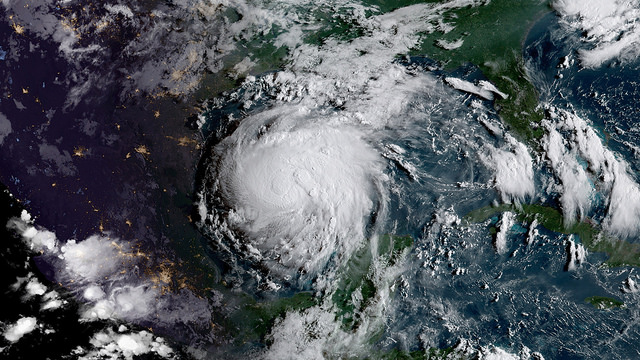

Hurricane Harvey has wreaked historic levels of devastation on the Gulf Coast. The storm damaged an estimated 150,000 properties and dumped more than 51 inches of rain on southeastern Texas since it made landfall on August 25.

The hurricane has also brought renewed attention to a federal policy that’s set to expire at the end of September: the National Flood Insurance Program. The program is commonly the only form of flood insurance covering homeowners in coastal areas. Critics of the NFIP contend that it provides perverse incentives for people to build—and rebuild—in flood-prone areas, and at significant taxpayer expense. One home in the Houston area, for instance, has been awarded more than $1.8 million through the NFIP for repeated rebuilds—nearly 16 times the structure’s estimated value of $116,000.

We asked economist Kerry Smith, an expert on the National Flood Insurance Program, about issues with the program in light of Harvey and its impact. Smith is an emeritus professor of economics at the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University and a 2017 PERC Julian Simon Fellow. His responses are below.

Q: How does the National Flood Insurance Program distort incentives for homeowners?

A: Established in 1968, the National Flood Insurance Program had three objectives: to ensure affordable insurance, to promote widespread participation in the program, and to earn sufficient premium and fee revenue to cover claims and expenses. Currently, the program creates flood insurance rate maps (FIRMs) that are the basis for the rates charged for insurance. The maximum insurance coverage for private homes is $250,000 for the structure and $100,000 for the contents.

Any insurance pricing structure that is not based on the risks associated with a home in a given location creates distorted incentives. Homeowners living in those locations would be led to believe their locations face lower risks of hazards than what is really anticipated. Prior to the passage of the Biggert-Waters legislation in 2012, the NFIP offered three categories of coverage at below-risk rates. These coverages were offered for pre-FIRM properties, grandfathered properties, and properties in communities participating in the Community Rating System.

Properties designated as pre-FIRM were built before FEMA mapped the flood risks in their location. As a result, the insurance rates charged for these properties faced are not based on the risks identified in FEMA maps. Pre-FIRM rates also do not have an adjustment for the height of the first floor of a building in relationship to the base flood elevation levels. These factors result in rate subsidies for these properties; however, the subsidized rates apply only to the basic limit of the policy, the first $60,000 of coverage. Grandfathered properties are homes that were built in compliance with the FEMA hazard maps as they were drawn at the time of construction. These properties are allowed to maintain lower rates for insurance even if an updated map results in a home moving into a higher-risk flood zone. Community Rating System subsidies offer policyholders discounts from 5 to 45 percent if their communities adopt various risk-mitigation policies.

The Biggert-Waters legislation was intended to allow the NFIP to follow actuarial pricing principles. To implement the policy, the program established revenue targets based on historical average loss year. The legislation phased out this approach, and a 2015 National Research Council report estimated it could have led to a significant increase in premiums for 20 percent of the policies with flood insurance. But homeowners in coastal areas reacted negatively to the proposed changes. As a result, Congress passed the Homeowners Flood Insurance Affordability Act in 2014, which reinstated grandfathered rates and allowed the pre-FIRM subsidized premiums to rise to risk-based levels gradually rather than quickly. California, Texas, New York, and Florida have the largest number of pre-FIRM subsidized policies.

Q: Is there a line to be drawn between the NFIP and the outcomes of such storms in terms of the effects the policy has incentivizing people to live in flood-prone areas and the results when tragic storms hit?

A: No. Many different policies indirectly create subsidies for those living in risk-prone coastal areas. For example, Kousky, Michel-Kerjan, and Rashkey have found that disaster assistance after a hurricane appears to reduce homeowners’ incentives to purchase insurance. In the case of Florida, they found that when a storm is declared a presidential disaster, federal aid that provides grants, subsidized loans, and other funds to return communities to their pre-disaster conditions results in reductions in average insurance coverage. Thus, homeowners purchase less insurance to prepare for the next storm. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s 2017 report on the NFIP, four states had the largest estimates for anticipated gross losses from storm surges and hurricane-related precipitation—Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and South Carolina. This analysis suggests that storm-related damage can be anticipated. To the extent insurance rates do not signal the anticipated risk of damage, policy contributes to the problem. The CBO report also found that coastal counties account for 10 percent of the NFIP policies and 75 percent of the expected claims. According to this report, coastal counties in Texas generally paid less in flood insurance premiums than their anticipated claims, and the counties affected by Harvey are among those with the largest anticipated claims even before the hurricane.

