing Campaign which promoted a Voluntary Grazing Permit Buyout Act, calling for the federal government to compensate public lands ranchers who agreed to relinquish their grazing permits for $175 per AUM.53 Under this proposal, a rancher with a permit to graze 500 cattle for five months would receive $437,500. The permits would then be retired by the federal government and managed for environmental purposes. Although the campaign has yet to succeed, it illustrates a genuine interest in resolving grazing disputes through trading and a general dissatisfaction with the traditional regulatory approach to protecting federal rangelands.

Case Studies

Despite the obstacles to trade, there have been several innovative efforts to trade as an alternative to raiding to resolve disputes over the federal rangeland. In some cases, environmental groups have successfully paid ranchers to relinquish their grazing permits to protect wildlife habitat. Others have purchased base properties and acquired the federal grazing permits attached to them, spending their own money raised from private member donations. Environmentalists have bargained with ranchers to retire federal grazing permits, compensated ranchers for losses due to wildlife, and negotiated contracts that allow wildlife to access private land during certain times of the year.54

Deals like these are the exception rather than the norm, but they represent a fundamentally different choice in the raid-or-trade calculus. They involve groups that acknowledge prior use rights and seek gains from trade. Understanding how and when these trades occur is an important first step to finding ways to lower the costs of negotiation enough to encourage more trading, and less raiding, on federal rangelands. The brief case studies that follow explore several of these examples in greater detail. They provide lessons learned for resolving range conflicts, illuminate obstacles to encourage more widespread trades, and suggest several opportunities for reform.

Grand Canyon Trust

The Grand Canyon Trust, a conservation group, has negotiated grazing buyouts with ranchers in Utah since 1996. Between 1999 and 2001, the group spent $1.5 million to purchase base properties with about 350,000 acres worth of grazing permits in and near the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.55 The group considered the properties and their associated federal grazing allotment as ecologically sensitive and important areas worthy of protection from the impacts of grazing and sought to purchase the base properties as an effective conservation strategy.

The Trust’s efforts were complicated due to the use-it-or-lose-it requirements on federal grazing lands. The grazing permit that came along with the properties required the group to graze cattle on the allotment or lose the permits. The value of the grazing permits was capitalized into the value of the base property when it was sold to the group and represented a significant financial investment on the part of the Trust. Originally, the Trust offered to relinquish the grazing permits to the BLM if the agency declared the allotments closed as part of its land use plan. But soon other ranchers applied to the BLM to have the grazing permits transferred to them instead since the Trust had no intent to graze. When that happened, the Trust decided to purchase the minimum number of cattle to graze on the allotment in order to retain control of the grazing permits.56

This case study illustrates an important lesson for promoting trading on federal rangelands: Even if grazing rights are well defined and respected, they must also be transferable to groups such as the Grand Canyon Trust. Current grazing rules, however, generally prevent ranchers from trading permits to environmental groups who do not intend to run livestock on the land. And because the base property requirement attaches grazing permits to specific ranches, the cost for environmental groups to acquire such base properties is increased if the grazing permit values are capitalized into the ranch property value.57 Such requirements clearly raise the costs of trading for groups that want to use rangelands for purposes other than grazing.

Cows, Not Condos

The use-it-or-lose-it requirement may be less of an obstacle for environmental groups that view livestock grazing as consistent with their conservation objectives. These groups can acquire base properties and use the associated grazing permits for livestock grazing under their own care and management while ensuring adequate environmental protection of the federal rangeland.

For some conservation groups, cattle grazing may be seen as a lesser of two evils—with the greater threat coming from commercial and residential development. In some cases, this has led to cooperative arrangements between environmental groups and livestock owners.58 Groups such as The Nature Conservancy (TNC) have acquired base properties along with the associated grazing permits in an effort to outbid developers on the western landscape. Groups such as TNC would rather see the land used for cattle grazing than for large-scale commercial or residential development and may even view livestock grazing as compatible with responsible range stewardship.

In 1996, TNC acquired the Dugout Ranch in Utah, just beyond the border of Canyonlands National Park, and announced that it would continue to use the ranch as a livestock operation. TNC would ensure that livestock grazing was done in a manner that was consistent with the group’s conservation objectives to promote biodiversity and preserve the scenery and other environmental assets on the associated federal rangeland. The group acknowledged that the purchase was designed in part to prevent the land from being acquired by developers.

