The management of the lesser prairie chicken is a controversial topic with widespread implications for land use and energy development across several western states. The bird’s population declined in the mid-20th century as native landscapes in the southern Great Plains were converted to agriculture. Populations of lesser prairie chickens have shown modest increases in recent years, but resource development and habitat degradation continue to threaten the species’ habitat. In 2014, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) listed the bird as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, but the listing was voided a year later when a federal court in Texas ruled that the agency failed to properly take into consideration state and private conservation efforts. Today, the lesser prairie chicken is once again “under review” to be re-listed.

A unique alliance of wildlife agencies, conservation organizations, private landowners, and industry partners have collaborated to help recover the lesser prairie chicken while preserving traditional land uses. In Kansas, the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA), Pheasants Forever, and ranch manager Tom Hammond joined together to create an innovative approach to achieve this goal. The first of its kind, the arrangement ensures Hammond’s ranch is managed to provide lesser prairie chicken habitat into perpetuity while allowing continued historical uses of the land, such as cattle grazing. This voluntary, proactive approach to species conservation is now being replicated throughout the lesser prairie chicken’s existing range and could also be adopted for other species in need of recovery.

The Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 was designed to protect imperiled species from extinction. Under the act, species can be listed as endangered or threatened, depending on whether they are in danger of extinction or are likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future. The USFWS is responsible for administering the protection of listed terrestrial species, while the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is responsible for marine species.

There are no specific numerical, percentage, or scientific standards, however, for listing or delisting a species. There are currently more than 2,000 species protected under the Endangered Species Act, yet in more than 40 years of protections, fewer than 1.5 percent of endangered species have been recovered and delisted. These poor results come with a lofty price tag—in 2014 the federal government spent nearly $1.5 billion to protect listed species.

Not only does the Endangered Species Act lead to large public expenditures that recover very few species, but it can also cost private landowners the use of their land. Section 9 of the act includes a clause that prohibits the “taking” of an endangered or threatened species. In this context, “take” has been defined as “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” This definition was later expanded so that habitat degradation is also considered a taking; therefore, if a landowner’s property is designated critical habitat under the Endangered Species Act, the owner could face restrictions on land uses that could theoretically degrade the habitat, even if no endangered species has taken up residence on the land. As a result, traditional land uses such as grazing livestock, cutting trees, using water sources, or building structures can be restricted.

In 2014, when the lesser prairie chicken was under consideration for an endangered-species listing, WAFWA officials in Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas jointly developed a range-wide conservation plan, approved by the federal government, to protect the species through voluntary conservation efforts. Their aim was to prevent the listing of the species and the harm to landowners, ranchers, and energy developers that would follow. Enrollees in the range-wide plan, largely oil and gas developers, committed to minimize disturbances to the bird and provide funding for private conservation efforts. In return, they were provided certain protections against punishment for lesser prairie chicken takings.

Nevertheless, in April 2014, the lesser prairie chicken was listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. The Permian Basin Petroleum Association and several New Mexico counties filed a lawsuit challenging the listing. In September 2015, a federal court in Texas ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, vacating the final listing rule. The judge vacated the ruling on the procedural grounds that the USFWS did not adequately consider the future benefits of WAFWA’s conservation plan.

In July 2016, the USFWS fulfilled the court ruling and removed the lesser prairie chicken from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife. Less than six months later, however, there were already petitions under review to re-list the bird, which is currently considered a candidate species for listing.

