Prepared Statement before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources’ Subcommittee on National Parks’ hearing on S. 3172, the Restore Our Parks Act, on July 11, 2018.

Main Points

- Conservation is about preserving and maintaining what you already own. Yet today our national parks face an $11.6 billion backlog in deferred maintenance, an amount that is four times larger than the National Park Service’s latest budget.

- The deferred maintenance backlog is a big problem in need of creative solutions. Previous efforts to reduce the backlog have been inconsistent and have made only modest progress.

- The Restore Our Parks Act would make meaningful progress toward addressing deferred maintenance needs in national parks. The act would create the National Park Service Legacy Restoration Fund, a dedicated, reliable fund for deferred maintenance not dependent on annual appropriations from Congress.

- The creation of the Legacy Restoration Fund is a positive step toward addressing critical deferred maintenance needs. To comprehensively address the deferred maintenance problem, Congress and the National Park Service must also address the underlying problem of adequately funding the cyclic, ongoing maintenance that is necessary to prevent projects from becoming deferred in the first place.

Introduction

Mr. Chairman and members of the subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony on the future of our national parks and solutions to the National Park Service’s deferred maintenance backlog. My name is Holly Fretwell, and I am a research fellow and the director of outreach at the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) in Bozeman, Montana, where I have studied public lands for more than two decades. PERC is the nation’s leading institute dedicated to exploring market-based, entrepreneurial solutions to environmental challenges.

Living in Bozeman, Montana, I am lucky to have Yellowstone, Grand Teton, and Glacier National Parks in my backyard. I am an avid skier and hiker as well as a frequent visitor to our parks and other public lands. I am passionate about ensuring these treasured landscapes are around for my children and their children to enjoy.

My testimony today will explain why creating a dedicated fund to help reduce the National Park Service’s deferred maintenance backlog is a necessary step toward meeting the agency’s mission, set out in the 1916 Organic Act, to “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”[1]

Conservation is ultimately about caring for and maintaining our lands and resources. Yet congressional annual appropriations for the National Park Service do not cover the costs to preserve the parks for present and future generations. Currently estimated at $11.6 billion, the agency’s deferred maintenance backlog impairs the public’s enjoyment of America’s park units.[2] In some cases, buildings, trails, and roads within the park system are closed due to safety concerns. Leaking wastewater systems have polluted streams in Yellowstone and Yosemite. Band-aid repairs on Grand Canyon National Park’s water distribution system have caused water shortages and facility closures. From historic buildings that need rehabilitation to failing bridges and deteriorating trails, we are losing access in the parks we love. They are in need of repair.

In my testimony today I will offer support for the Restore Our Parks Act. Addressing the deferred maintenance problem must be a priority to ensure our parks are preserved and available for enjoyment today and in the future. I will also provide a few ideas to help the agency better address its maintenance and operational shortfalls.

Background on Deferred Maintenance

In 1997, my colleague Don Leal and I researched the state of our national parks. In the resulting PERC publication, we wrote: “Our national parks are in trouble. Their roads, historic buildings, visitor facilities, and water and sewer systems are falling apart.”[3] We estimated the maintenance backlog then to be about $5.3 billion.

Now, more than 20 years later, the backlog has more than doubled. This is in part because the agency’s infrastructure is aging but also because for several decades Congress has not provided park managers with adequate, reliable funding to maintain park resources and assets. Our 1997 report explained that the operating budget of the National Park Service increased an average of 3.1 percent per year between 1980 and 1995, after adjusting for inflation. Over the same time, capital spending on major park repairs and renovations fell at an inflation-adjusted average annual rate of 1.5 percent.

The story is no better today. According to a 2017 Congressional Research Service report, the operating budget of the National Park Service increased at an average annual rate of 1.15 percent between 2007 and 2016, while the park construction budget fell at an average annual inflation-adjusted rate of 4.3 percent.[4] Over that same period, national park acreage increased by 432,000 acres as 23 new park units were added. James Ridenour, NPS director from 1989 to 1993, called this the “thinning of the blood” of the park system.[5] By stretching limited park resources across more units, the quality of the system and the ability of the agency to run it is diminished.[6] The growth and maintenance needs of our parks have outpaced available funding.

