In recent years, there has been increased attention on so-called “conflict minerals” and whether trade in them has fueled civil wars and violence. The minerals are essential components of mobile phones, tablets, and similar electronic devices, and the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is a principal source of them.

Amidst growing concern, Congress passed legislation in 2010 that aimed to ensure purchases of such minerals were not funding armed groups. The measures were introduced as Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act and required companies to disclose the source of their purchases of tin, tungsten, and tantalum—the primary minerals in question. The measure aimed, to quote co–sponsor U.S. Rep. Barney Frank, to “cut off funding to people who kill people.”

Human rights advocacy groups supported the bill as a positive step. The logic was that minerals in the DRC were mined under the control of illicit armed militias who brutalized locals, and purchases from these sources fueled such violence. In response, Dodd-Frank tried to coax large companies like Apple and Intel, whose products contain the minerals, to declare their provenance. The hope was that the regulation would reduce funding to militias, thereby reducing the suffering of people in affected communities.

Now, a few years removed from the legislation taking effect, we can examine whether it achieved its aims. In two recent studies, coauthors and I examined the effects of the policy and found that while the conflict minerals measures may have reduced militia funding, this achievement came at the expense of human lives. The legislation had the unintended effect of more than doubling infant mortality in villages near eastern DRC mining sites. Moreover, it also appears to have increased militia violence against civilians, rather than curbing it.

The Dodd-Frank Act disrupted an informal arrangement that was far from perfect and replaced it with a dangerous and chaotic environment in which armed groups violently sought new sources of revenue.

These unwanted consequences were a result of two main forces. First, Section 1502 initially caused a widespread, de facto boycott on minerals from the eastern DRC. Rather than engaging in costly due diligence to identify the sources of minerals—and risking being considered a supporter of rebel violence—some U.S. companies simply stopped buying minerals from the region. This de facto boycott had the intended effect of reducing funding to militias, but its unintended effect was to undercut families who depended on mining for income and access to health care. The decreases in mineral production rocked an artisanal mining sector that had supported an estimated 785,000 miners prior to Dodd-Frank, with spillovers from their economic activity thought to affect millions.

Second, the legislation changed the relative value of controlling certain mining areas from the perspective of militias, who changed their tactics accordingly. Before the boycott, the militias could maximize revenue by taxing tin, tungsten, and tantalum at or near mining sites. They therefore had an interest in keeping mining areas productive and relatively safe for miners. After the legislation, the militias sought to make up for reduced revenue in other ways. According to the evidence, they started to loot civilians who were not necessarily involved in mining. They also started to fight for control over other commodities, including gold, which was in effect exempt from the regulation.

In short, the Dodd-Frank Act disrupted an informal arrangement that was far from perfect, yet somewhat stable, and replaced it with a dangerous and chaotic environment in which armed groups violently sought new sources of revenue. The account sheds light on the deadly, if unintended, consequences of conflict-mineral regulation and alternatives that could have potentially achieved the aim of reducing militia activity without harming local civilian populations.

Artisanal Mining Or Bust

The DRC contains large deposits of valuable minerals such as tin, tungsten, and tantalum—the so-called “3Ts.” In recent years, armed militia groups have controlled a portion of the production of 3T minerals, along with gold, in the eastern DRC by taxing and extorting miners.

The minerals are extracted by artisanal miners who worked informally and independently. These types of miners use minimal technology and a labor-intensive process that requires panning and digging for alluvial, open-pit, and hard-rock mineral deposits. In the years prior to Dodd-Frank, artisanal miners extracted an estimated 90 percent of the minerals exported from the country. Armed militias, generally composed of young men, controlled or regularly visited approximately half of such mines, usually to tax and extort miners.

Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act was signed into law on July 21, 2010. The narrow goal may have been to cut off funding to armed groups, but the broader aim seems to have been to reduce human suffering in the DRC. The act directed the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) to create disclosure rules for companies that make products containing tin, tungsten, tantalum, or gold. The rules require companies to conduct “due diligence” on the origin of the minerals in question. If minerals come from a conflict-mining zone, then the buyer must report on the possibility that militias benefited from the purchases.