The group’s Utah state director said the effort was meant to move “beyond the rangeland conflict and into collaborative efforts with livestock operators.”59 Moreover, “cows are better than condos. Increasingly in the West, this is the only choice we face.” Thus, in the case of The Nature Conservancy’s specific objectives—to prevent commercial and residential development and maintain certain environmental assets on the grazing allotments—cooperative buyout solutions were possible within the existing structure of the federal rangeland system.

American Prairie Reserve

Other conservation groups have been able to work within existing federal grazing policies to accomplish their conservation objectives through trading instead of raiding. As the example of the American Prairie Reserve (APR) illustrates, however, such trading can only be accomplished under specific circumstances due to the constraints of the federal grazing system.

APR is a large-scale private conservation project seeking to protect and restore the prairies of eastern Montana, an ecosystem that has long been impacted by agricultural and ranching operations. The group aims to acquire private ranches in the region along with the associated federal grazing permits to create a landscape-scale conservation area larger than Yellowstone National Park.60 In contrast to other U.S. environmental groups, APR seeks to accomplish its mission through market forces by purchasing private lands and grazing rights from ranchers, rather than through litigation or political processes. They are trading rather than raiding.

APR acquires private base properties and restores the land back to the prairie landscape that once prevailed across much of the West. Once the group acquires base properties, they often tear down ranch buildings, pull up fences, and remove the cattle herds that have dominated the landscape for the last century. In place of the cattle, APR seeks to restore the wild bison herds as well as other wildlife species. Today, APR owns or leases more than 300,000 acres in the region and maintains a herd of more than 600 genetically pure bison.

Throughout the region, federal grazing allotments are interspersed with large private ranches, often in a scattered checkerboard of land tenure. This fact can complicate landscape-scale conservation efforts, which aim to protect vast areas in which wildlife species such as bison can roam freely. The existence of federal grazing allotments means that APR must navigate the BLM’s grazing policies to accomplish their conservation objectives. In particular, the group must be able to acquire base properties and the associated grazing permits without being forced to graze cattle on the federal allotments.

APR is able to do so due to a fortunate fact of the BLM’s livestock classifications. Bison, it turns out, are considered a class of livestock under existing BLM rules. When APR acquires a base property with a public grazing allotment, the group applies to the BLM to change the class of livestock so that bison can graze the allotment instead of cattle.61 Once the BLM approves the livestock change, APR is able to maintain control over grazing allotments without being forced, as the Grand Canyon Trust was, to graze cattle on the land. APR also requests to change the allotment grazing season to year-round grazing. In many cases, APR is also permitted to remove interior fencing to manage their private lands along with the public lands as one common pasture.

The example of the American Prairie Reserve, while thus far successful, reveals a fundamental obstacle to adopting similar conservation approaches elsewhere. The use-it-or-lose-it requirement on federal grazing lands limits the type and scope of conservation work that can be accomplished through private land transactions and grazing permit transfers.

Consider how a similar group might attempt to replicate APR’s model in a place like Nevada. Suppose that instead of protecting bison habitat the group sought to create a landscape-scale conservation project to protect desert tortoises. Not content to use lawsuits or political means to achieve their goals, the group would purchase private ranches and leverage the associated public grazing rights to protect tortoise habitat. Under current grazing rules, however—specifically the requirement to graze livestock or lose the permit—a private conservation project such as this would likely not be possible. While in APR’s case, bison can be considered livestock, a conservation group in Nevada would have a much more difficult time making the case that desert tortoises qualify as livestock.

The APR model is feasible within the existing federal grazing system, but it is unlikely that this approach is scalable to other regions or other species. Given their particular interest in bison conservation, a group like APR may view trading as a practical and attractive alternative to raiding through political or legal means to influence federal rangeland management, but the ability of other groups to utilize similar trading mechanisms in other contexts is limited or nonexistent.