The National Park Service is struggling to keep up with its aging facilities and new acquisitions given the current resources that are available for repair and maintenance. At the end of fiscal year 2017, the deferred maintenance backlog across national parks was $11.6 billion.[7] That is an increase of $275 million from the previous year and more than four times the total annual NPS budget.

The deferred maintenance backlog refers to the total cost of all maintenance projects that were not completed on schedule and therefore have been put off or delayed. The effects of the backlog show up throughout the National Park System in the form of dilapidated visitor centers, deteriorating wastewater systems, and crumbling roads, bridges, and trails. Two-fifths of all paved roads in national parks are rated in “fair” or “poor condition.” Dozens of bridges are considered “structurally deficient” and in need of rehabilitation or reconstruction.[8] And thousands of miles of trails are in “poor” or “seriously deficient” condition.[9] More than half of the backlog is transportation-related assets.

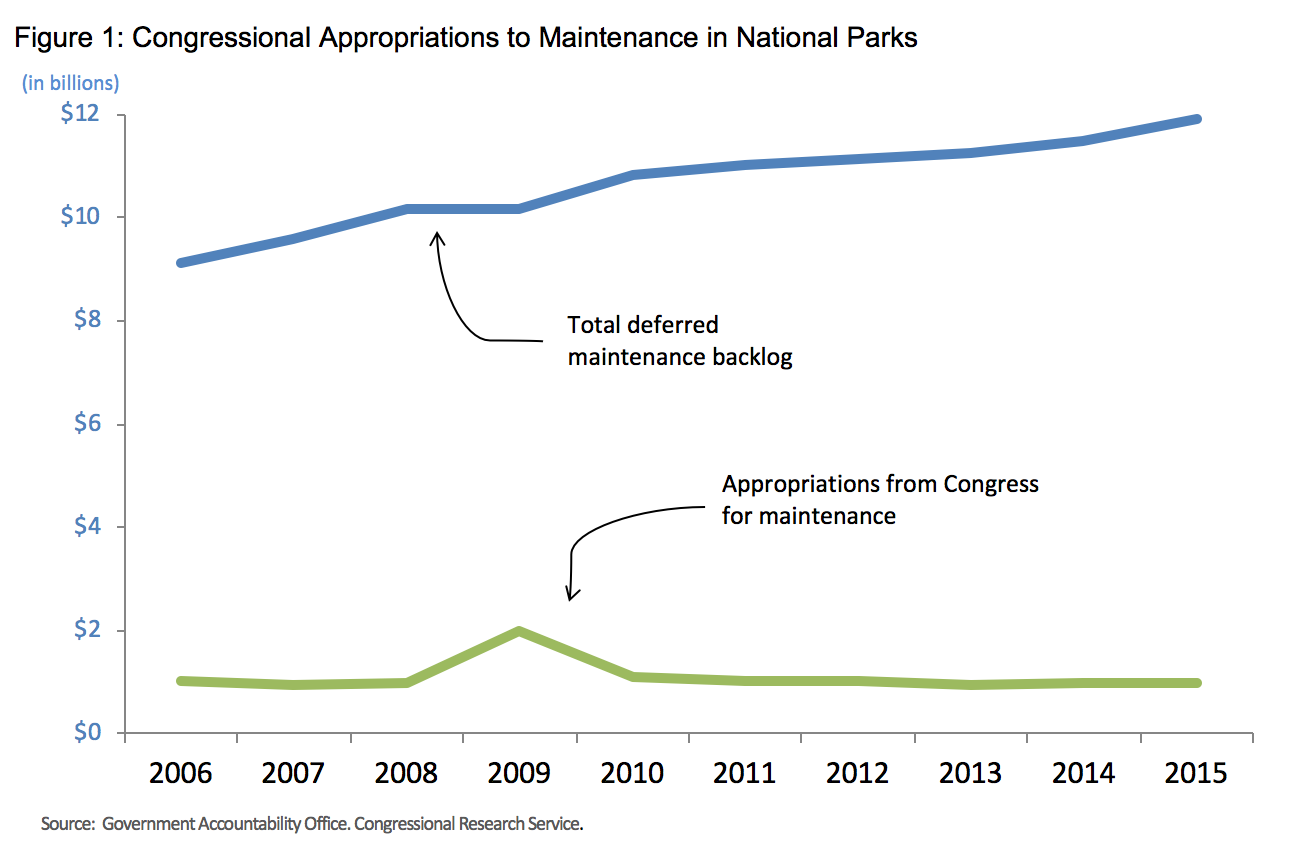

Although congressional appropriations make up the vast majority of deferred maintenance funding, Congress is unlikely to solve the problem through annual budgetary appropriations alone. Something more secure and reliable is needed. Only a fraction of NPS annual appropriations are spent on deferred maintenance. A recent report by PERC found that from 2004 to 2014, Congress appropriated an average of $521 million each year to projects related to deferred maintenance, or approximately 4 percent of the agency’s total backlog (see Figure 1).[10] The agency has estimated that it would have to spend $700 million per year on deferred maintenance just to keep the backlog from growing.[11]

If conservation is about taking care of what you own, the maintenance backlog is a reminder that we are not being good stewards of our public lands. At its core, addressing the maintenance issue is about ensuring families and visitors enjoy their experiences in the national parks, a fundamental principle of the Organic Act. To ensure our national parks are preserved and accessible in the future we must take care of what we have in a timely fashion by prioritizing the care and maintenance of existing parks.

Restore Our Parks Act