While Section 1502 did not prohibit companies from purchasing minerals that originate in conflict-mining zones, many observers agree that it acted as a de facto boycott of 3T minerals. Rather than incurring the costs and effort of verifying that mineral purchases did not finance armed militias, many U.S. companies decided not to buy 3Ts from the entire conflict zone. Furthermore, in conjunction with Section 1502, the DRC government imposed a ban on artisanal mining in three eastern provinces in September 2010. The DRC lifted its ban in March 2011, but by the next month the implicit boycott of minerals from the eastern DRC had became explicit: In April 2011, the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition, a group of electronics and tech companies, stopped buying 3Ts from smelters who could not prove their source minerals did not fund conflict. It’s likely that Dodd-Frank encouraged this explicit international boycott, which effectively replaced the DRC government’s ban.

What effect did Dodd-Frank, the associated mining ban, and the explicit boycott have on mining activity? Official data reveal a substantial drop in exports of 3Ts from the conflict area after Dodd-Frank, followed by a rebound in exports over 2013-16. (Export data provide a less reliable indicator of gold production because virtually all gold mined in the eastern DRC is smuggled through unofficial channels. Production generally rose, with a slight decrease when the mining ban was in force in 2011, but overall there is little evidence that Dodd-Frank reduced gold production.)

Taken together, the data suggest that Dodd-Frank and the mining ban were effective at slowing 3T mining within the targeted conflict-mining zone but less effective at slowing gold mining. There are two main reasons why gold production rose despite its official status as a “conflict mineral” under Dodd-Frank. First, DRC gold mainly supplies jewelry markets in the Middle East and East Asia, whereas 3Ts primarily supply companies that are regulated by Dodd-Frank or members of the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition. Second, while it is technologically feasible to track the origin of 3Ts and demonstrate whether they coincide with areas controlled by armed groups, it is much more difficult to determine the providence of gold because it can be more easily smelted on site or earlier in the supply chain.

Legislation Backfires

In recent research, economists Jeremy D. Foltz, David Elsea, and I assessed the infant mortality effects of Dodd-Frank using data on births that are currently available for children born through 2012. Our first significant finding was that among all eastern DRC villages near 3T mines, average infant mortality became relatively higher in communities within the zone targeted by the conflict-mineral policies after those policies were initiated. In particular, our research suggests that this increase in infant mortality may have been caused by the de facto boycott of 3T minerals because infant mortality did not in general rise elsewhere. Furthermore, within the geographic area targeted by Dodd-Frank, we found that infant mortality became higher in villages closest to 3T mines.

The combined evidence suggests that Dodd-Frank increased the probability of infant deaths (that is, babies who died before reaching their first birthday) from 2010 to 2013 for children who lived part of or all of their first year in villages targeted by the legislation and mining ban. The most conservative estimate is that the legislation increased infant mortality from a baseline average of 60 deaths per 1,000 births to 146 deaths per 1,000 births over this period—a 143 percent increase. (By contrast, we found no evidence that Dodd-Frank affected infant mortality in villages near gold mines.)

How exactly did Dodd-Frank increase infant mortality in villages near 3T mines? One possible explanation is that the legislation reduced families’ income levels and therefore limited their ability to access important health care goods, such as disease-preventing bednets. (Our research estimated that bednet use was lower in policy-targeted villages than it would have been without the Dodd-Frank-induced boycott.) Decreases in health care consumption could have also been driven by reductions in access to or higher costs of health care in the affected villages—both of which are plausible outcomes as the transportation of goods and services into affected villages declined along with their economic importance following the mineral boycott.