Gila and Yellowstone Buyouts

Despite these obstacles, voluntary grazing permit buyouts have occurred on a limited basis across the western United States. Conservation groups such as the Conservation Fund, Grand Canyon Trust, Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep Association, the National Wildlife Federation, and the Oregon Natural Desert Association have purchased—that is, traded for—grazing permits from ranchers and sought to retire them.62 Such efforts are costly and tenuous. They are able to occur only on a case-by-case basis and at high transaction costs. Yet buyouts are increasingly seen as a practical way to achieve conservation outcomes on federal rangelands.

Once a group buys a rancher’s grazing permit, they often request that the federal land agency retire the grazing permit. This requires that the BLM or Forest Service agree to formally change the area’s management plan to cancel grazing on the allotment. Even if conservation groups can convince the federal land agencies to retire permits they have acquired, the retirements are not guaranteed, nor are they permanent. The area management plans come up for revision every 10 or 15 years, in which case the agencies could re-open the allotments for grazing. Only Congress can permanently retire a grazing permit.

Wild Earth Guardians, a nonprofit environmental organization, is pursuing the voluntary buyout strategy to protect grazing allotments in the Gila National Forests in New Mexico. According to Bryan Bird, one of the group’s directors, the strategy represents “a free-market approach” to the longstanding confrontation between environmental groups and ranchers. “We’re trying to provide a viable opportunity for grazing permittees to voluntarily sell their permit,” says Bird.63 The group views the buyout approach as a practical means of resolving land-use conflicts, particularly with the reintroduction of Mexican gray wolves in the region in 1998. The wolves, a protected species, often kill livestock and create acrimony between ranchers and conservationists.64

The Wild Earth Guardian’s buyout program works as follows: The group negotiates a private agreement with a rancher to acquire their grazing permit. Wild Earth Guardians then approaches the Forest Service to request retirement of the grazing allotment. The Forest Service evaluates the proposal and decides what to do with the grazing permit. Wild Earth Guardians does not own the grazing permit.

This is a tenuous process. The Forest Service has traditionally been reluctant to retire allotments. Wild Earth Guardians acknowledges that the agency could simply issue the grazing permit to another rancher—a function of the use-it-or-lose-it principle governing federal rangeland management. In at least one case, however, Forest Service officials with the Gila National Forest have been willing to approve temporary grazing retirements of grazing permits purchased by Wild Earth Guardians.65 So far, the group has reached only one buyout deal with a rancher in the region, but it has reportedly received interest from several other ranchers.

Elsewhere in the United States, environmental groups have pursued similar buyout strategies to resolve livestock-wildlife conflicts. Since 2002, the National Wildlife Federation has secured more than half a million acres of federal grazing land outside Yellowstone National Park to protect habitat for bison, grizzly bears, and wolves. The group does so by negotiating voluntary buyouts with ranchers and relying on federal land agencies to retire the allotments. Rick Jarrett, a Montana rancher, had a permit to graze cattle on 8,000 acres in the Gallatin National Forest, but his livestock operation was increasingly threatened by growing populations of grizzly bears and wolves—both federally protected species. “I was looking for solutions, not playing politics,” Jarrett said after reaching a deal to sell his permit to the National Wildlife Federation. “I guess that’s why it worked so well.”66 The Forest Service, in this case, agreed to retire the grazing permit to alleviate the wildlife conflicts on the allotment.

Concerns from Ranchers

Trading solutions such as the ones described above, however, are not without their critics. Legal disputes from livestock associations have challenged the ability of environmental groups to acquire base properties without the intent to graze. Several of the cases described above are controversial among local ranchers and ranching communities concerned with the decline of traditional rural life. Moreover, ranchers often view the emergence of environmental values on the federal rangeland as a threat—even when its goals are accomplished through trading instead of raiding.

In the mid-1990s, the BLM attempted to establish “conservation permits” that would allow grazing permits to be used for non-grazing conservation purposes for up to 10 years. However, the proposal was met with considerable opposition from ranchers and was ultimately ruled against by the courts.67 Even efforts by groups such as the American Prairie Reserve, which seek to purchase private ranches at market value, are often controversial among local residents who are skeptical of the conservation group’s agenda and wary of efforts to remove cattle from the landscape.