Q: The NFIP is already nearly $25 billion in debt. How might Harvey impact the program?

A: Current NFIP debt cannot be repaid with the current rate structure. The CBO report cited above estimates that the program can be expected to lose $700 million a year (excluding the costs of mapping floodplains and costs of efforts to mitigate flood risk, as well as the interest on its existing debt). Hurricane Harvey is likely to lead to significant losses that exceed the NFIP’s borrowing capacity from the U.S. Treasury. As a result, any new legislation renewing this program will have to deal with existing debt as well as the losses from Harvey. The Wall Street Journal reports that there were approximately 400,000 flood insurance policies in effect in the impacted counties in Texas.

Q: The program is set to expire at the end of September. What’s ahead for the NFIP? Are there changes to it on the horizon?

A: There are two sets of legislation being considered for renewing the NFIP. The House bill would require the program to reduce the liability that U.S. taxpayers face by exploring ways to spread the risk through what are referred to as “risk transfer tools” such as reinsurance, catastrophe bonds, insurance-linked securities, and other options. It also proposes to reduce excessive claims and eliminate the availability of NFIP insurance for multiple-loss properties. It continues to give attention to affordability but is not as specific as a comparable Senate bill.

The House bill also calls for a pilot program to purchase properties from low-income owners who have experienced substantial damage from floods. This would arise only when judged to be cost effective, and the information on the pilot program has many qualifications. The main objective is to repurpose the lands for conservation or recreation so they are no longer subject to storm-related risks. The legislation also encourages mitigation. Both the House and Senate bills address issues associated with enhancing the processes involved in handling flood damage claims.

Neither set of legislation appears to address the issue of aligning insurance rates with actual risks. The information on the Senate bill highlights improvements in flood mapping, enhanced databases and maps for storm-related risks, extension of private insurance coverage, and promotion of mitigation. But it preserves grandfathering and creates new subsidies that appear focused on continuing the emphasis on affordability. It would be naïve to think the experience with Hurricane Harvey will not lead to significant changes in the NFIP, but it also seems reasonable to believe they will not be directed at insurance rates that reflect the risks faced by those living in coastal areas.

Q: Outside of coastal homeowners, what interest groups have the largest stakes in the status quo of the NFIP?

A: U.S. taxpayers have two reasons to be concerned about the NFIP. First, under the current system, taxpayers hold the default liability for the insurance the program provides and have little direct say in the pricing decisions for the insurance. Second, there may well be reasons to expect continued increases in economic activity in coastal areas, and those decisions are not being informed by insurance rates that reflect actuarially based risks. The 2016 update to the State of the U.S. Ocean and Coastal Economy Report reveals that shore-adjacent states grew by about one tenth of one percent faster than the U.S. average. To the extent severe storms damage these areas and affect a large fraction of overall economic activity concentrated in coastal areas, then the impacts on the overall economy seem likely to become more pronounced as both the concentration of activity and the severity of storms increase.

Q: If you could wave a wand and make any changes to the existing NFIP, what would you do?

A: Eliminating subsidies overnight is politically infeasible. The subsidized rates do need to be phased out—both pre-FIRM rates and grandfathered ones. We need a policy that can be maintained because the situation is only going to get worse and the inherent value of these place-based rents grow as risks grow. In addition, affordability standards cannot be set independent of the income and wealth status of homeowners who seek NFIP insurance.

A record of continued losses and claims requires policies that promote migration away from high-risk areas. One possibility is that NFIP insurance could be denied for properties owned by high-income households (who would instead rely on private insurance), and plans to purchase properties from low-income households so areas can be abandoned should also be evaluated as a cost-effective response in high-risk areas.

References

Committee on the Affordability of National Flood Insurance Program Premiums, National Research Council. 2015. Affordability of National Flood Insurance Program Premiums: Report 1 (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press).

Congressional Budget Office. 2017. The National Flood Insurance Program: Financial Soundness and Affordability, September.

Emanuel, Kerry. 2005. “Increasing Destructiveness of Tropical Cyclones Over the Past Thirty Years.” Nature, 436(4):686-688.

Ip, Greg. 2017. “Insuring Coastal Cities Against Next Hurricane Harvey.” The Wall Street Journal, September 1.

Kousky, Carolyn, Erwann O. Michel-Kerjan, and Paul A. Raschky. 2017. “Does Federal Disaster Assistance Crowd Out Private Demand for Insurance?” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, forthcoming.

National Ocean Economies Program. 2016. State of the U.S. Ocean and Coastal Economies, Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey.

Strobl, Eric. 2011. “The Economic Growth Impact of Hurricanes: Evidence from U.S. Coastal Counties.” Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (2): 575-58.