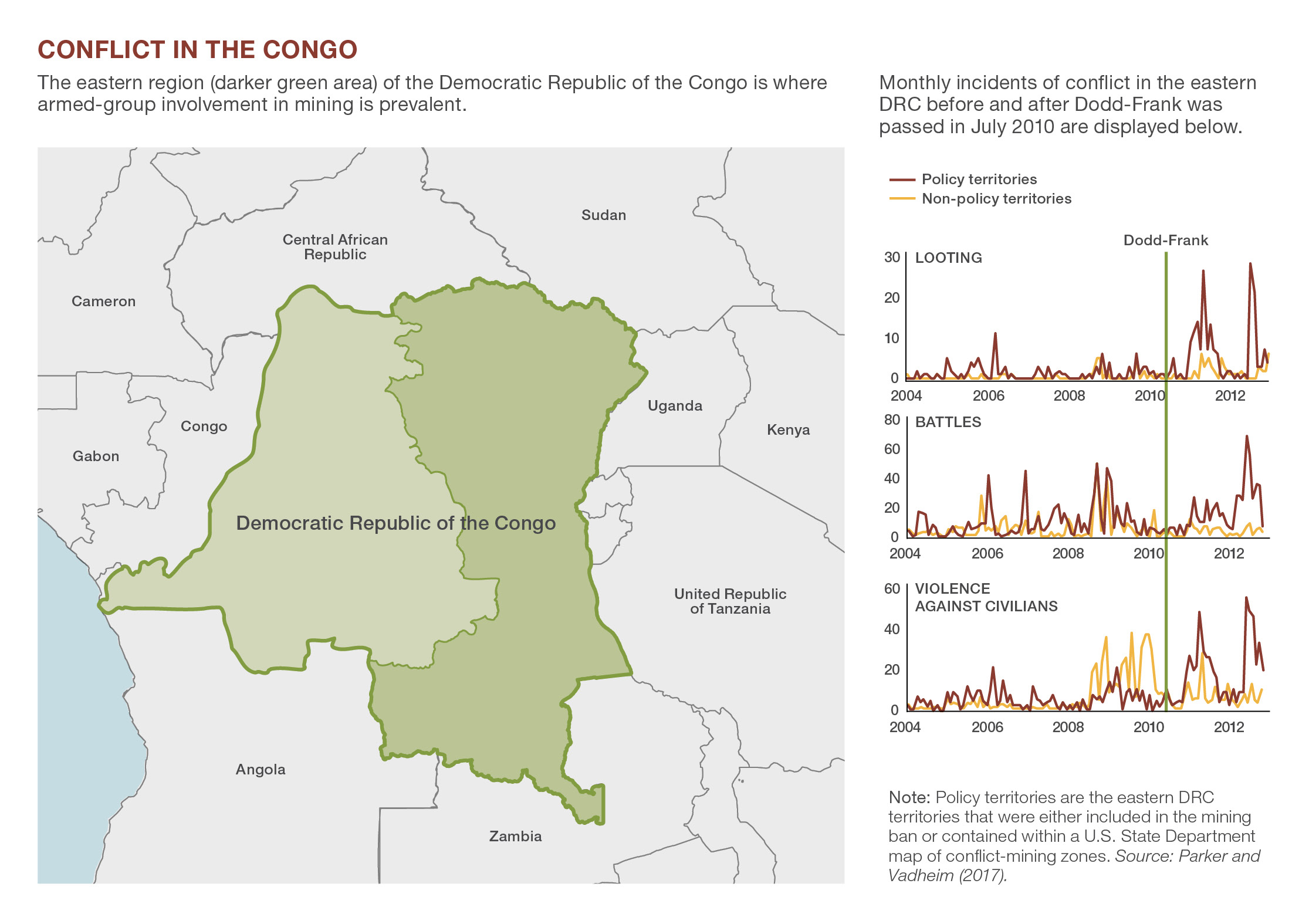

Dodd-Frank’s effect on infant mortality is one matter, but its impact on defunding militias and reducing violent conflict was the law’s primary aim. To study whether the policy successfully reduced conflict, coauthor Bryan Vadheim and I assessed the prevalence of looting, battles, and violence against civilians in the region after the legislation was passed. Our analysis revealed that Dodd-Frank and the related mining policies that followed triggered an increase in looting within the targeted territories, near mines, and even in surrounding areas not focused on mining.

At the end of 2010, after the passage of Dodd-Frank, looting in the territories targeted by the mining policies became more common and remained that way through much of 2011 and 2012, when our study period ended. There was not a commensurate rise in looting in the non-policy-targeted territories. The incidence of violence against civilians also increased in the policy regions after the legislation, but there was no commensurate rise in the non-policy regions. Our results also indicate that the probability that a policy-targeted territory would have an inter-militia battle increased with the number of gold mines in a territory after the passage of Dodd-Frank until 2012. This makes intuitive sense: Dodd-Frank would be expected to encourage battles over gold, because the policy raised its value relative to 3T minerals.