The Lesser Prairie Chicken

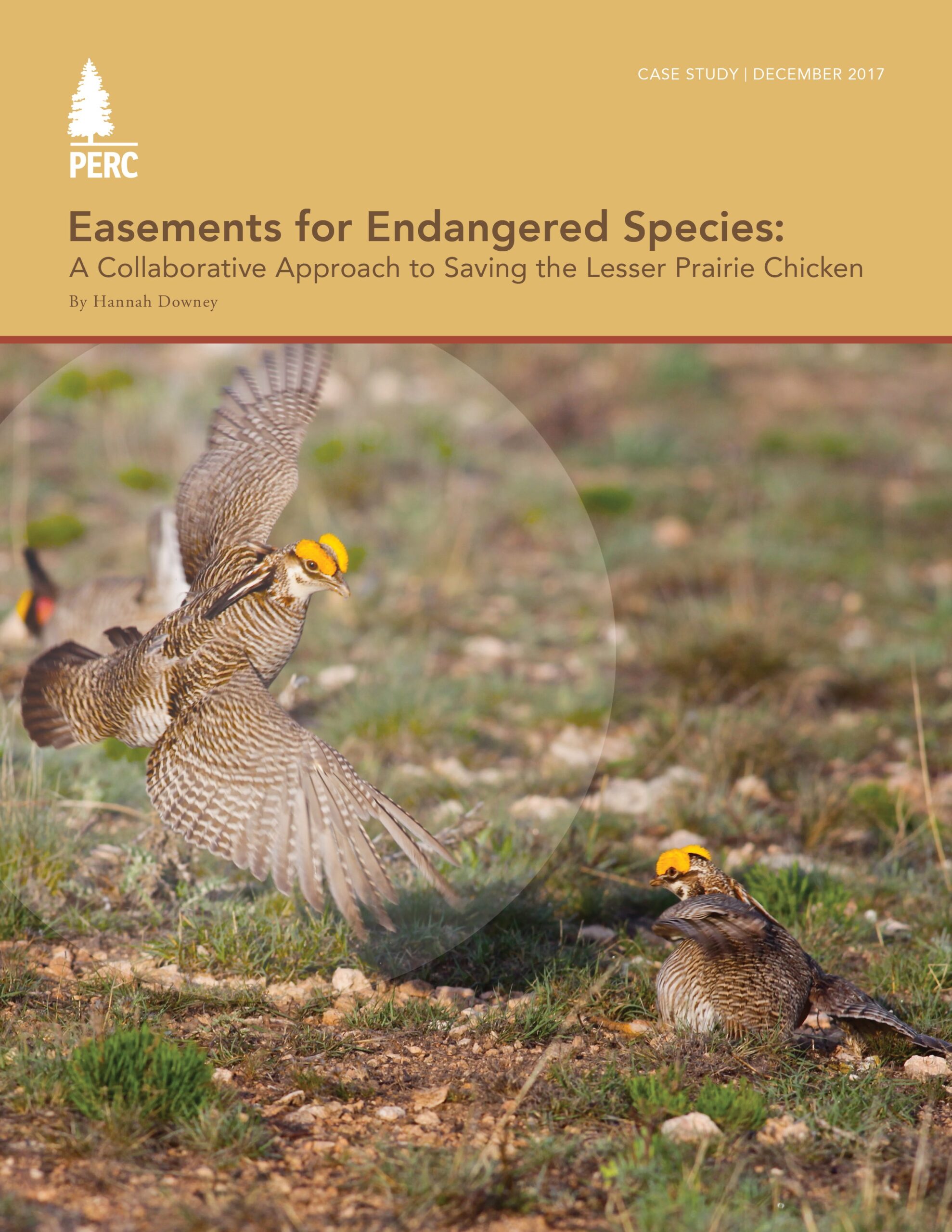

The lesser prairie chicken is a medium-sized grouse found in the southern Great Plains, including Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. The bird is found in native and restored grasslands that are scattered with shrubs.

The lesser prairie chicken needs three categories of habitat in close proximity to maintain sustainable populations. Nesting habitat requires native vegetation about a foot tall. Sand sagebrush and shinnery oak provide important structure for nesting habitat in some areas of the animal’s range. Brood habitat consists of native forbs and bare ground that make it easy for chicks to find insects and other food. Lekking habitat, where the birds display their elaborate courtship rituals, are usually located on hilltops or slight rises with thin vegetation and good visibility so that females can see males’ best efforts at attracting a mate.

During the spring mating season, females lay between eight and 13 eggs per clutch. Typically, about 30 percent of clutches produce at least one chick, with the average size of the brood being about five chicks. The likelihood of chicks making it to adulthood largely depends on the quality of habitat available to them as well as weather conditions.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that the lesser prairie chicken has lost 84 percent of its habitat across its historical range. This is significant because the bird serves as a key indicator species of the health of native grasslands that support local communities and wildlife.

Currently, the highest densities of lesser prairie chickens are in northwestern Kansas. These populations are supported primarily by grasslands that were restored through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Conservation Reserve Program. The birds were originally thought to have been extirpated from areas north of the Arkansas River, including this section of Kansas, in the 1960s. But the birds reappeared in those areas in the early 1990s, shortly after the initial Conservation Reserve Program plantings became established. The region has since grown to become the stronghold for the species it is today.