The Restore Our Parks Act would establish the National Park Service Legacy Restoration Fund, which would serve as a mandatory fund dedicated to addressing the NPS deferred maintenance backlog. The fund would be comprised of a portion of revenues from energy development, including oil, gas, coal, alternatives, and renewables from federal land or water that would otherwise go into the U.S. Treasury. Half of these energy development revenues that are not already obligated for other purposes would be deposited into the fund each year for five years, from 2019 to 2023, with an annual cap of $1.3 billion. Unspent monies can be retained in the fund into perpetuity. Private donors could also donate additional amounts to enhance the fund.

Under the proposed legislation, the NPS director would allocate money from the National Park Service Legacy Restoration Fund for high-priority deferred maintenance needs to repair and rehabilitate park assets and transportation-related projects. Any portion of the fund determined by the secretary of the interior to be in excess of current deferred maintenance needs could be invested. The secretary of the Treasury would invest the funds in a public debt security with maturity suitable to the agency’s needs. Interest earned would be a part of the Legacy Restoration Fund and available for spending on deferred maintenance projects. Monies in the fund would be available for NPS expenditure without further appropriation or time limitation.

The National Park Service Legacy Restoration Fund would provide both short- and long-term benefits. High-priority deferred maintenance projects ready to be immediately addressed could be funded using the Legacy Restoration Fund. Longer-term needs could also be addressed using interest earned from investing a portion of the energy development revenues that would otherwise be deposited into the fund. Similar to an endowment, interest earned from the invested funds could be used for deferred maintenance projects, and the principal would remain invested.

The NPS Legacy Restoration Fund is important because, unlike other funds such as the Land and Water Conservation Fund, it is a dedicated fund that does not require annual congressional appropriations or approvals. Furthermore, the Restore Our Parks Act gives the NPS director the authority and flexibility to allocate the revenues to high-priority deferred maintenance needs. By allowing a portion of the fund to be invested, the act can balance present deferred maintenance needs with expected future needs.

The Restore Our Parks Act can help address the growing deferred maintenance problem better than existing tools for a number of reasons:

- The act provides a consistent and reliable dedicated fund that is available for park service use “without further appropriation or fiscal year limitation.” Historical reliance on annual appropriations to tackle deferred maintenance issues is less reliable because appropriated budgets vary annually according to political interests and typically have a time spending limit.