The findings are consistent with the deterioration of a “stationary bandit” equilibrium—a concept initially put forth by economist Mancur Olson in 1993. In the context of the eastern DRC, the idea is that militia groups who seek to stay in mining areas for years will not use violence to incapacitate its local mining workforce. On the contrary, such groups might invest in security and other provisions to avoid uprisings and work to keep mining areas safe and productive. This interpretation is consistent with the documented examples of some militias charging fees to enter mining sites and, in return, offering a degree of protection—even if only from themselves—as a mafia group would do.

According to our research, the top-down decision by the U.S. Congress to regulate “conflict minerals” did not reduce human suffering in the eastern DRC. Instead of reducing violence, the evidence indicates that, at least in the short term, the mining policies increased violence against civilians.

Armed groups that were stationed at 3T mines when Dodd-Frank passed had incentives to change their tactics. Rather than staying in mining areas that were on the wane, they found it more profitable to switch efforts toward looting civilians and fighting rival armed groups for the right to station at gold mining sites. At the same time, some armed groups that were formerly stationed at gold mines would have incentives to switch to looting civilians rather than engaging in battles with more powerful rival armed groups. Dodd-Frank, therefore, may have converted stationary bandits into more dangerous “roving bandits,” as Olson described them, whose anarchy and plunder destroy “the incentive to invest and produce, leaving little for either the population or the bandits.”

Do No Harm?

According to our research, the top-down decision by the U.S. Congress to regulate “conflict minerals” did not reduce human suffering in the eastern DRC. Instead of reducing violence, the evidence indicates that, at least in the short term, the mining policies increased violence against civilians. The policies also appear to have increased infant mortality, demonstrating how interventions that intend to enhance human rights can unintentionally harm the vulnerable populations they seek to protect.

Advocates of Dodd-Frank Section 1502 could argue the legislation needed more time to work, and it is possible that long-run benefits for infant health and household welfare will eventually emerge if the legislation can reduce conflict and enable mining to resume. Even if it does, it is worth asking if the short-run human costs that have already been suffered were justified. Our study examines conflict data through 2012, but an in-progress study by researchers Nik Stoop, Marijke Verpoorten, and Peter van der Windt extends the analysis through 2015, using comprehensive and updated mining data. Unfortunately, their analysis does not reveal much improvement in the situation. The authors conclude that Section 1502 does not do what it intends to do. In the longer term, battle incidents in gold mining areas remain high, suggesting that rebels continue to fight over gold sites. Moreover, the researchers detect a strong increase in riots, a sign of social upheaval. The one piece of good news is that looting of civilians appears to have decreased some in 3T mining areas.

Today, the future of Section 1502 is uncertain. In 2017, the Trump administration drafted an executive order that called for suspending Section 1502 and replacing it with a “more effective” policy, which raises questions about why the measure was flawed and what kind of policy might work better.

A better-targeted certification program could have caused less collateral damage, especially if it were offset with commensurate health care and income aid to help families near mining villages. A more precise approach, perhaps, would have been to give companies waivers for compliance until monitoring systems were in place, or to create a default rule in which minerals were considered conflict free unless proven otherwise.

At a more fundamental level, we should ask what might have happened if the money spent on Section 1502 compliance and lobbying—reportedly billions of dollars—was instead spent on alternative forms of foreign aid aimed at bolstering human rights and economic opportunities in the eastern DRC. There is a general strategy that economists might endorse: Use foreign aid to raise the opportunity cost of engaging in conflict. If foreign policy can successfully give young men in the DRC better alternatives than militia participation, then conflict might be reduced through voluntary exit out of militias or out of risky mining areas. Foreign interventions that create better opportunities in rural areas, or that reward “conflict-free minerals” rather than penalizing conflict minerals, might achieve this. At the very least, such interventions may avoid simply shifting conflict to other places or causing a boycott of a region where jobs, income, and health care are already scarce.

References:

Parker, Dominic P. and Bryan Vadheim. 2017. “Resource Cursed or Policy Cursed? US Regulation of Conflict Minerals and Violence in the Congo.” Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 4(1): 1-49.

Parker, Dominic P., Jeremy Foltz, and David Elsea. 2016. “Unintended Consequences of Sanctions for Human Rights: Conflict Minerals and Infant Mortality.” Journal of Law & Economics 59(4): 731-774.

Stoop, Nik, Marijke Verpoorten, and Peter van der Windt. 2018. “More Legislation, More Violence? The Impact of Dodd-Frank in the DRC.” Working Paper.