WAFWA and the Range-Wide Plan

The Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Associations is composed of representatives from 19 state fish and wildlife management agencies and represents nearly 3.7 million square miles of North America. The association supports resource management and partnerships to conserve native wildlife. It also developed and administers the conservation plan for the lesser prairie chicken across the southern Great Plains. The agencies observed the decline of the bird and its habitat and were aware of how an endangered or threatened listing of the lesser prairie chicken could impose land-use restrictions on property owners.

With ties to states and local communities, WAFWA wanted to develop a conservation plan for the lesser prairie chicken that would find ways to protect the species in some areas while also allowing landowners to continue farming, ranching, and developing resources on their land without the risk of being charged with an incidental taking of the bird. To do so, WAFWA developed the Lesser Prairie Chicken Range-Wide Plan in 2013, prior to the bird’s listing as a threatened species. The goal of the plan was to coordinate with parties involved in the bird’s survival to conserve habitat and reboot lesser prairie chicken populations to a point where the bird would be plentiful enough to avoid endangered-species protection.

An interstate WAFWA working group, composed of wildlife officials from the five states where the bird is found, wrote the Range-Wide Plan. The plan establishes population and habitat goals for all agencies and organizations working with the species, and it provides a mechanism for industry and agriculture to continue operating. The plan brings together different voluntary conservation programs in a common approach to provide for conservation of lesser prairie chicken habitat and minimization and mitigation of impacts to ranch and oil and gas operations. Specifically, it outlines a partnership between the five range states, industry partners (including oil, gas, wind, electricity, and telecommunications companies), and private landowners (mainly farmers and ranchers).

Under Rule 4(d) of the Endangered Species Act, the USFWS has the discretion to exempt some actions from the act’s take prohibition. The Range-Wide Plan was established in accordance with Rule 4(d) to develop a conservation strategy for the lesser prairie chicken that identifies, coordinates, and commits to the restoration of habitat for the species throughout its current or extended range. The plan was endorsed by the USFWS in September of 2013 and was codified when the rule was finalized in 2014, protecting groups that enrolled in the plan and engaged in efforts to preserve the lesser prairie chicken from facing punishment for incidental takings of the species. The Range-Wide Plan was created prior to the listing in an effort to help grow the bird’s populations to a point where it did not warrant listing and so that, in the event of a listing, landowners would have some protection against the take prohibition.

Oil and Gas Industry

The oil and gas industry is a major player in the Great Plains. Energy developers knew that the listing of the lesser prairie chicken concerned local farming and ranching communities, and they thought WAFWA’s record of using state expertise and an innovative approach to protecting the bird’s populations merited their support.

They also had a direct incentive to enroll in the Range-Wide Plan because it includes a Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances for oil and gas enrollees. The agreement ensures that if an enrolled company enacts specified procedures to limit the harm their operations cause the lesser prairie chicken, then they are protected from being charged if they harm one of the birds or its habitat. Given that energy development plays a large economic role in the same area that the lesser prairie chicken calls home, the plan meant that energy developers had a way to continue their work even if it threatened the species’ habitat. If the lesser prairie chicken was listed and they were not enrolled, their operations would be limited to areas not considered to be habitat for the bird. In effect, if the bird were listed, it would have become exceptionally difficult for oil and gas companies to operate in the southern Great Plains.

Under the Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances component of the Range-Wide Plan, oil and gas industry partners agree to voluntarily commit to operating in ways that remove or reduce threats to the lesser prairie chicken so that re-listing will not be necessary. These include avoiding non-emergency operations during early mornings of the breeding season, avoiding off-road travel in potential nesting habitat during the breeding season, installing escape ramps in open water tanks, marking fences to prevent lesser prairie chickens from flying into them, and burying electric lines in key breeding areas.

Companies are required under the Range-Wide Plan to pay impact fees before they harm habitat, and WAFWA must commit those funds to conservation efforts by farmers and ranchers before construction begins. For example, a 5-acre pad may require a fee for up to 31 acres depending on how much of that area has been previously impacted by development. The fees are established based on the actual cost of restoring and maintaining twice as much habitat as impacted by the development at an equal or better habitat quality. Enrollment fees may be used by the companies as prepaid impact fees until they are exhausted. Afterward companies must pay more impact fees as needed. All impact fees are placed in the same conservation trust as enrollment fees. The interest from that trust pays farmers and ranchers to restore and manage lesser prairie chicken habitat in perpetuity.