- The National Park Service has prioritized deferred maintenance projects system wide and can allocate from this fund accordingly without political input. By granting the agency flexibility to determine how the Legacy Restoration Fund is allocated toward deferred maintenance needs, the act would help accomplish Interior Secretary Zinke’s priority to place more decision-making authority in the hands of local officials who better understand the needs on the ground, rather than Congress.

- The act creates a quasi-endowment fund by allowing the interior secretary to invest a portion of the energy development revenues and depositing income earned back into the fund. This can enhance both the longevity of the fund and the resources available for future deferred maintenance projects.

- Because the fund has no fiscal year limitation and deposits can be invested, an endowment fund could be created where the principal remains invested and the income on investment provides a continuous source of reliable funding for maintenance needs.

- The fund is dedicated to deferred maintenance and cannot be used for land acquisition, which can add to the maintenance problem.

- The fund will not replace discretionary funding. Historically, it has often been the case that new NPS funding sources are matched by a reduction in appropriations. This fund is designed to provide additional total revenues for the National Park Service.

The Importance of Routine Maintenance

Deferred maintenance is simply the result of not performing routine maintenance. When routine maintenance is not completed, facilities can deteriorate three to five times faster than if they were properly maintained.[12] Replacing or repairing a roof in a timely fashion, for example, can prevent more costly repairs that result from a leak. Yet, too often, routine maintenance is not a funding priority in the parks.

To park visitors, the benefits of routine maintenance are largely unseen as such work slows deterioration but does not add new facilities or services. Hence, routine maintenance is less politically appealing than creating new parks and facilities, or even than funding the more high-profile deferred maintenance problems that have captured headlines in recent years.

Although the Restore Our Parks Act would help address the existing backlog and provide an endowment-like funding source for future deferred maintenance projects, the act does not address the underlying challenge, which is inadequate funding for routine (or cyclic) maintenance projects. The majority of routine maintenance is now funded through base appropriations. Yet, as discussed above, appropriations are not sufficient to cover routine maintenance needs, as demonstrated by the growing deferred maintenance backlog. Furthermore, if deferred maintenance funding is the only way to address critical needs, park managers may be left with no other choice but to forgo routine upkeep, which contributes to more deferred maintenance in the future and comes at a higher total cost to taxpayers than investing it ongoing, cyclic maintenance.

Addressing the Routine Maintenance Problem

The Restore Our Parks Act could address the routine maintenance issue by creating an endowment for cyclic maintenance. As it is designed, the secretary of interior can request that a portion of energy development revenues are invested. Rather than treat these like a savings account, where securities have a maturity at which time all invested funds are returned to the Legacy Restoration Fund, the invested funds could be treated as an endowment. An endowment would keep principal invested, allowing the income earned to be returned for park use. This could provide a reliable funding source for both routine and deferred maintenance needs.

The Federal Lands Recreation and Enhancement Act (FLREA) allows 80 percent of a given park’s user-fee revenues to be retained and spent within that park without further appropriation. In 2016, national parks generated approximately $199 million in fee revenues collected under FLREA. That total is expected to rise by $60 million annually after the modest fee increases that took place in June 2018.[13] According to internal NPS policy, about 55 percent of FLREA revenues must be spent on deferred maintenance. The use of fee revenues may nominally reduce the deferred maintenance backlog, but by disallowing spending on routine maintenance, it likely worsens the future backlog. Park policy should be more flexible to allow managers to use the fees as they see best fit for each park. In particular, managers should be allowed to balance cyclic and deferred maintenance needs.

Nevertheless, FLREA is an important part of park budgets. Though there are some restrictions on use, these park revenues do not need to be appropriated by Congress. Retaining fees onsite encourages managers to collect fees and to invest in areas that, within the NPS policy limitations, will best protect park resources and enhance visitor quality. FLREA is set to expire September 30, 2019. It should be made permanent with fewer spending restrictions.

The Legacy Restoration Fund is a great start to help alleviate the deferred maintenance problem by providing resources to tackle existing deferred maintenance issues. Next steps need to include addressing the core problem of inadequate routine maintenance in the parks. Considering a balance of deferred and cyclic maintenance in the Restore Our Parks Act is one method to get there. Giving park managers greater autonomy and extending FLREA to provide a reliable future revenue source would also help reduce the burden.

