From Netflix’s documentary series Fire Chasers to the recent heart-wrenching stories of destruction in California, the effects of catastrophic wildfire have never been more visible. Indeed, last year’s fire season was the most costly on record and trailed only 2015 for the most acres burned in a single year.

These costs have taken a toll on federal budgets devoted to managing forests on public lands. Today, more than half of the U.S. Forest Service’s budget is spent fighting fires. That leaves limited funding for much-needed restoration projects such as fuel-reduction treatments and prescribed burns that could enhance forest resiliency, mitigate fire risk, and protect water supplies and air quality. Earlier this year, Congress passed important wildfire funding reforms that will free up more public dollars for such projects, but the Forest Service’s backlog of restoration work could take decades to work through—and that is time our national forests and surrounding communities do not have.

Recognizing the immediacy of the challenge and enormity of the workload, the Forest Service has begun to develop creative partnerships with public water utilities and private water-dependent companies to chip away at the problem. For example, the agency has established recent partnerships with Denver Water and Coca-Cola to help fund watershed restoration projects that reduce fire risk and also protect important water resources. By supporting such restoration projects, utilities and private companies can protect water resources, avoid costly sedimentation events, and safeguard infrastructure. These partnerships aren’t philanthropy; they are private investment decisions by informed market participants who understand the risks—and potential costs—posed by wildfire.

These creative partnerships aren’t philanthropy; they are private investment decisions by informed market participants who understand the risks—and potential costs—posed by wildfire.

It’s one thing for water users to fund restoration projects in their own watersheds where they’ll see direct benefits. But we believe there’s an opportunity for private investors—such as pension plans, insurance companies, or family offices—seeking financial returns to make even more of these restoration projects possible.

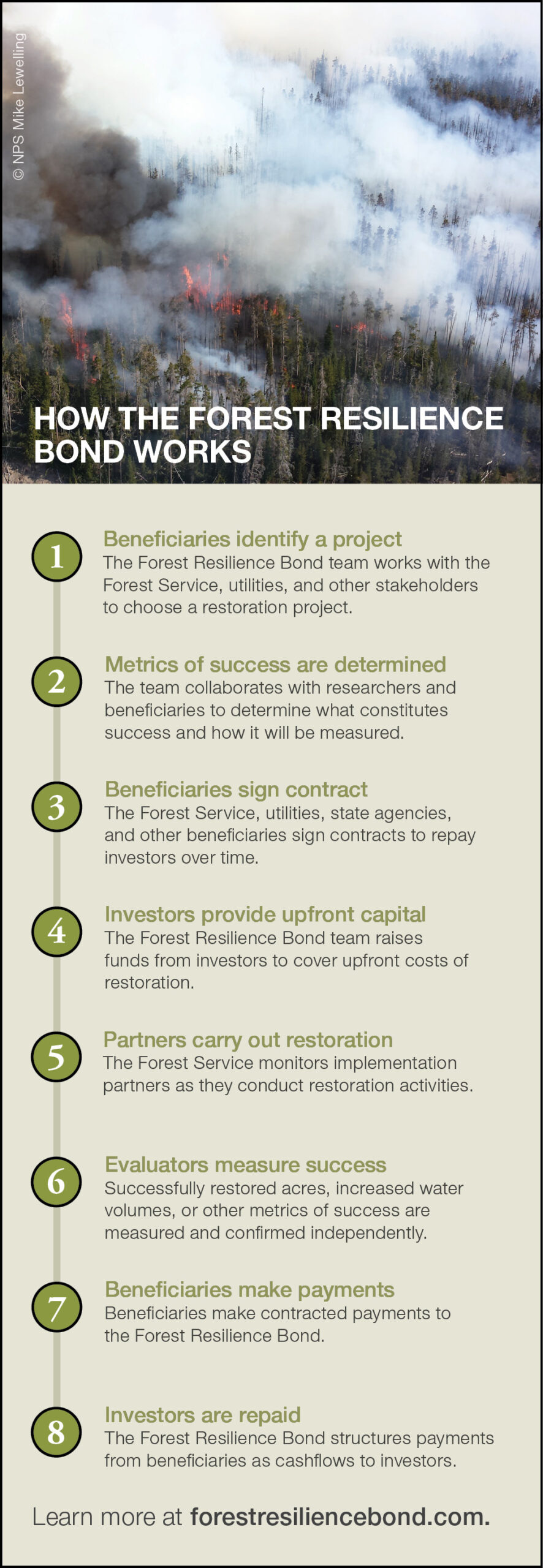

One new tool the Forest Service is exploring is called a Forest Resilience Bond, a public-private partnership developed by Blue Forest Conservation, the World Resources Institute, and Encourage Capital that allows private capital to cover the upfront costs of forest restoration projects on public lands. The investment provides a market-rate return to investors by allowing beneficiaries, such as water and electric utilities, water-dependent companies, state agencies, and even the Forest Service, to share the costs and potential benefits of restoration projects. The Forest Resilience Bond team will launch the first pilot project in the Tahoe National Forest later this year, with participation from the Forest Service, the Yuba County Water Agency, and various California state agencies.

The Forest Resilience Bond works as follows: Once a potential restoration project is identified, Blue Forest Conservation and its partners work with beneficiaries to understand their priorities and develop cost-share or performance-based contracts to reimburse the costs of the project over time. Various investors, such as pension funds and endowments, then provide capital for the upfront costs of the restoration project, which is passed on to a project manager that completes the restoration projects as planned and approved by the Forest Service. After the work is completed, the beneficiaries make their contracted payments, and investors are repaid over a 10-year period.

This investment model has several advantages over the status quo of using scarce public dollars to fund most forest restoration projects on public lands. By allowing utilities and water companies to opt into these investments and creating pay-for-performance contracts, these risk-averse stakeholders can pay for benefits as they receive them instead of in advance, which decreases risk and increases the likelihood of their participation. In addition, we help provide financing so that smaller entities that don’t operate at the scale of Denver Water or Coca-Cola can participate. The proposition of outside financing can also serve as a powerful motivator to bring stakeholders together.

By making investments in our public lands a financially sustainable proposition, long-term investors such as pension funds, endowments, and insurance companies can diversify their portfolios while also better serving the social and environmental well-being of their communities. And by tapping into private capital, the Forest Service could fund restoration projects at a much larger scale than would be possible if it relied solely on annual appropriations from Congress.

With the risk of wildfire and other natural disasters growing by the day, now is the time to build on these scientific advances to create new financing techniques and develop new markets. Financial tools that encourage investments in environmental quality can help preserve public dollars and protect communities while providing stakeholders and investors with the partnership opportunities they are both already demanding.The Forest Resilience Bond is just one example of a recent financial innovation that could yield conservation benefits. The widely acclaimed DC Water bond helped pilot a new public-private model to finance green infrastructure, such as permeable pavement and drainage systems that rely on vegetation to soak up runoff. These investments could save the utility billions of dollars’ worth of grey infrastructure as part of a long-term plan to control stormwater. This pay-for-performance financing helped shift risk from the utility to investors, including Calvert Impact Capital and Goldman Sachs. The pilot project has generated substantial interest in green infrastructure investment opportunities.

It is no surprise that innovations in finance have closely followed innovations in science. The ability to understand and accurately quantify outcomes from conservation and restoration activities has never been more promising. Further, the ability to assign value to these outcomes has gained wide acceptance and already become an important part of the decision-making process for natural resource managers at many utilities.