Enrolling industry lands in the conservation agreement costs only $6.75 per acre for oil and gas or wind projects. Other types of developers are charged a flat fee ranging from $5,000 per year for electric distribution to $20,000 for transmission. These enrollment fees are used to generate conservation credits before the companies begin development, and 87.5 percent of enrollment-fee revenues are placed in a trust to fund conservation offsets for private landowners. Since WAFWA began the Range-Wide Plan four years ago, it has authorized more than 1,000 industry projects, with mitigation fees paid for nearly 750 of those projects. The companies that developed the remaining projects avoided and minimized enough impacts to preclude the need for mitigation.

The oil and gas companies that enroll in the Range-Wide Plan receive a 30-year permit from the USFWS that allows them to continue their work while being protected from incidental takings. If development lasts longer, the company must work with WAFWA to receive an extension.

This approach to involving resource-development companies in the conservation of the lesser prairie chicken has been welcomed by the companies. More than 170 industry partners have enrolled, and WAFWA has collected more than $63 million in enrollment and mitigation fees that support conservation activities for the bird.

WAFWA’s plan has allowed for economic development by providing a mechanism for groups to voluntarily conserve lesser prairie chicken habitat in compliance with the Endangered Species Act while still using the land for development.

Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever

Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever are groups of sportsmen and conservationists dedicated to the preservation of pheasants, quail, and other wildlife through habitat improvements, public awareness, education, and land management policies and programs. Both organizations have reputations for working with landowners and other organizations on projects that conserve wildlife habitat. Because valuable habitat is often found on private working lands, these groups partner with landowners to enhance, restore, and protect the habitat on these lands in harmony with traditional uses.

Managing the lesser prairie chicken’s habitat requires a landscape-level approach focused on large native grasslands, which overlaps with the habitat requirements for pheasants and quail. This made it a natural fit for Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever to take up lesser prairie chicken habitat conservation because the efforts would also benefit their species of interest.

With the money available from industry partners’ enrollment, WAFWA partnered with Pheasants Forever to purchase and hold easements. The partnership was effective because WAFWA had the funds needed to purchase easements, and Pheasants Forever had the experience holding and overseeing easements designed to protect wildlife.

The Ranch

WAFWA has committed to generating 25 percent of their mitigation efforts through permanent conservation agreements. Though WAFWA had some experience with short-term management agreements with ranchers, they had never entered into a permanent conservation easement. Some ranchers are reluctant to agree to permanent conservation agreements because they want greater flexibility down the road in managing their ranches to respond to changing uses of the land. Yet WAFWA was determined that permanent conservation was vital to the survival of the lesser prairie chicken and searched for a rancher with a dedication to wildlife conservation and a willingness to do so into perpetuity.

Tom Hammond co-owns and manages a ranch in southern Kansas that fit the bill. He runs between 100 to 150 head of cattle on the ranch and expressed an interest in conserving wildlife habitat as well. Hammond and his ranch co-owners were interested in conserving endangered species while respecting the historic use of the land. They expressed interest in the WAFWA conservation easement program for the lesser prairie chicken, putting an innovative approach to endangered-species protection in motion.

Part 1: Kicking Things Off

With money and a goal established by the Range-Wide Plan, WAFWA was looking for landowners to engage in permanent conservation easements for lesser prairie chicken habitat. WAFWA and Pheasants Forever were familiar with the ranch Hammond managed and knew his track record for conservation, so when he and the other ranch owners expressed interest in negotiating a conservation easement on the property, all parties were optimistic.

In the Range-Wide Plan, WAFWA had created a ranking system to assess the value of potential permanent conservation sites for lesser prairie chicken restoration, and Hammond’s ranch scored top marks. The ranch lies within one of the highest-priority areas for lesser prairie chicken conservation, home to all three types of the bird’s habitat. To make matters even better, the property and the surrounding area included a few lek locations where lesser prairie chickens were known to breed. WAFWA knew the property was managed with a strict stewardship ethic, and they hoped to put a permanent conservation easement on the property to ensure that management approach continued into perpetuity.

With Pheasants Forever onboard to hold the easement, it and WAFWA began to negotiate an arrangement with Hammond in 2015. In addition to the easement, the parties also had to agree on a dynamic-management plan that outlined how to comply with the easement, which would also be implemented in perpetuity.