Part of the opposition to these trading solutions comes from the effect of simultaneous “raiding” strategies pursued by many other environmental groups to influence federal rangeland management. While organizations such as American Prairie Reserve and Grand Canyon Trust may pursue honest bargains, ranchers are often simultaneously threatened by legal and political actions aimed at reducing their ability to access federal rangelands. Trading solutions such as the ones described above often occur under the backdrop of a broader federal environmental regulatory landscape that is often threatening to ranchers. Endangered species policies, for instance, may undermine their ability to protect their livestock from harm. Federal land policies may gradually reduce their grazing privileges to protect environmental resources. These forces contribute to the common perception among ranchers that they are being regulated off their land and that their livelihoods are at risk.

Thus, some ranchers believe that grazing buyouts and other “trading” approaches are merely a final blow to ranchers whose livelihoods have already been squeezed by regulations that are, in effect, kicking them off the federal rangeland. Regulations force ranchers into becoming willing sellers by devaluing their ranching operations to the point where there is no feasible alternative other than to sell. The value of ranchers’ base properties are significantly affected by such regulatory approaches, thus making buyouts more feasible for conservation groups to eventually purchase once ranching operations become unprofitable. Federal designations such as national monuments have made it more difficult for ranchers to operate in many regions, and increasing recreational demands for federal grazing allotments have posed additional challenges for grazing permittees.68

As these concerns suggest, raiding still prevails over trading on the western rangeland. However, the case studies cited above suggest that the trading approach is a viable—and often preferred—strategy to address rangeland conflicts. Several groups such the American Prairie Reserve view trading as a superior approach to accomplishing their preferred environmental outcomes. Moreover, these examples help identify several grazing policy reforms that, if addressed by policymakers, could encourage less raiding and more trading in the federal grazing system.

Conclusion

At least in theory, ranchers could stand to benefit from allowing trades with environmental groups to occur. A study of federal grazing permits by economists Myles Watts and Lorraine Egan in 1998 found that as the value of the federal rangeland has increased along with new and evolving demands for environmental uses, grazing permit values have declined.69 This result, however, is seemingly backwards. Increased rangeland value should cause grazing permit values to increase, yet that is not the result observed in the West today.70

“If the rights to grazing permits were secure and transferable,” Watts and Egan explain, “then grazing permit values would not decrease in value as noncommercial uses become more desired.” In fact, the opposite would happen. Permits would become more valuable as competing groups bargained for gains from trade. However, since grazing rights cannot be traded in market institutions based on property rights, they are liable to be raided through political institutions, casting uncertainty on their value today.

In order for trading to prevail over raiding on the federal rangeland and elsewhere, groups must be prevented from simply raiding to achieve what they want at minimal cost. That is, the relative cost of trading needs to decrease and the relative cost of raiding increase to encourage more trading and less raiding. In today’s federal grazing system, environmental litigators benefit from the raiding approach. In many cases, the federal government encourages litigation through the Equal Access to Justice Act, which often pays the legal fees of environmental groups in successful suits brought against the federal government.71 Any attempt to promote trading must also reduce the regulatory power for environmental groups to regulate, litigate, or otherwise raid.

At the same time, more policy reforms are needed to lower the transaction costs among competing groups for federal rangeland resources. Reforms are needed to accommodate a host of different values, including non-grazing environmental values, and permits should be recognized as secure and transferable property rights. Moreover, grazing permits should be allowed to migrate to their highest-valued use, whether that is cattle grazing or tortoise habitat. This suggests that federal rangeland policy should be reformed to eliminate the base property requirements, the use-it-or-lose-it requirement, and the requirement that grazing permit holders must be in the business of grazing livestock.

It is clear that today’s federal grazing institutions promote far too much raiding and not enough trading. As the Bundy standoff demonstrated, conflicts over land use have the potential to erupt into full-scale range wars. The raid-or-trade model provides a clear lesson for policymakers in the United States and elsewhere: If property rights are well-defined, enforced, and transferable, then disputes among competing users are more likely to get resolved peacefully, cooperatively, and in a mutually beneficial manner. Finding ways to strengthen property rights, even in the context of existing federal rangeland policy, would go a long way to encouraging more trading and less raiding on public rangelands.

Download the full report, including endnotes and references.