Conclusion

The deferred maintenance backlog in our national parks is a major problem that is crippling the ability of the National Park Service to achieve its mission. Congressional appropriations have proven inadequate and too unreliable to resolve the problem. The Restore Our Parks Act can help reduce the current backlog. By establishing a dedicated fund, the act would provide a relatively secure and dependable source of revenues for park maintenance that is separate from the annual congressional appropriations process. But in order to fully solve the backlog we need to not only tackle deferred maintenance but also ensure that today’s routine maintenance needs do not become tomorrow’s deferred maintenance backlog.

It will take multiple creative approaches to adequately conserve and maintain our national parks for future generations, but the Restore Our Parks Act is a step in the right direction to enhance park stewardship.

Video of Holly Fretwell’s testimony is available here.

Notes

[1] 16 U.S.C. I.

[2] National Park Service, “Planning, Design, and Construction Management,” NPS Deferred Maintenance Report for FY2017. Available at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/defermain.htm.

[3] Donald Leal and Holly Fretwell, “Back to the Future to Save Our Parks,” PERC Policy Series, (1997). Available at https://www.perc.org/1997/06/01/back-to-the-future-to-save-our-parks/.

[4] Laura B. Comay, “National Park Service: FY2017 Appropriations and Ten-Year Trends,” Congressional Research Service Report R42757, (March 14, 2017). Available at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42757.pdf; Property and Environment Research Center, “A New Landscape: 8 Ideas for the Interior Department,” PERC Public Lands Report, (March 9, 2017). Available at https://www.perc.org/articles/new-landscape.

[5] James Ridenour, “The National Parks Compromised: Pork Barrel Politics and America’s Treasures,” Ics Books, Merrillville, Indiana, (1994).

[6] Kurt Repanshek, “Decommissioning National Parks: Some History and Some Ominous Clouds,” National Parks Traveler, (March 27, 2008). Available at https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2008/03/decommissioning-national-parks-another-look.

[7] National Park Service, “Planning, Design, and Construction Management,” NPS Deferred Maintenance Report for FY2017. Available at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/defermain.htm.

[8] Federal Highway Administration, “2015 Status of the Nation’s Highways, Bridges, and Transit: Conditions & Performance,” Transportation Serving Federal and Tribal Lands. Available at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/2015cpr/es.cfm#12.

[9] National Park Service, “Restoring National Park Trails,” Trail Conditions. Available at https://www.nps.gov/transportation/activities_trails.html.

[10] See Property and Environment Research Center, “Breaking the Backlog: 7 Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred Maintenance Problem,” PERC Public Lands Report, (February 2016). Determining the exact amount of funding allocated to deferred maintenance each year is difficult because funding comes from a variety of budget sources, each of which are also used to fund other activities as well. Moreover, the NPS does not report the total funding allocated to deferred maintenance each year. Figure 1 reports GAO data on the annual amounts allocated for all NPS maintenance, including deferred, cyclic, and other day-to-day maintenance, which averaged $1.2 billion per year between 2006 and 2015. See GAO, “National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve Efforts,” GAO-17-136, (December 13, 2016). Available at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-136.

[11] “Statement of Jonathan B. Jarvis, Director, National Park Service, Before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, for an Oversight Hearing to Consider Supplemental Funding Options to Support the National Park Service’s Efforts to Address Deferred Maintenance and Operational Needs,” (Testimony of Jonathan B. Jarvis). (July 25, 2013). Available at https://www.energy.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/files/serve?File_id=6D4ED073-B1F5-42CF-A61A-122BE71E67B9.

[12] National Park Service, “Deferred Maintenance Backlog,” Park Facility Management Division, (September 24, 2014). Available at http://www.nps.gov/transportation/pdfs/DeferredMaintenancePaper.pdf.

[13] National Park Service, “National Park Service Announces Plan to Address Infrastructure Needs & Improve Visitor Experience,” (April 12, 2018). Available at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/04-12-2018-entrance-fees.htm.