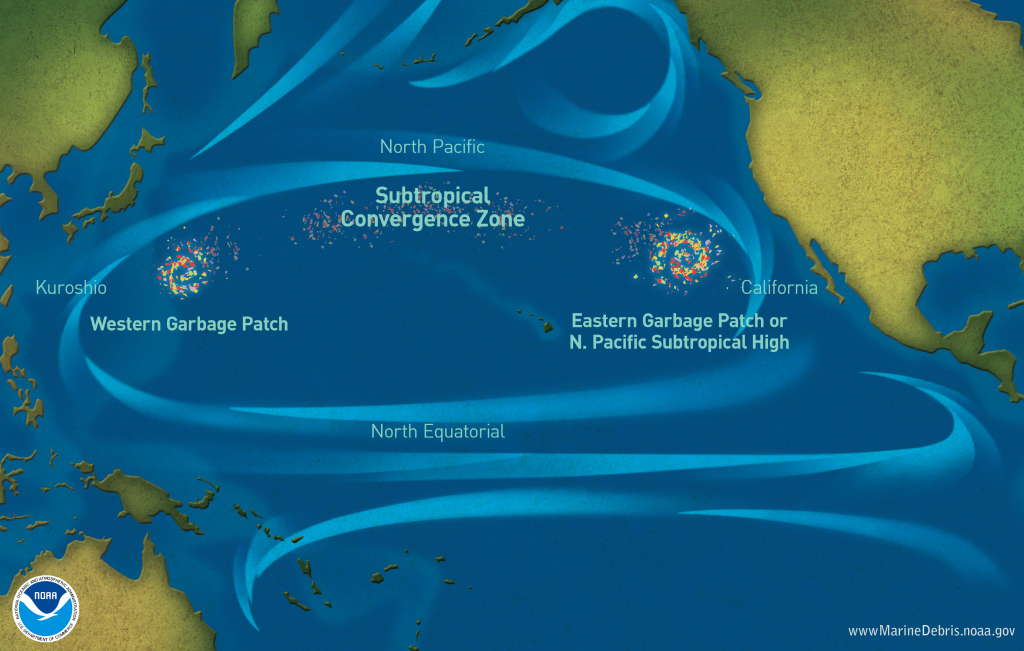

The ocean is a global commons. It’s owned by no one, controlled by no one, and open to all. Predictably, the ocean experiences the same fate as any other commons: because no one owns it or can capture the benefits of protecting it, it can be overused or polluted. This has led to overfishing. It has also caused trash to build up in remote currents like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

There are two standard solutions to commons problems: regulation or privatization. For fisheries, for instance, overuse can be mitigated by limiting the fishing season or by establishing property rights in the fishery. The former doesn’t address the underlying incentive problem, often leading to fishermen finding ways to increase their harvest within regulatory constraints thereby undermining their effectiveness. Property rights, on the other hand, align fishermen’s incentives with the health of the fishery, promising greater long-term stability.

A property rights solution to the garbage patch is difficult, so most proposals to address it focus on regulation. But there are other alternatives. The nonprofit Ocean Cleanup Project proposes to clean up the world’s ocean through breakthrough technology. They’ve developed a device that uses the ocean’s current to passively collect plastic and other debris, while avoiding impacts to marine life.

Developing and implementing the technology is expensive. So how can a project like this exist in the commons? The project is a reminder that commons present a difficult collective action problem, but not an insurmountable one. In fact, technology and human prosperity make such problems more solvable.

Although there is always some incentive to freeride when non-contributors cannot be excluded from the benefits of collective action, people nonetheless will contribute if they place a high value on ensuring those benefits arise, the benefits greatly exceed the costs, or there are reputational benefits to contributing. The Ocean Cleanup Project is relying on all three.

As people get wealthier, the value they assign to the environment increases. Until relatively recently, the ocean was treated as a convenient repository for garbage because any consequences were too small, remote, or unobservable. The consequences can still be seen in glass beaches around the world, formed by waves pummeling the coast with trash.

Today, prosperity and technologies have expanded our knowledge of the world, making people more sensitive to environmental impacts—and willing to pay to avoid them. This can be seen best through the concept of “existence value”: the value people put on knowing that some distant environmental amenity—a clean ocean, a lion on the Serengeti, or an ecosystem in the great plains—exists, even if they may never see it. Such values are contingent on human prosperity, only arising once people’s basic needs are met and increasing as people grow wealthier.

The Ocean Cleanup Project benefits from the increasing value people place on a cleaner ocean. And its long term success will depend not only on its technology working but also its ability to harness that value. Currently, it does so by raising contributions from those who place a high value on the environment.

But the greatest potential may be in the plastic that the project is removing from the ocean. Although it cannot capture the benefit of the public good being provided—a cleaner ocean—it is literally capturing another form of property in the plastics it removes. Ultimately, the project plans to recycle this material into branded products that it can sell to consumers willing to pay a little more for the knowledge that their purchase helped to clean up the ocean. If the project gets to that stage, it will join a long line of ventures that have used markets and rising prosperity to achieve previously unattainable environmental outcomes.