Establishing a permanent conservation easement on a property and requiring specific management approaches through the accompanying management agreement comes at a cost to the landowner. It was estimated that enacting the easement would decrease the market value of Hammond’s ranch by 25 percent. To compensate for this loss, WAFWA used the funding available from Range-Wide Plan enrollments to make a one-time payment to the landowners equal to the amount of the appraised value lost. It also set up an endowment to fund the perpetual management agreement. By grazing fewer cattle and engaging in conservation habits outlined in the agreement, Hammond forgoes some potential profit every year. The endowment provides him with an annual payment to make up this difference as long as he abides by the management agreement.

It took over a year and a half to hammer out the details of the easement and management agreement, but in December 2016, WAFWA, Pheasants Forever, and the landowners reached an agreement.

Part II: The Details of the Arrangement

A permanent easement to conserve nearly 2,000 acres of high-quality lesser prairie chicken habitat on a ranch in south-central Kansas represented a major victory. While WAFWA pays for the easement and management plan, Pheasants Forever holds and monitors the easement. The arrangement is the first permanent conservation easement with a private landowner secured as a part of the Range-Wide Plan.

The conserved land is all native rangeland historically managed for livestock production. While the easement legally restricts future developments and activities that would be detrimental to lesser prairie chicken habitat, all other property rights associated with the historical use of the land are retained by Hammond. The property remains a working ranch, Hammond just has to manage it within the plan established with the easement.

Under the management plan, Hammond has a target total utilization rate of 33 percent for livestock grazing. He has historically run cattle at a grazing rate close to this goal because he wanted to preserve the rangeland, but many other area ranchers run at about a 50-percent total-utilization rate. The management plan also set a goal of maintaining a healthy, native rangeland providing foliar cover of more than 45 percent with no trees.

Part III: Goals

The goal of the easement is to conserve and grow key habitat for the lesser prairie chicken. WAFWA does not set population goals for specific properties because it is impossible to tie population responses to an individual property. However, it does prescribe specific management practices that aim to create ideal lesser prairie chicken habitat. Those practices include the 33-percent grazing rate and periodic prescribed fire. The strategy is that by creating better habitat for the lesser prairie chicken, which is incredibly difficult to survey, the bird population will also increase.

WAFWA plans to continue using this same innovative approach to permanently conserve additional properties for the benefit of lesser prairie chickens. The lessons learned in creating this first easement will be applied to new properties to help streamline the process. However, landowners will still have the freedom and flexibility to tailor agreements to meet their specific needs.

Ultimately, time will tell as to the success of the Range-Wide Plan and conservation easements in protecting the lesser prairie chicken. There are many changing variables that can threaten their success regardless of the successful implementation of conservation practices—primarily weather. The expansion of the program is crucial to a shot at success, but all parties involved are hopeful that birds will be free to grow their populations as habitat is conserved.

An Innovative Approach

A conservation easement funded by private-industry dollars and managed into perpetuity for the benefit of the lesser prairie chicken is an innovative approach. This project is a four-way collaboration between a wide range of partners who are not normally grouped together. Energy developers, conservation groups, state agencies, and the owners of working lands are all coming together to try to enhance lesser prairie chicken habitat. Though their motives may vary, they are able to come together around a common goal.

Unlike some traditional approaches that impose limitations on land use in the name of species conservation without compensation, this approach respects the historic use of the land while rewarding the landowner for looking out for the lesser prairie chicken. It helps ensure conservation actions are implemented long into the future because endowed funds are released annually based on the current condition of the property.

The Range-Wide Plan and easement approach also emphasize working with landowners and ranching communities—the people who interact with the species on the ground every day. The landowner has the opportunity to tailor an arrangement to his specific property, while financial compensation makes it worthwhile for landowners to adopt conservation techniques even if they result in lower profits from ranching. In addition, the landowner maintains authority over the land, making him more prone to work with conservation agencies and groups.

The involvement of state wildlife agencies provides expertise from those that are most familiar with the species and their habitat. State wildlife agencies also have established trust with local communities, making landowners more likely to work with a state agency than a distant federal agency.

As we continue to face challenges in protecting at-risk wildlife, it is important to consider innovative approaches that reward conservation efforts. The arrangement between Tom Hammond, WAFWA, Pheasants Forever, and the oil and gas industry is a powerful example of how a wide variety of groups can come together with a shared goal of protecting an at-risk species.

To view the endnotes and references, please see the entire case study here (PDF).